How much would you pay to travel back in time?

It’s possible. I have. Right here in this province – Kitsault, B.C., circa 1983.

I found myself in Kitsault earlier this month not only to learn more about Kitsault Energy Ltd.’s proposed liquefied natural gas (LNG) project, but also to see what in recent years has become an Internet phenomenon and attraction: a wholly intact ghost town in B.C.’s remote northwest that was abandoned the year M*A*S*H went off the air.

Here’s a Kitsault recap for the uninitiated: the town was built in the late 1970s to serve the nearby Amax Inc. molybdenum mine.

Moly prices crashed in 1982-83, and the mine was shuttered.

The town’s 1,000-or-so residents were told to leave by Halloween 1983.

Because the company owned the homes, practically everything was left behind.

When Virginia millionaire Krishnan Suthanthiran bought the town sight unseen for approximately $7 million in 2005, he wanted to turn it into a world-class health and wellness resort. He has renamed the town Chandra Krishnan Kitsault – “Heaven on Earth.”

Why not?

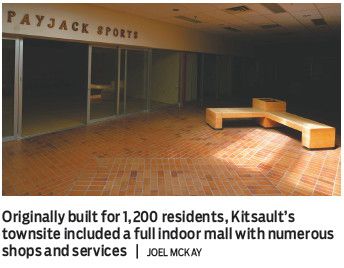

The town is nestled among the Coast Mountains along the glacier-fed waters of Alice Arm and boasts 90 homes, 150 apartments, a mall and recreation centre with pool, hospital, pub and curling rink.

It’s also fully serviced by BC Hydro.

Suthanthiran hired caretakers – a husband-and-wife team – who rolled up their sleeves to wipe away two decades of neglect.

Ten years later, the caretakers and their grounds crew are still at it, mowing lawns and cleaning tree-lined suburban streets in front of empty homes with an eerie Dharma Initiative-like discipline.

The sensation of being transported back in time is only strengthened as you walk inside Kitsault’s homes and buildings.

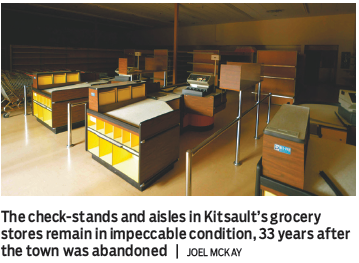

The homes still carry the faintly mournful autumn palette of the early 1980s – dark oranges, oxbloods, harvest golds and olive greens. The library in the community centre is clean and the books neatly ordered. The brown veneer check-stands in the grocery store don’t show a single nick or scratch.

An old copy of the Kitsault Times leads with the above-the-fold headline “Shoppers of all ages celebrate mall opening,” while a nearby issue of Maclean’s asks, “After Joe, what? The anatomy of defeat.”

This incomparable time capsule, severed from the world for 33 years, is set to be transformed into an LNG export terminal.

To a certain degree, it makes perfect sense.

After all, Kitsault was built to serve industry.

It has the infrastructure in place to support a large workforce (during construction and operation) and access to a deep-water port.

It’s also relatively close to northeast B.C.’s gas-rich Horn River and Montney basins and is right in line with Spectra Energy (NYSE:SE) and BG Group’s (LSE:BG) proposed Westcoast Connector pipeline.

Now that BG Group is subject to a takeover by Royal Dutch Shell (LSE:RDSA), which already has its own LNG project in Kitimat, Spectra’s Westcoast Connector could become a pipeline without a project.

Suthanthiran hopes Kitsault Energy can pull the upstream and downstream partners together to bring the project to life and, perhaps, bring people back to Kitsault.

Yet, according to the caretakers, there is no shortage of people who want to visit Kitsault – and not because of LNG.

The privately owned town turns away many would-be visitors each year and yet has still become a phenomenon online.

During the last three years, the number of pictures and media articles published online about Kitsault has increased exponentially.

The University of Northern British Columbia now offers an experiential tourism course that takes visitors – for a $3,600 fee – to experience Kitsault and other ghost towns.

Kitsault is popular again, and not as a health and wellness resort or an LNG terminal but as a time capsule for generation Xers and millennials who crave a simpler time – an age of Atari, televisions with rabbit ears, Knight Rider, Wheaties cereal, Wayne Gretzky, Billie Jean and harvest-gold refrigerators.

In business they say you should always try to capitalize on your strengths, characteristics that make you or your product unique.

What makes Kitsault unique is not its deepwater port or its proximity to gas fields or Asian markets.

What makes Kitsault unique is a perfectly preserved history that could be leveraged to serve a market that craves nostalgia.

That Kitsault qualifies as a national historic site, I have no doubt, but what if it was a place where people could travel back in time?

A place where, for a fair price, you could visit the early 1980s.

I bet my generation would pass over the money without even thinking about it. I’d go. I love watching reruns. •

Joel McKay ([email protected]) is director, communications, at Northern Development Initiative Trust.