November 11’s gathering of Canadians to remember the country’s soldiers and offer silent thanks for the many sacrifices made, both in the past and still painfully present, is an expression of respect Montreal-born Francis Laparé deeply appreciates.

Laparé, 34, spent 14 years in the military, including two tours in Afghanistan as an infantry officer. He retired from active service in January 2012.

Still, he wishes the show of support for those with military history extended beyond a particular date, and, notably, into the daily workforce.

Like many Canadian Forces veterans who leave the military each year, Laparé found his journey into civilian life surprisingly challenging. His soldier’s skills, highly valued in a war zone, proved of little use to corporate employers who didn’t understand his qualifications as a leader or how they might translate to office culture.

“I would hear, ‘You have an amazing resumé. You have had a crazy life experience and a lot on your shoulders at a young age. Thanks for your service.’ But that is pretty much where it would end,” Laparé said.

It’s an all-too-familiar refrain. A 2011 survey of 140,000 veterans by the Department of National Defence (DND) and Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) found 25% of those released from service experienced difficulties finding their way into a new career.

The roots of the problem go much deeper than perception issues on the part of civilian employers.

For many, including Laparé, serving in the Armed Forces has been the only job they have ever held. As a result, they enter civilian life with little or no experience of the job-application process, how to develop resumés, how to prepare for interviews or how to sell the skills and trades they’ve learned in the military to civilian employers, according to the DND and VAC report.

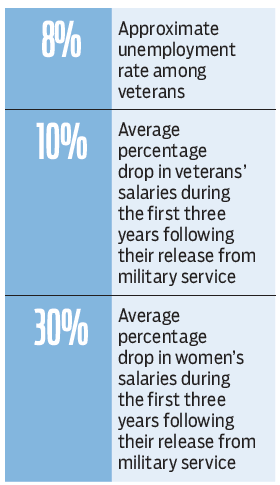

And while the majority of veterans do, eventually, find work (unemployment among veterans is about 8%, the report stated), the new job comes with a significant drop in income.

Another study, this one by DND, VAC and Statistics Canada, found veterans’ salaries dropped an average of 10% during the first three years following their release from military service. For women, the decline was steeper, at 30%.

The study also found that over one-third of veterans received employment insurance at least once post-release.

Adrian Travis, 35, a former Air Force officer who now runs a successful consulting firm in Toronto, said veterans can better their chances of finding career success by connecting with others who have left the service through support groups that exist to bridge the gap between military and civilian life.

Travis volunteers as a mentor with one such organization, Treble Victor Group, a non-profit that helps former servicemen and -women develop business networks, as well as finesse resumé and interview skills. The group is based in Toronto but has active branches in Vancouver, Ottawa and, recently, Calgary.

Other organizations with a similar mandate include Canada Company and True Patriot Love, which acts to connect former military personnel with supportive civilian employers.

Travis said many employers wrongly peg soldiers as hotheads who are too rigidly structured for a civilian workplace.

“A lot of people have images of you stomping on terrorists with your army boots on,” he said.

In reality, many of those with military training offer highly desirable leadership skills, a command presence and the ability to inspire.

“A lot of situations in the military are live-or-die situations,” Travis said. “So, if you need to get something done, these are the people who are going to take it to the hill. They are going to be very, very calm under stress and have a good ability to take a difficult task and break it down. These are the type of people you want on your team.”

Laparé, who, after completing a master’s degree at Ryerson University, now manages construction projects for McDonald’s Canada, agreed with that assessment.

He urged employers to look beyond the specific descriptions of a particular role and to consider the broader, foundational attributes and leadership skills that a veteran can bring.

“At the end of the day, you are going to get an asset that has a very solid foundation for agility, management and innovation in your business,” Laparé said. “It’s just a matter of seeing that and not just focusing on what you are used to seeing in terms of a resumé description.” •