Twenty-five years ago, the forest industry was the mainstay of the B.C. economy, earning over $1 billion in profits and providing satisfied shareholders with a 16% return on their investments.

Of course, the good times couldn’t last forever – forest products is a cyclical business – but the clouds over the horizon were not yet visible in 1989.

Change was coming to the industry. It was to take the form of a prolonged trade war with the U.S., a War in the Woods with environmentalists that would lead to reduced harvests and job losses on the coast, a pine beetle epidemic that would hit 60% of the lodgepole pine in the province and the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression.

Change would also bring:

• A new market in Asia to balance the ups and downs of the U.S.

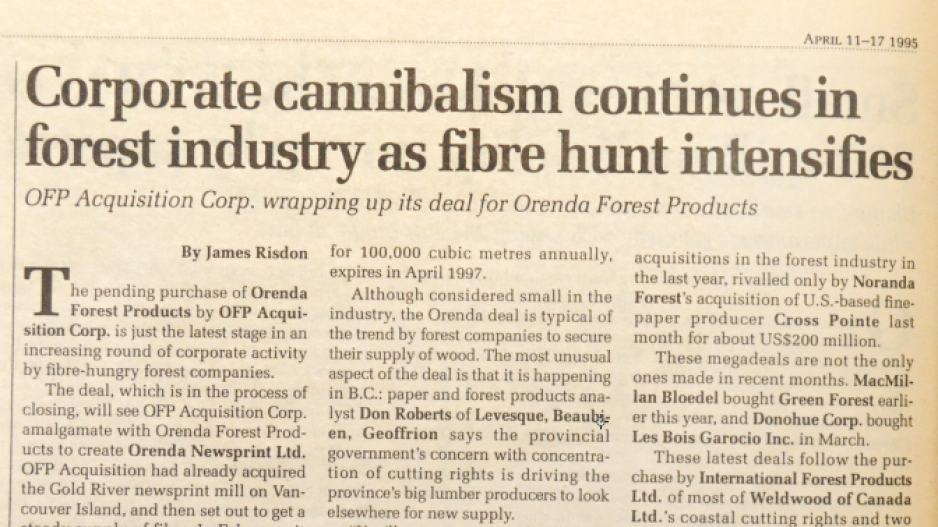

• Corporate consolidation, with new large players shifting from coastal to interior forests.

• A globally competitive industry that has earned its credentials as a green solution to the environmental issues of the 21st century.

• The birth of First Nations-controlled forest companies and forest tenures, stemming from court rulings that both aboriginal rights and title have not been extinguished on the land.

In 1989 the biggest companies were still on the coast. Powered by giants such as MacMillan Bloedel and Fletcher Challenge Canada, the industry was on track for a second year in a row of record sales. More than a quarter of a million people depended on it for their jobs, and forest products accounted for 53% of all manufacturing shipments in the province.

Further, the industry seemed to have weathered the latest assault from the U.S. over lumber exports. A 15% export tax had been replaced by an increase in provincial stumpage fees. The industry was confident the increase in stumpage would satisfy the Americans.

There were environmental issues, but they had more to do with pollution stemming from B.C.’s pulp mills and sawmills. The industry was addressing it; 1989 was a year of record capital expenditures, with $2.3 billion being re-invested. Much of that was spent on reducing emissions, said Bruce McIntyre, leader of the forest, paper and packaging industry practice at consulting firm PwC.

“Remember dioxin? It was a big thing at the time. Billions of dollars went into capital investment in environmental improvements in pulp mills. You will find they are pretty good on their effluents now,” McIntyre said. “And remember beehive burners?”

Cleaning up effluents and eliminating wood waste turned out to be a boon for the industry. Sawdust and wood waste is now termed residual fibre.

“There was value in those residual fibres. Then things like greenhouse gases became important; green energy became important. It wasn’t just cleaning up the air. It was generating value,” McIntyre said.

By 1990, however, the $1 billion-plus profit had been totally wiped out and replaced by a $9 million loss. The U.S. housing market had collapsed, the first of three cycles of steep declines following high prices that would mark the next 25 years.

“Despite the fall in employment, the forest industry still generated 17% of the jobs in B.C.,” reported PwC in its 1990 report on the state of the industry.

It was in this climate of loss that, in October 1991, Ottawa unilaterally terminated its Memorandum of Understanding on softwood lumber with the U.S. The Americans responded by imposing softwood lumber duties, initiating a lengthy trade war that would only be settled in 2006 with the Softwood Lumber Agreement.

International trade was preoccupying industry C-suites, but after smouldering for years, in 1993, the War in the Woods erupted at Clayoquot Sound on Vancouver Island. Telephone companies in Japan were targeted for printing their phone books from pulp made at Port Alberni. In Europe, Greenpeace was urging the European Community to adopt trade measures against Canada. In Washington, D.C., Robert Kennedy Jr. was using his influence to brand British Columbia as a destroyer of the environment. The world watched as police dragged 800 peaceful protesters off a Clayoquot logging road. It was the beginning of a new form of environmentalism, combining both protest and market campaigns to promote change. It soon spread to the next battleground: the Great Bear Rainforest. By 2001, industry and environmentalists had resolved to seek a solution both could live with.

“Our customers told us they were tired of receiving truckloads of lumber with a protester hanging off the back,” Western Forest Products’ chief forester Bill Dumont said at the time.

In January 2014, the two parties signed an agreement that protects about 70% of the region’s forests.

In the 21 years from the Clayoquot protests to the Great Bear agreement, the B.C. forest industry had undergone a huge metamorphosis. The big coastal companies are all gone: MacMillian Bloedel was swallowed by U.S. giant Weyerhaeuser in 1999, which in turn sold operations to Doman Industries’ successor, Western Forest Products. Fletcher Challenge morphed into separate lumber and pulp companies. As the coast slipped in economic importance, globally competitive companies with a strong interior focus emerged.

Canfor sold its coastal assets to focus solely on the interior, swallowing rival Slocan Forest Products in 2004. West Fraser Timber and Tolko were on their own buying sprees. West Fraser bought Weldwood and Tolko acquired rival Riverside Forest Products in a hostile takeover. The province’s three biggest forest companies were now based in the interior. Before they had finished digesting their acquisitions, however, they were hit by the double whammy of the mountain pine beetle and an unprecedented collapse of the U.S. housing market. The beetle infestation began as relatively limited outbreaks but soon swept across the interior, affecting almost 60% of the province’s pine stands. It is considered to be the worst environmental disaster in B.C. history. The province increased timber harvests and required companies to focus on beetle-attacked wood. Sawmill production got an short-term boost.

By 2006, as the beetle attack crescendoed, the U.S. housing market collapsed. By 2009, 20,000 jobs had been lost. The industry had also lost its dominance as B.C.’s economic engine. By 2012, exports of B.C. wood products as a percentage of all exports had slipped to 32% down from 53% in 1989. Direct and indirect employment was 170,000, down 80,000 jobs since 1989.

In the midst of the bloodletting, an initiative begun by then-premier Gordon Campbell in 2002 started to bear fruit: a marketing campaign in China aimed at weaning B.C. from dependence on the U.S. market and its incessant trade irritants. The timing could not have been better.

By 2013, through combined efforts of government and industry, lumber exports to China had grown to $1.4 billion from almost nothing a decade earlier, providing a welcome second market for the forestry sector.

The growth of the Chinese market, coupled with the turnaround of the U.S. housing market over the past two years, has returned a new sense of optimism to the industry, with talk of the coming upturn being a “super-cycle,” where both Chinese and U.S. markets are in need of B.C. wood.

“Markets always pick up,” said PwC’s McIntyre. “That nature of the business is not going to change.”