Federal fisheries officers descended in force to raid a sustainable seafood company in Vancouver Friday afternoon, seizing the catch of an Indigenous fish harvester and alleging it was illegally caught.

But enforcement officers are taking an unnecessary and heavy-handed approach to what seems to be a bureaucratic error caused at least in part by the Department of Fisheries’ (DFO) own licensing branch, said Sonia Strobel, CEO of Skipper Otto community-supported fishery.

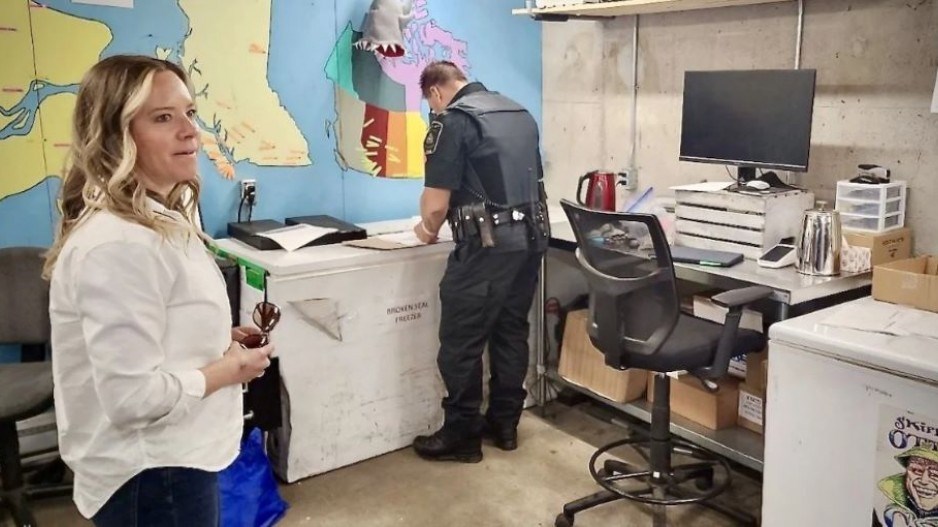

“They’re rifling through all our paperwork right now,” Strobel told Canada’s National Observer over the phone before noon.

“We’ve provided all the documents they asked for. Now they are looking through files that aren’t in any way related to the case.”

The tumult appears to be because a harvester from the Namgis First Nation was issued his community Indigenous fishing licence (PICFI) late due to a backlog and a delay in processing related to the recent public service strike from April 19 to May 3, Strobel said.

DFO and the Ministry of Fisheries did not respond to requests for comment before Canada’s National Observer’s publishing deadline.

The harvester, who’s been fishing and working with the company for years without problems, reportedly went fishing from April 28 and 29 after his licence request was submitted four days earlier and completing payments and other necessary bureaucratic tasks, Strobel said.

Typically, the licensing branch turns licensing requests around in a matter of hours, and if it takes longer than two days, typically contact the fish harvester or community licence holder, Strobel said, adding that never happened as far as she’s aware.

The harvester hit the water with the impression all was well, especially since he was issued a validation number by the DFO [contractor] to start fishing, something that shouldn’t occur if a licence hasn’t been issued, Strobel said.

“The harvester was under the reasonable impression that everything had been done,” she said.

“If he’d wanted to poach fish, why would he have followed every other condition of licence, run his [onboard] cameras, hail in and out [of port wtih DFO's contractor], and pay all this money to have it validated?”

It wasn’t until May 5, when a DFO enforcement officer called the company to hold the fish for seizure that Skipper Otto became aware there was an issue, Strobel said, adding the company isn’t responsible for verifying a licence before purchasing a catch.

After a series of phone calls and emails between Skipper Otto, the Namgis office and DFO conservation staff, it seemed clear the licence delay was simply a hold-up due to the strike and that both the DFO conservation and licensing units had been in communication the day before about the issue, Strobel said. When the company called the fish harvester, it was also news to him there was a licensing issue.

By the end of the same day, DFO had issued the outstanding licence for the fish harvester, but rather than retroactively using the application date, it is dated May 5, Strobel said.

Canada’s National Observer has confirmed the details outlined above with the fish harvester and the Namgis licensing department.

Strobel, her staff and the department managing the Namgis Nation’s licences have been repeatedly reaching out to the DFO conservation unit, lead enforcement officer and the Fisheries Ministry to get the issue resolved without success ever since, she said.

“I can't tell you how many hours I've spent. I've called everyone in DFO,” she said, adding she’s talked to the federal Fisheries Minister Joyce Murray’s office and even reached out to the director general of the Pacific region.

“I’m trying to get this result, and no one's returning my calls.”

Two teams of armed officers in bulletproof vests arrived in numerous marked vehicles and with warrants to search her business and at the cold storage company she works with in Surrey, she said.

“It clearly is an administrative error, but [enforcement] is holding the line that the date on the licence doesn’t match the date the fish were caught — therefore, it’s illegal,” she said, adding officers on scene wouldn’t give her any additional information.

Instead of being resolved with communication between all the parties, DFO has opted to launch a stressful, lengthy and costly investigation, particularly for taxpayers who will ultimately foot the bill, she said.

“The officers have seized about $20,000 in fish,” she added.

“It feels quite intimidating… particularly for our younger staff and our business partner,” Strobel said.

“They're saying that I'm under investigation because I purchased this fish from the fishermen who got it illegally,” she added.

“Therefore, I committed a criminal act by purchasing illegally caught fish.”

A situation that could have been resolved with some communication and might have merited perhaps a fine at most has escalated out of control, Strobel said.

“It’s disproportionately heavy-handed, particularly because it involves a small-scale independent Indigenous harvester.”