The massive Panama Papers data leak shines a light not only on the dirty money being shuffled through tax havens, but also on the legal and common use of offshore accounts to significantly cut tax payments, say Canadian tax haven experts.

“We see how easy, how common it is to use tax havens for wealthy individuals and corporations,” said Alain Deneault, author of Canada: A New Tax Haven.

“Each time we face that kind of revelation [information leaks], we see the same phenomenon: wealthy people using structures in order to bypass not only the fiscal system but also the legal system.”

The 11.5 million documents from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca revealed the business dealings of some of the world’s most powerful people, including Russian President Vladimir Putin and Iceland’s prime minister – who stepped aside last week in response to the revelations.

The leak prompted governments around the world to promise immediate action. In Canada, the government has instructed the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) to obtain data from the leak for future investigations. Despite political pressure, the CRA has yet to commit to calculate the gap between the total revenue expected compared with the total tax paid, as countries like the United Kingdom do.

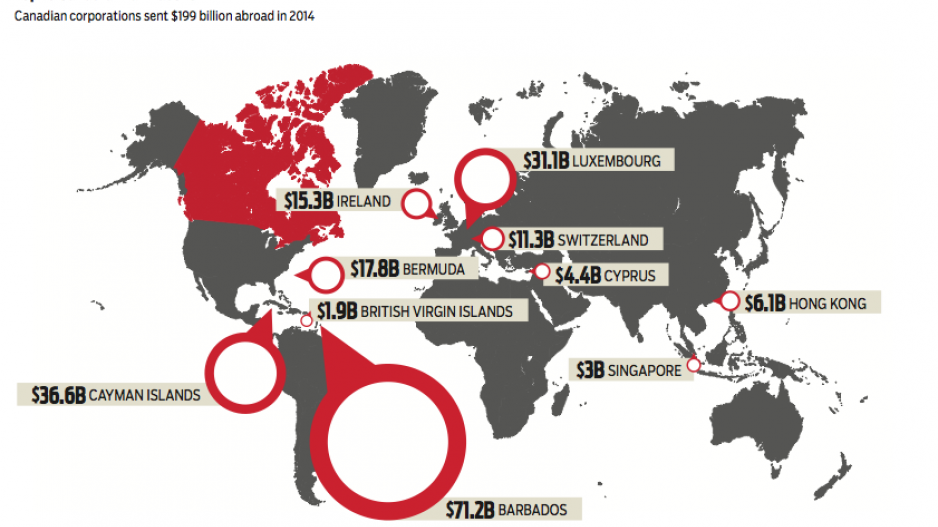

Canadians use offshore bank accounts, and many Canadian corporations use structures like setting up foreign subsidiaries in a tax haven country like Barbados.

“Any Canadian-based multinational is going to look at its international operations and devise arrangements to minimize tax,” said David Duff, a University of British Columbia law professor who specializes in tax law. “Typically they’ll do it legally, and they will generally do that with … a subsidiary that performs a financing function.

The corporate income tax in Barbados is less than 1%, compared with the 20% to 31% a corporation would pay in combined federal and provincial income tax in Canada, Deneault said.

Canada has tax treaties with Barbados and the Cayman Islands designed to prevent companies from being taxed twice.

Silver Wheaton (TSX:SLW), a Vancouver-based mining streaming company, used a foreign subsidiary structure when it set up subsidiaries in Barbados and the Cayman Islands. CRA is now seeking $600 million in taxes owing on income earned through those subsidiaries; the assessment continues to proceed through an appeals process.

Canadian corporations’ tax havens of choice are Barbados and the Cayman Islands, not Panama.

Canadian connections to Caribbean tax havens run deep, Deneault said; in the decades following the Second World War, several well-connected Canadian politicians and lawyers helped to set up the laws and structures that enabled the secretive offshore banking system in the former British colonies.

Today, every major Canadian bank has offices in Barbados and the Cayman Islands, Deneault noted.

The Mossack Fonseca files show the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) (TSX:RY) used the firm hundreds of times to set up shell companies. In response to being named in the files, RBC has said it has procedures in place to ensure all activity is legal and reports suspected tax evasion to CRA. However, even legal uses of offshore banking have negative consequences, Duff said. He’s concerned the use of offshore accounts and subsidiaries has become so common that it is eroding the social contract.

“It’s become easier in a world where people think taxes are bad,” Duff said. “That [idea is] kind of pervasive in the political environment. … And [when] most affluent enterprises have figured out a way not to pay, then other people feel, ‘I want to get my little piece.’”

Effort to end secrecy makes inroads, but Panama is still a holdout

A seven-year effort to crack down on tax evasion using offshore accounts has yielded results, but Panama still remains an outlier when it comes to hiding money from tax and law enforcement, says the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

The OECD stepped up its efforts following the 2008 global financial crisis, and today 132 jurisdictions commit to exchange financial information “on request,” the organization said in a statement released April 7.

That’s still below the goal of automatic information exchange, which 96 countries have agreed to introduce in the next two years.

“The problem with these tax information agreements is that first of all, they generally only involve information exchange the standard is ‘foreseeably relevant’ to the administration with the enforcement of taxes,” said David Duff, a professor at the University of British Columbia who specializes in tax law.

“Canada has to sort of know what it’s looking for in order to go out and look for it, but how do you know what you’re looking for? The increasing standard for information exchange around the world is what’s called spontaneous or automatic information exchange, where the tax agencies just share data.”

For example, that kind of agreement is in place between Canada Revenue Agency and the United States’ Internal Revenue Service (IRS). It has not yet become the standard for tax haven jurisdictions such as Panama, Barbados, the Cayman Islands and many others around the world, Duff said.

The OECD has made inroads in reducing the use of bearer share companies, which figure prominently in many of the Panama Papers stories reported by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and their media partners. Bearer shares are registered without names, and bearer share companies are owned by whoever holds the bearer certificates. Bearer shares can be use to hide the ownership of companies and have been targeted because of their potential to hide money laundering or tax evasion.

But Panama continues to be a problem for the OECD, which describes the country as “the last holdout that continues to allow funds to be hidden offshore from tax and law enforcement authorities.” Panama has recently reversed commitments it had made to adopt automatic exchange of financial account information.

The OECD is calling on Panama to immediately implement the automatic exchange standard.

While Canada’s government recently committed $444 million over five years to the CRA to target tax evasion, it’s a problem Canada can’t solve alone, Duff said. But he also believes the tax advising industry of lawyers and accountants also has a part to play.

“There are lots of data that show multinational enterprises pay a lot less tax than a domestic enterprise,” he said. “Industries have developed around facilitating tax avoidance and tax evasion.”

The difference between tax avoidance and evasion is subtle, Duff said, characterizing avoidance as “the stuff corporations do: that’s often trying to avoid detection too, so you hope not to be audited but if you are audited you have a defensible position.”

The term tax avoidance didn’t exist until the 1920s; getting caught avoiding tax generally means you pay penalties and outstanding tax, not serve jail time.

“Before that people talked about tax evasion,” Duff said. “It was a creation of the tax advisors to invent the concept of tax avoidance.”

@jenstden