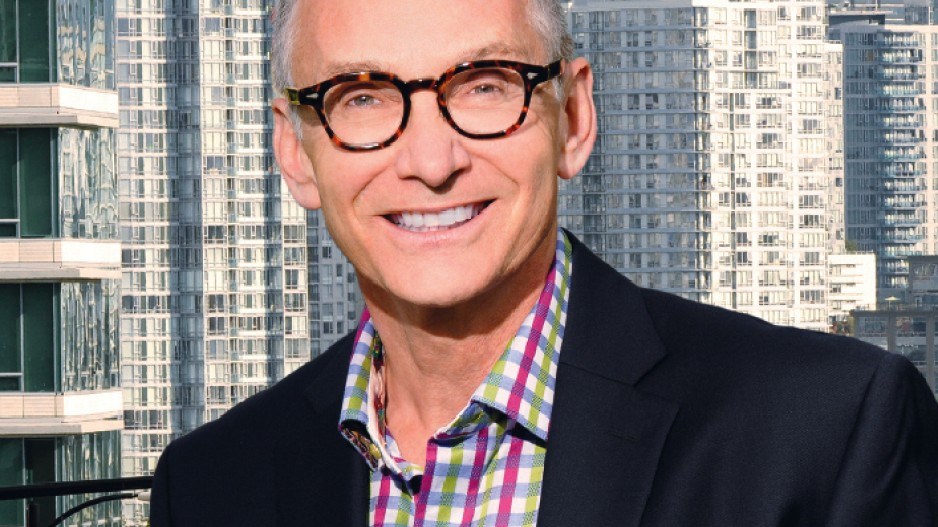

Brian Jackson is dapper, receiving good wishes on this, his last day at Richmond city hall, where he's spent the past four years as director of development and then acting general manager, planning and development.

Round tortoiseshell glasses and smart attire give him the air of a mid-century figure, kindly, precise (he plays bridge) and well-informed (his current reading includes Richard Ford's novel Canada as well as the New Yorker and the Economist).

Preparing to assume his role as general manager, planning and development, for Vancouver on August 20, Jackson's vision is as ambitious as the mandate the city's given him.

"We know that people are going to continue to move to Vancouver, so we need to manage that growth," he said, "and I really believe that you can manage that growth while responding to the issues of sustainability, while protecting single-family neighbourhoods and enhancing neighbourhoods, as well as trying to find ways for people of all income levels to live in Vancouver."

The successor to former planning director Brent Toderian, who was dismissed in January, Jackson was chosen over 107 other candidates following a four-week international search in June for someone willing to work with Vancouver council to address "housing affordability, economic development, citizen engagement and a broad sustainability agenda."

Unlike his predecessors, he'll be part of the city's management team, actively shaping policy while overseeing the rezoning and development applications coming into the city's planning department to ensure that they meet those goals.

Jackson feels the mix of duties will improve the city's ability to address the complex challenges it faces as it matures and is suited to the skills he's gathered over a lifetime of living in and working with cities.

"I looked at my qualifications in terms of the experience that I've had in the public and the private sector, both on the policy side and on the development applications side, and I thought it was a good fit," he said.

Jackson has taken the long way around to reach Vancouver.

Born in Vancouver in 1955, he was raised in Richmond and received first a bachelor's degree in geography and then master's in planning from UBC.

He had always wanted to be a planner; as early as Grade 6, he was building models of Roman villas, and by 16 he was reading books like Jean Gottmann's Megalopolis: The Urbanized Northeastern Seaboard of the United States (1961) and drafting plans for a city in the north for a sciences and humanities symposium.

Graduating from UBC in 1980, he began working for the BC Ministry of Lands, Parks and Housing, then joined consulting firm McElhanney in places as diverse as Nakusp, Port Edward, Stewart and the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District, for which he drafted the first regional plan.

The experience developing plans for local governments and assisting developers to navigate municipal requirements brought him back to Richmond, which was shifting from suburb to city, then Scarborough, where he found himself overseeing major applications for the first time.

His ability overseeing developments in Scarborough's city centre attracted Toronto's notice, which in 1991 assigned him to oversee the city's central waterfront – a sprawling area running from the Canadian National Exhibition grounds in the west to the port lands in the east.

The city was coming to terms with the realities of economic displacement and homelessness in the post-industrial era, and the future of the Gardiner Expressway, the industrial lands along the waterfront and housing the hard-to-house were at the fore.

Jackson helped shape the Harbourfront area. He oversaw infill development and drafted initial plans for the port lands and other areas. And then, from Vancouver, came the Concord Pacific Group, cutting a deal for the lands west of Toronto's SkyDome with a vision of 5,000-plus units of residential. Jackson denies being the architect of what unfolded, but he is proud of laying the groundwork for the area's Vancouver-style redevelopment.

"We brought forward the revisions to a vast area ... that Concord had bought so it allowed for buildings that were up to – in one case – 54 storeys in the railway lands. Council passed that unanimously," Jackson said.

Paul Bedford, then Toronto's chief planner, credits Jackson with introducing him to Concord Pacific's work in Vancouver and opening doors for the company in Toronto.

"The most striking memory I have of him is his clear determination to advance good ideas and make things happen," he said. "He always did his homework and knew the issues before he decided on a course of action. He demonstrated this quality consistently and provided politicians with a well-thought-out position that they could easily understand and digest before making a decision."

Just as significant was the allocation of three blocks of land – enough for 1,500 units – for the development of affordable housing. Government funding dried up and the units have yet to be built, but Jackson said it underscores what's possible – and the challenges of realizing the possibilities.

"You really need partnerships to make it work," he said. "You can create nice bubble diagrams and talk about affordability, but it's much more difficult to walk the talk and make sure that affordable housing is provided."

With Toronto's amalgamation in 1998, Jackson returned to the private sector with IBI Group. Sent to work with San Francisco planner Peter Calthorpe on a project south of Los Angeles, he saw how small zoning changes could accommodate significant growth – an idea he believes could address the challenges Vancouver faces.

"To accommodate a population of six million people, you really only had to look at changing 2% of the land-use base," he said. "I'm not sure in Vancouver's case if it's 2% or 3%, but ... I think we can do it in ways that concentrate it in areas along the major arterials and protect single-family neighbourhoods."

The pledge should do much to reassure those who fear the city's community plan process is laying the groundwork for the redevelopment of established neighbourhoods in the name of density and affordability. All sides want clarity and assurances, and development consultant Gary Pooni of Brook Pooni Associates Inc. believes that's something Jackson offers.

"Brian provides great clarity," Pooni said. "The developer knows what the rules are, the community has great clarity in their community plan, and they know what amenities they're getting."

Jackson isn't fazed at the prospect of balancing conflicting viewpoints.

"My main thesis in life is that planners are the profession in between. We are between the public sector and the private sector, we are between council and the public. My life is all about balance, and trying to find different balances for all those different components." •