When Royal Dutch Shell PLC (Nasdaq:RDS.A) and its partner, PetroChina (Nasdaq:PTR), announced they were pulling the plug on the Arrow LNG project in Australia at the end of January, some analysts read it as a sign that a similar-sized project in B.C. could also be in trouble.

Shell and PetroChina are also the key partners – along with Mitsibishi (Nasdaq:MTU) and KOGAS – in the LNG Canada project in Kitimat, considered one of two front-runners in the race to build B.C.’s first large LNG plant and export terminal.

But at a recent address to the Vancouver Board of Trade, LNG Canada CEO Andy Calitz said the consortium Shell leads is still on track to make a final investment decision in 2016.

Unlike the other front-runner – Petronas – LNG Canada already has all of its provincial and federal environmental approvals, not to mention the support of key First Nations, notably the Haisla. In recent years, Shell has moved from being primarily an oil company to one that now produces more gas than oil. But its business is still largely reliant on oil revenue, which is down. Calitz admitted oil prices need to bounce somewhat for investors to feel confident about taking a multibillion-dollar plunge in B.C.

While Shell might have seemed a laggard in the LNG race compared with Petronas – which has already taken a conditional final investment decision (FID) – its more calculated and deliberate approach appears to have avoided some of the problems now plaguing the Petronas project.

Because of the site Petronas chose, a federal environmental review that was supposed to take 365 days is now past the 700-day mark, and the project now faces an aboriginal title claim from the Lax Kw’alaams Band.

By contrast, Shell bought an industrial site from Rio Tinto Alcan in Kitimat, where the Haisla are willing partners. In addition to environmental certificates for the LNG plant itself, TransCanada Corp. (TSX:TRP) received an environmental certificate for the Coastal GasLink pipeline that will move natural gas from northeastern B.C. to Kitimat.

There are 19 First Nations along the corridor, and Calitz said the project has the support of the majority of them.

In an interview with Business in Vancouver, Calitz, citing commercial competitive reasons, would not confirm the total capital cost of the project, which has been estimated at US$40 billion.

“If you ask me, ‘Andy, how much does an LNG plant cost that produces 12 or 13 million tonnes of LNG from two trains – whether it is built in Canada or Mozambique or in the Gulf of Mexico?’ the answer to that is $50 billion.”

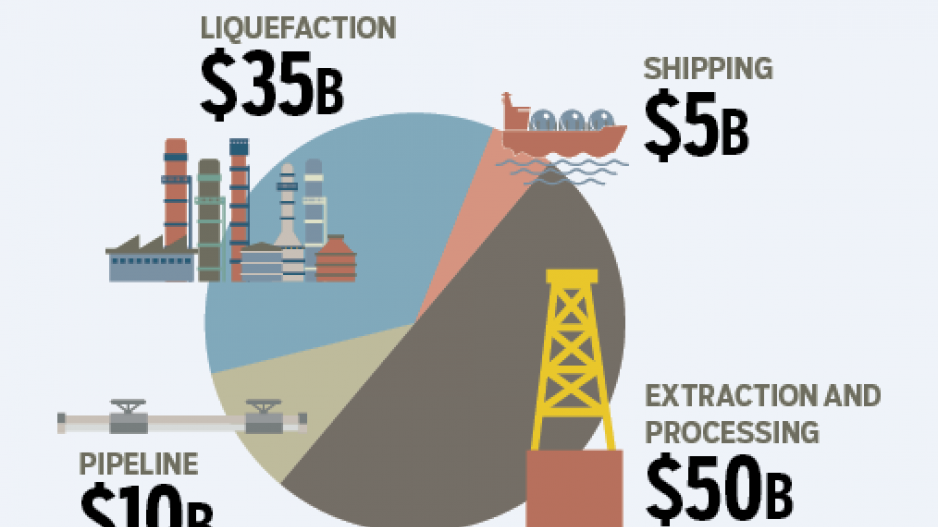

That includes upstream natural gas assets, a pipeline, LNG plant and LNG carriers, which come in at around $300 million per ship.

The investment magnitude of a large LNG project like the ones Shell and Petronas have proposed can be difficult to grasp.

“Any LNG project is the world’s largest industrial project,” Calitz said. “Compare it with any other industrial project that manufactures something; there is nothing larger.”

To put it in perspective, a single LNG project on the scale Shell is proposing has a capital cost equal to that of the Three Gorges Dam in China (US$26 billion), the Milan-Bologna high-speed railway (US$9 billion) and the widening of the Panama Canal (US$5.25 billion) combined.

The project would require thousands of workers. High labour costs were one of the main factors that caused budgets to balloon in Australia, including on the massive Gorgon gas project. Shell is one of the partners in that project, which went US$15 billion over budget.

Calitz said he learned a hard lesson from the Gorgon project: “think labour, think labour, think labour.”

Canada has a number of advantages over Australia when it comes to labour, Calitz said.

One is B.C.’s “connectedness” with other provinces. The other is that the B.C. government showed foresight in identifying early on that it would need to train or recruit thousands of workers and has worked with industry on developing trades training.

“That vision, two or three years before an LNG FID took place … is the single biggest difference,” Calitz said. “The premiers of Western Australia … did not sit down with industry to the same degree and say, ‘How do we cope with this?’”