In a good month, Laura Cairns makes $1,600 doing temp work at warehouses and for fire and flood restoration contractors.

But her pay usually tops out at $1,300 a month.

Cairns, 56, is paid $10.25 an hour, B.C.’s minimum wage. The New Westminster resident has experience as a retail, hotel and office manager, but after a 10-year gap in her work history to care for her aging mother, temporary labour jobs are the only ones she’s been able to find since returning to the workforce.

“There’s no guarantee of hours, and wages are low, so you can barely make it by,” Cairns said.

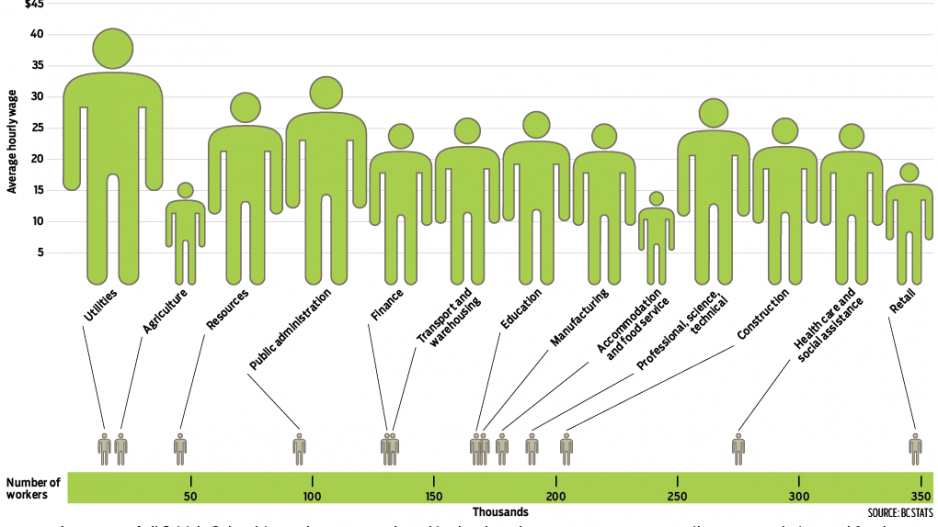

In the eyes of the B.C. government, Cairns is not a typical minimum-wage earner: she’s not a student who still lives at home. Statistics show that 110,000 British Columbians make the minimum wage, representing 5.9% of workers. Over half of those who make minimum wage, 52%, live with their parents; according to the BC Federation of Labour (BC Fed), 47% are over the age of 25.

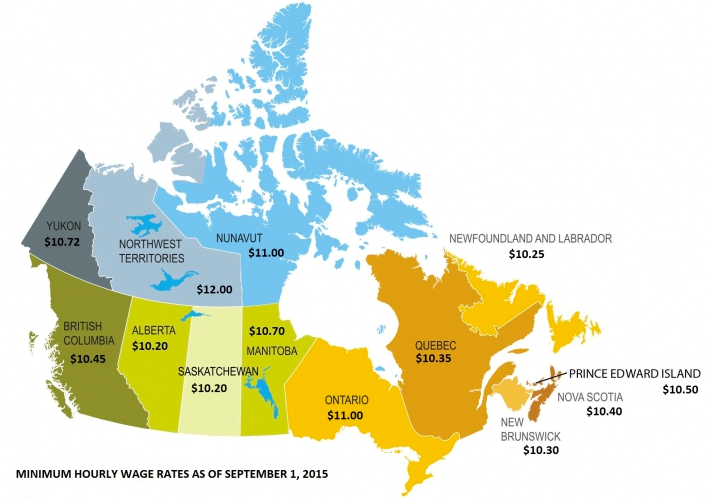

B.C. Jobs Minister Shirley Bond said those relatively small numbers played a part in her government’s decision to raise the province’s minimum wage by just $0.20. The minimum wage will increase to $10.45 from $10.25 in September and will then go up yearly, based on inflation.

Economists, labour leaders and business groups agree it’s time B.C. followed a yearly process for predictable increases to the minimum wage. Other Canadian provinces and several U.S. states already tie their minimum wage to inflation.

B.C.’s previous ad hoc approach led to the province’s hourly minimum wage being frozen at $8 between 2001 and 2011. That stasis was not good for B.C.’s economy, said Jock Finlayson, executive vice-president and chief policy officer at the Business Council of BC.

“We were concerned that freezing it was reducing the purchasing power of the people who are paid at minimum wage,” Finlayson said, “and that it was also going to build up pressure for a big jump in the minimum wage, which is just what happened.”

In 2011 and 2012, the hourly minimum wage was raised in three increments to $10.25.

But there is less consensus on whether $10.45 is still too low. The BC Fed is calling for an immediate jump to $15 an hour, inspired by recent victories in Seattle and San Francisco. Along with other social advocacy organizations, the labour group says raising the minimum wage is important to reduce poverty in B.C.

“If you work full-time, you shouldn’t live in poverty,” said BC Fed president Irene Lanzinger.

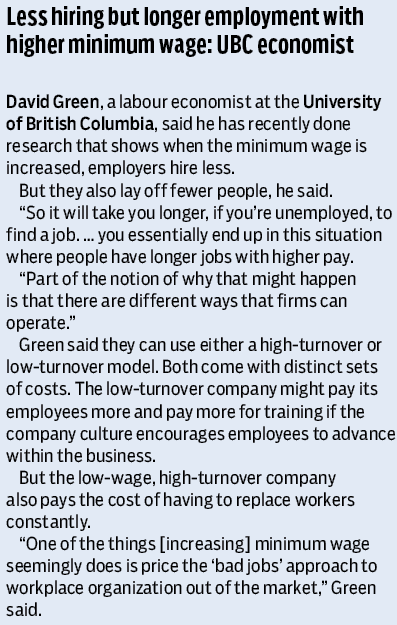

David Green, a labour economist at the University of British Columbia, called the $0.20 increase “practically laughable.”

“Inequality in Canada as a whole and B.C. in particular has gone up dramatically in the past three decades,” Green said. “Little increments in the minimum wage – in this case, an increment that doesn’t even keep up with the consumer price index since the last change – have obviously not done much of anything to prevent that kind of increase.”

B.C. has had either the highest or one of the highest child poverty rates in the country for the past nine years, according to the BC Poverty Reduction Coalition. All other provinces except B.C. have now adopted a poverty reduction plan.

While Bond emphasized the small number of B.C. workers who make $10.25 an hour, the minimum wage affects more than those who earn the lowest pay. According to the BC Federation of Labour, 500,000 B.C. workers – roughly a quarter of all the province’s workers – make between $10.25 and $15 an hour. Increases to the minimum wage put upward pressure on other wages.

That’s a concern for business groups, who say small, incremental changes are manageable – but a big jump would increase labour costs for small-business owners, who will then be reluctant to hire new staff.

Finlayson said studies by economists have shown that small increases in the minimum wage don’t have a negative impact on employment. But far less is known about the impact of a big increase.

“We don’t have a lot of real-world examples in the kind of things Seattle is doing,” Finlayson said.

The Seattle experiment

In Seattle, where 24% of the city’s workers are paid $15 or less, small businesses are bracing for a series of $0.50-a-year increases that will raise the city’s hourly minimum wage to $15 by 2021. (Businesses with more than 500 employees are required to raise the wage quicker.)

Anthony Anton, CEO of the Washington Restaurant Association, said his members will adjust, but “the math has got to change.”

Labour costs currently represent around 36% of business costs for restaurants in Washington.

“If nothing changes and we go to $15, our labour costs will be 47%,” Anton said.

In 1998, when annual minimum-wage increases tied to inflation were introduced in Washington state, restaurants increased food prices every year instead of every three to five years, Anton said. They also tended to hire fewer teenagers, and some eliminated positions like bussers and prep cooks.

Anton expects restaurants in Seattle to make similar decisions as the minimum wage steadily increases over the next six years.

Kelly Gordon, managing partner of a group that owns three Romer’s Burger Bar restaurants in Vancouver, said labour costs make up 32% of the business’ expenses. Around half of the employees make B.C.’s minimum server wage, $9 an hour, which will also rise $0.20 in September. Kitchen staff are paid between $12 and $18 an hour.

To keep up with rising costs, Gordon’s company increases food prices twice a year.

“It’s manageable and it’s predictable as to when it’s going to happen,” Gordon said of the B.C. minimum-wage increase.

“Obviously there’s some pressure to reach $15. That starts to be very scary for us.”

But Mike Wiebe, owner of Eight 1/2 Restaurant Lounge in Vancouver’s Mount Pleasant neighbourhood, said he thinks the $0.20 increase is too low. Because housing costs are so high in Vancouver, many of his employees must live with roommates in order to pay the rent.

“I think $11 is a good amount for people to pay,” Weibe said. “But I think we are trending in the right direction, and having cities like Seattle go to $15 – we can look at the effect of what’s happening in that city and what’s going to work for small business.”

Minimum wage rates in Canada. Source: Business Council of BC

While some Seattle businesses are apprehensive about the change, Anton praised the way the City of Seattle crafted the new law. It worked with labour groups and social service agencies, as well as several business groups, to put the policy in place.

“It gives us time to try things out and test the market,” he said.

The BC Federation of Labour is calling for “$15 in 2015.”

“But we’ve never ruled out discussing some kind of phase-in,” said Lanzinger. “I think [Seattle] did a really good job of getting everybody together and coming up with a plan that took care of everybody’s concerns.”

Cities in Canada don’t have the authority to set a municipal minimum wage. So far, the B.C. government has been adamant that the province’s hourly minimum wage will not go up to $15.

@jenstden