Northern B.C. doesn’t need new gas plants, pipelines and mines – it needs young people.

While Metro Vancouver business leaders continue to focus on the so-called boom in the north, a conversation is underway in the northern half of this province about a challenge that threatens the very existence of communities in this region, not just their ability to respond to multibillion-dollar investments: where are all the young people?

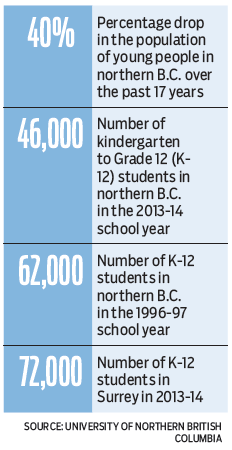

In its 2014 annual report, the University of Northern British Columbia (UNBC) highlighted an under-reported statistic: the population of young people in this region has declined more than 40% in the past 17 years.

According to the report, the total head count of kindergarten to Grade 12 (K-12) students in northern B.C. in the 2013-14 school year was approximately 46,000, compared with more than 62,000 in 1996-97. Compare that with Surrey, which had 72,000 K-12 students in 2013-14. Last year, there were slightly more than 5,000 Grade 12 students in the region, but only 3,378 in kindergarten, 3,339 in Grade 1 and 3,171 in Grade 2.

That doesn’t bode well for university enrolment a decade from now, as UNBC well knows.

And when you consider that UNBC now produces more graduates for northern B.C. than all of the other universities in the province combined, it’s unlikely the University of British Columbia, Simon Fraser University and the University of Victoria will make up the difference for the north in years ahead.

Without a spike in immigration or births there will be fewer university graduates in northern B.C. a decade from now.

A closer look at specific towns reveals even larger challenges.

Consider Granisle, a community of 303 residents some 50 kilometres north of Highway 16 between Burns Lake and Houston.

It derives 87% of its annual tax revenue from residents, and yet 82% are over the age of 40.

There are only 10 people under the age of 14 in Granisle, according to the most recent census. With virtually no industry, and little recent progress on Pacific Booker’s proposed Morrison mine in the area, how many people will remain in Granisle a generation from now?

How about the village of Hazelton? It derives 72% of its annual tax revenue from residents, yet 57% of its 270 residents are over the age of 40.

There are 14 municipalities in central and northern B.C. that derive 50% or more of their annual tax revenue from residents, and nearly every one of them is trying to find ways to get more young people into their communities.

Industry, of course, will argue that their major projects help address this problem.

They do – an industrial boom will bring more people to the region, for a time.

Thanks to the oil and gas sector, the median age in Fort St. John is 30. But what percentage of workers under 40 in B.C.’s Peace region have permanently moved there?

Certainly, northern B.C.’s airports wouldn’t continually be breaking passenger traffic records if everyone who worked up here bought a house up here.

Although major industrial projects such as gas plants, pipelines and mines catalyze the economy, their workforces are increasingly transient.

There hasn’t been a purpose-built “company town” in B.C. since Tumbler Ridge was carved out of the wilderness to make way for the northeast coal sector in 1981 (previous to that was the ghost town of Kitsault, built in 1979 to support a moly mine).

At a time now when volatility seems to be the new norm for global commodities markets, as seen in Tumbler Ridge, Fraser Lake and elsewhere, home-buyers are less likely to make long-term investments in one-industry or no-industry towns.

Certainly, even if commodities markets were on the upswing, the north doesn’t have the labour force to meet industry’s needs today.

That labour shortage drives up project costs and, in really small towns, means retail shops are constantly in need of people to man the till because their most recent hire jumped ship to make $100,000 per year working for the plant, mine or mill.

What happens a decade from now when the market peaks again, but there are even fewer young workers, and cash-strapped municipalities are still struggling to pay for deteriorating infrastructure?

The north doesn’t need an industrial boom – it needs a baby boom. •

Joel McKay ([email protected]) is director, communications, at Northern Development Initiative Trust, a non-profit organization that stimulates economic growth in northern B.C.