Vancouver’s residential real estate commands high prices. In contrast, low house prices in most U.S. sunbelt markets are bargains today for many snowbird Canadians. It’s all a question of market-based demand and supply.

Or is it?

Not really. Few if any housing markets worldwide are purely market-based. Most involve some level of government subsidies. In B.C.’s key markets, these subsidies affect the demand for the province’s wood products.

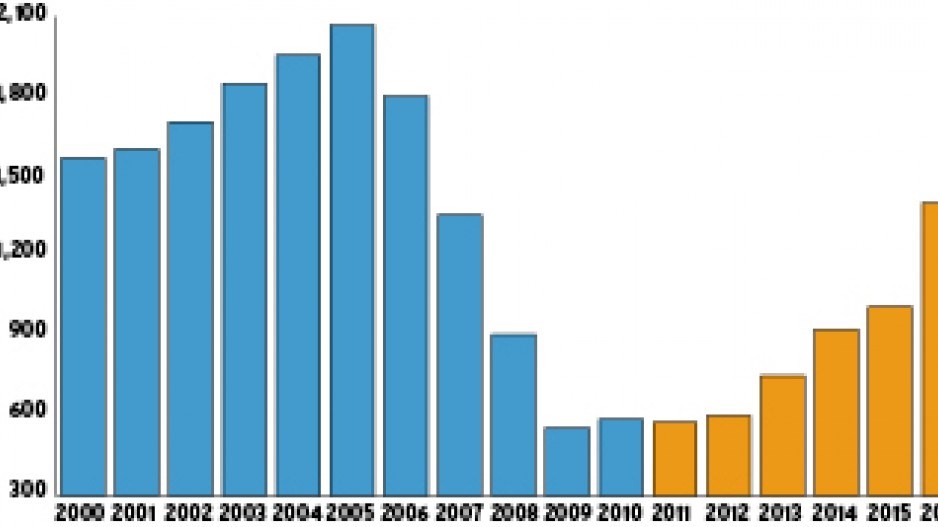

Until recently, B.C.’s lumber industry has used the bellwether of a single dominant indicator of demand – U.S. housing starts. When U.S. residential construction activity was peaking in 2005 – with starts reaching over two million units – B.C.’s wood products industry enjoyed unprecedented boom times.

Today, U.S. housing demand is a fraction of its peak levels, and the outlook is highly uncertain. There’s still a tendency to look at past patterns as a guide to the future.

But little thought has been given to how U.S. housing demand is created. More specifically, how much of the recent demand has been real versus the artificially stimulated variety?

Economists go to great pains to stress something many had forgotten during boom times. Demand is not just a reflection of need and the willingness to buy. It also requires the ability to pay.

The U.S. sub-prime crisis came as a shock. It exposed the extent to which demand for housing in the U.S. has been artificially leveraged through creative financing. The ability to pay, in many instances, was fictional.

It’s a well-known story.

The U.S. mortgage industry, and many other players in the financial system, collaborated with homebuilders to stimulate demand for home ownership. The result was to switch many households away from rental housing and low-income ownership units into housing they couldn’t afford.

In addition, many existing homeowners refinanced – at generous short-term borrowing rates. They used the money to move, upgrade or simply enjoy a better lifestyle.

There was an unprecedented boom in mortgage lending running up to the U.S. housing boom and subsequent bust. Lending standards deteriorated. In the aftermath of the housing bust, the American Dream of owning a home came crashing down.

Fast forward to today. The Dodd-Frank Act has led to the most substantial reform of the U.S. financial regulatory system since the Great Depression. Its teeth have yet to be tested. Even if it is effective, U.S. housing demand will continue to depend heavily on government subsidies.

A recent report by the IMF presents a revealing picture of U.S. tax and financial incentives for housing (www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=25156.0).

Importantly, the IMF’s analysis concludes that “the United States has the most comprehensive government intervention among advanced economies in housing finance.” That’s politically correct language for saying that the U.S. subsidizes its housing sector more than any other country in the developed world!

Tax subsidies available in the U.S. include mortgage interest deduction, which Canada doesn’t have, and which was phased out many years ago in most other countries – notably the U.K., Australia, Japan and Germany.

Other tax-based subsidies in the U.S. include property tax deductions and capital gains exclusions (which most countries have, to varying levels).

On the housing finance side, governments in many countries – including Canada, mostly via Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. (CMHC) – provide mortgage insurance. In the U.S., however, financing guarantees are backstopped by an elaborate system of subsidies including government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). Those practices and institutions are now under the housing finance-reform microscope.

Housing subsidies involve a huge cost to the taxpayer. The U.S. Treasury estimates that tax expenditures on housing – already around US$230 billion for the current fiscal year – could rise to over $330 billion by 2016. That’s a lot of revenue foregone by the U.S. government.

Ironically, despite these generous stimulus measures, the IMF concludes that many of the U.S. tax-based subsidies result in only marginal growth in the homeownership rate – the central policy objective and justification given for market intervention.

Reform is in the air.

The Obama administration is downplaying, for now, calls for elimination of mortgage interest deduction in U.S. ownership housing. Already bleeding and on its knees, it is widely held that this isn’t the time to hit the American housing industry yet again.

With the “ability to pay” of many Americans being severely compromised, what is the outlook for new housing demand in the U.S.? With greater regulation of the mortgage finance industry and the prospect of some housing subsidies being eliminated, are the best years behind the U.S. homebuilding sector?

More specific to B.C., what do these changes imply for the province’s major export market?

Frankly, it’s too early to tell with any certainty.

Longer-term demographics point to substantial levels of “pent-up” demand for new housing in the U.S. Of course, without the ability to pay in some cases, it’s not altogether real demand. That situation will require sustainable rises in household incomes.

Unfortunately, the job outlook in the U.S. is not immediately promising. A huge inventory of foreclosed homes overhangs the market. Credit markets are still dysfunctional. Overall, a full recovery in U.S. homebuilding seems a long way off.

One view of the U.S. housing-starts outlook is presented in the accompanying chart. It reflects the broadly held opinion that new residential construction activity in the U.S. might not recover to the one-million-starts level until around 2015.

There is upside to this forecast. But with the overall process of de-leveraging and an uncertain taxation and financing policy environment for housing, the upside prospects are not encouraging.

Does this constrained outlook for housing recovery in the U.S. spell trouble for B.C.’s wood products industry?

Most analysts don’t think so. Two factors make it different this time. New demand for B.C.’s wood products has emerged from China and other parts of Asia. So far, this hasn’t been enough to compensate fully for today’s depressed U.S. housing market. But as U.S. demand picks up, as it will, aggregate global demand starts to look very good for B.C.’s wood products.

In addition, many people in the B.C. lumber industry believe that this business cycle – peaking perhaps around 2015 – will be supply constrained. Mill closures have eliminated significant levels of production. Increasingly, too, sawlogs are harder to get. In part, blame the pine beetle for that.

The outlook is good for lumber profits. It’s also good, in the medium term, for house prices in most housing markets – in part because replacement costs are rising.

Speculative investments aside, regulatory changes in the U.S., along with a reduction in U.S. subsidies on housing, will help redefine future housing demand in terms of fundamentals rather than artificially stimulated and unsustainable demand.

The importance of the U.S. homebuilding industry to the overall economy, and U.S. households’ need for rental and ownership housing, suggest that public policy could be slow to remove the extensive subsidies that exist in the United States.

Vancouver’s housing market continues to benefit from in-migration from other provinces, immigration and non-resident investment inflows. Unlike the U.S. system, Canadian mortgage lenders, and suppliers of construction finance, tend not to over-stimulate housing demand and supply.

It may be tempting sometimes for Canadians to feel smug about Canada’s more stable housing-finance system versus the U.S.

But B.C.’s economy, and our personal incomes, are tied closely to construction activity in the United States. Whatever happens to new housing and home improvement in the U.S. affects us here too.

Despite the IMF’s conclusion about the ineffectiveness of U.S. housing subsidies, a rapid transition to market-based supply and demand in U.S. housing would affect wood products demand adversely.

It may bring impacts for which B.C.’s wood product manufacturers have not bargained. Perhaps better, in this case, to hope for slow and gradual shifts in U.S. housing finance – rather than rapid reforms. •