If Konrad Walus’ kidneys fail a few years down the road, he figures there’s a strong possibility he’ll walk into his lab at the University of B.C. (UBC) and simply build some new ones.

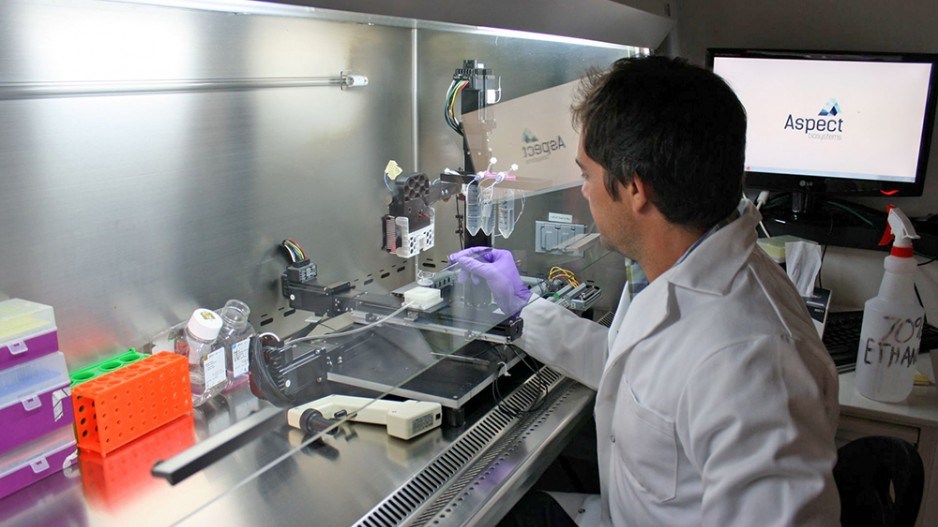

For now, the CEO and co-founder of Aspect Biosystems — one of the 158 companies to spin off from UBC — is content with creating human tissue on demand using his patent-pending 3D printer technology.

Most UBC spinoffs specialize in life sciences, owing to the medical school on campus. Meanwhile, most of Simon Fraser University’s (SFU) 76 spinoffs are focused on information technology.

The goal of Aspect, which earned a $55,000 prize at the BCIC-New Ventures competition in Vancouver September 22, is to provide pharmaceutical companies with complex human tissue better suited for testing drugs than cells in a Petri dish.

“Because we’re actually depositing cells, we can imagine in the future taking a person’s own cells and making those (3D) models,” Walus said.

“Going further, we can make even more complex structures. Organs, that’s the sort of moon shot.”

But convincing companies and clients that all this is possible has been one of the biggest challenges for the company’s four co-founders, whose backgrounds range from medicine to engineering, as opposed to business.

A 2013 study that appeared in Economic Development Quarterly noted life sciences spinoffs are also 40% more likely to fail than others.

However, according to a report from SFU’s Centre for Policy Research on Science and Technology, the survival rate for biotech spinoffs (72%) is only slightly less than for information technology spinoffs (78%).

JP Heale, interim managing director of UBC’s University Innovation Liaison Office (UILO), said there’s often still a steep learning curve for academics entering the business world. He said researchers are often determined to create the perfect bulletproof product, while businesspeople just want the best product possible in the shortest time to bring in sales.

“The UILO certainly takes great steps to educate everybody (about) what the expectations are,” Heale said, adding one of the other challenges is ensuring researchers understand what universities gain from helping them commercialize intellectual property (IP).

“Our licensing practices for local startups, our terms, are much less than they would be for an exclusive licence for someone who’s not a startup and outside of Canada.”

Heale added the university often holds equity in the company and that the UILO is preparing to disclose in the coming months the terms spinoffs make with UBC when it comes to spinning off.

Mike Volker, executive director of SFU’s Innovation Office, said the university does not own any of the IP that comes from research made there.

Instead, its up to the Innovation Office to look at proposals, negotiate a percentage for the university and let researchers decide what’s best for them.

“We’re there as a service and, of course, we try to do a good job because if we don’t do a good job then they can go somewhere else,” Volker said.

One of the key services the Innovation Office provides is helping the spinoffs raise capital.

Both Heale and Volker said getting investors to put money into an early stage company doesn’t always come easy.

“There’s a lot more money out there than there is ideas, but investors are not going to put their money into a company or into a business that isn’t structured properly,” Volker said.