Somewhere on Haida Gwaii is a stand of trees soaking up carbon dioxide, although calculating just how much is something of an arcane accounting science.

They’re also soaking up millions of dollars – money taken from school districts, hospitals and universities in the form of carbon offsets.

That is now easier to calculate, thanks to improved transparency in the B.C. government’s Carbon Neutral Government reporting, although it’s hard to say who the money is going to.

According to the recently released 2015 Carbon Neutral Government report, the B.C. government collected $15.6 million in carbon fines in 2015 from school districts, health authorities, Crown corporations, universities and colleges that failed to meet the government’s carbon neutrality mandate.

Of that, $7.2 million was paid to various private corporations and conservation projects in the form of carbon credits to help finance projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs).

The bulk of that $7.2 million – $4.5 million – went into the one sector that many experts say is the least effective when it comes to getting measurable reductions in GHGs: forestry conservation.

As in previous years, the hardest hit among the school districts in 2015 were Surrey, which paid $388,750, and Vancouver, which paid $361,950. The Fraser, Interior and Vancouver Coastal health authorities each paid close to $1 million.

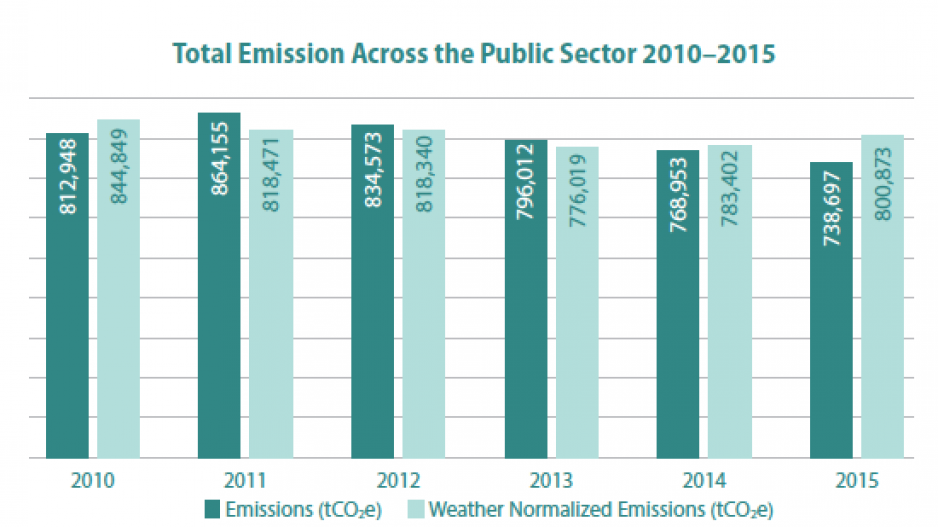

According to the report, B.C.’s public sector has achieved carbon neutrality for the sixth year in a row, producing 44,000 fewer tonnes of GHGs than in 2010.

But when the data is “normalized for weather,” the public sector generated more GHGs in 2015 and 2014 than it did in 2013, according to Hadi Dowlatabadi, a University of BC professor and research chairman for applied mathematics and integrated assessment of climate change.

“They are claiming declines because they’re doing emissions based on actual weather,” he said. “When you do weather normalized, 2014 and 2015 were both higher than 2013. It’s their own data.”

But B.C.’s controversial Carbon Neutral Government plan – formerly administered by the Pacific Carbon Trust – is at least starting to make some progress toward transparency.

For the first time, the report reveals how much each of the 17 projects that qualified for credits received.

In the past, it refused to release that information. In 2013, Business in Vancouver succeeded in an appeal through Information and Privacy Commissioner, who forced the government to release that information.

Last year’s largest corporate recipient of carbon credits was Canfor Corp. (TSX:CFP), which received $1.1 million to help pay for a fuel-switching program in 2015. It has received carbon credits in previous years as well. Canfor has switched five of its B.C. sawmills from natural gas to biomass to provide heat for its drying kilns.

A natural gas plant in Taylor received $335,860 in credits in 2015 to help finance a new transmission line that will allow the plant to replace natural gas power with clean hydropower. A gas plant in Dawson Creek received $185,120 for a similar electrification project.

The actual reduction of GHGs in projects like these is at least relatively easy to quantify. The least effective, and hardest to measure, is investment in forestry conservation, and yet they continue to be the projects in B.C. that receive the most carbon credit investments.

In 2015, forestry conservation projects in the Great Bear Rain Forest received $4.2 million – one on Haida Gwaii and on the north and mid-central coast. A smaller amount – $297,458 – went to a conservation project for a community forest near Whistler.

One of the biggest criticisms of the Carbon Neutral Government policy is that it penalizes school districts like Surrey that can’t meet its carbon neutral targets because its enrolment is growing, forcing students into portables, which are not energy efficient. The districts are therefore being penalized for not receiving enough capital funding from government to meet the government’s own carbon neutrality targets.

The government provided $14.5 million in 2015 to help the public sector invest in energy efficiency projects, but clearly it’s not enough for some institutions to meet their targets.

Another criticism is that the program pumps so much money into the least effective GHG reduction strategy. In 2013 and 2014, the B.C. government invested $23.7 million in 23 offset projects. Roughly $15 million of that went into forestry conservation projects – 61% of the funding.

Dowlatabadi doesn’t think carbon credits should be used to fund forestry conservation projects. As he points out, the reductions in CO2 emissions that result from simply letting trees grow is difficult to calculate and can be wiped out with a single forest fire or pest infestation.

Mark Jaccard, professor of sustainable energy in the School of Resource and Environmental Management at Simon Fraser University, agrees with Dowlatabadi. He adds that even when the GHG reductions are easy to quantify, that doesn’t mean there is a net climate change benefit if it fails the additionality test.

Additionality is the principle that a GHG reduction initiative could not be done without carbon credits. Projects that receive funding but fail the additionality test are known as “free riders,” and in 2013 an auditor general’s report concluded that the majority of the projects funded in 2010 were free riders that failed the additionality test.

“Just because something is ‘measurable’ does not mean it reduces GHGs,” he said. “It has to be something that was otherwise not going to happen – for sure.”

Ben Parfitt, resource policy analyst for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, said there is a lack of transparency when it comes to the reporting on the forestry conservation projects.

The 2015 report provides no details on who is actually receiving the money, or for what specific purpose. If areas that were to be logged are now being protected, there is a distinct lack of details.

Parfitt also shares Jaccard’s concerns about additionality. There are good reasons to protect forests from logging, he said. That should be done anyway. But it shouldn’t be the main focus of climate action policies aimed at reducing GHGs.

“The idea that these forests were going to be protected was certainly there as a strong possibility going back 20 years, well before the idea of carbon credits,” he said.

“I would rather see efforts being made to encourage investment in any infrastructure, public institutions, that is going to result in a demonstrable reduction in their emissions, rather than going out into the market to invest in projects, some of which there are significant questions hanging over them.”

See “Carbon neutral government benefits missing in story,” Letters to the Editor, page 20