Unlike, say, Canadian lumber or cattle, software and data created in B.C. already transfers nearly instantaneously between countries – no container ships required.

But the Trans-Pacific Partnership’s (TPP) efforts to reduce any remaining hurdles blocking the flow of digital goods between participating countries could backfire for tech companies facing new obstacles ranging from intellectual property (IP) rights to server security, B.C. experts say.

Highline CEO Marcus Daniels, whose accelerator invests capital in startups, said the agreement might be positive for many traditional Canadian industries but is “potentially dangerous for several innovation-driven sectors such as tech.”

“Superficially, having premium access to the world’s largest trade zone should help growth, but the devil is always in the details,” Daniels said. “There [are] several deal items that need deeper analysis to ensure we’re not at a disadvantage. In particular, how IP standards are set, [which] deeply impacts scalable tech companies.”

For instance, the full text of the TPP reveals members “shall provide for criminal procedures and penalties” for anyone who attempts to circumvent a digital lock on a program or device.

That provision would protect tech companies’ IP, but engineers or developers trying to examine a competitor’s product and build innovations on top of it could face jail time, curtailing further advancements in technology.

Daniels said part of the problem is that the government was out of touch with the tech sector during negotiations.

“Also, there has been very little understanding of which people and organizations are driving real impact over activity in the ecosystem,” he said.

“The onus is now up to a few leaders in the tech sector to band together to drive a more reflective voice that can impact positively...tech companies that headquarter in Canada.”

Bill Tam, president and CEO of the BC Technology Industry Association, said the most important aspect of the agreement is that it reinforces standards for the tech industry in emerging markets – Malaysia and Peru, for example – that are similar to those in Canada.

This would be especially helpful for companies that make cryptography- and security-related products, Tam said, adding that the full text of the TPP shows those firms would not have to reveal source code when delivering products.

“That, in effect, provides the necessary protection for a lot of companies seeking to do business overseas,” he said.

Vancouver-based Absolute Software (TSX:ABT), which develops security products for computers and mobile devices, would not comment specifically on the TPP, but spokesman Toru Levinson but told Business in Vancouver the company’s policy of keeping its customer data on Canadian servers is one of its selling points for foreign clients.

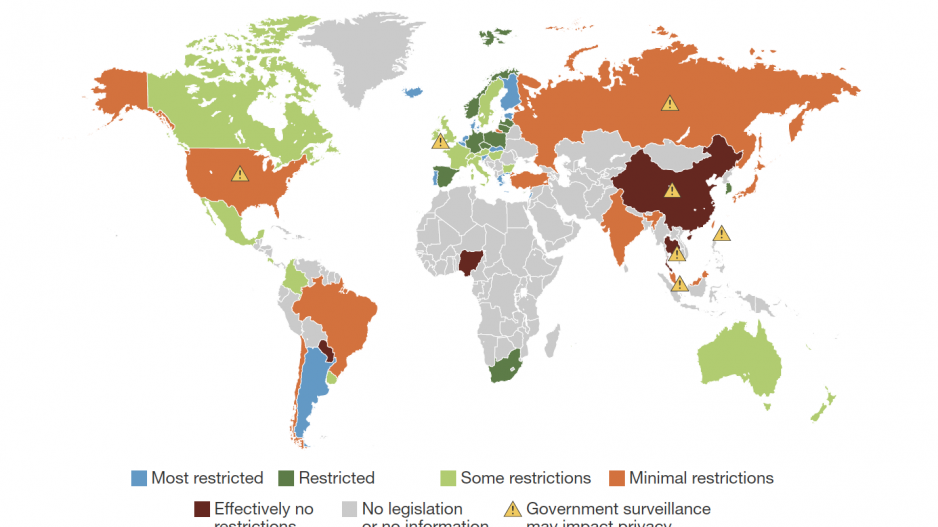

This is because Canada, unlike the U.S., the U.K., Russia and China, is not among the countries listed in Forrester Research’s 2015 data privacy report as at risk for privacy violations due to government surveillance.

“Our customers often find comfort in knowing that we adhere to fairly tight restrictions and regulations,” Levinson said.

But the BC Freedom of Information and Privacy Association (FIPA) has raised concerns TPP provisions could override B.C. law governing data storage.

Victoria enacted laws requiring sensitive data be kept within Canada after concerns arose in 2004 that B.C. health data could be subject to the U.S. Patriot Act if stored outside the country.

The TPP, however, states governments cannot require companies to use servers within their own borders as a condition for conducting business.

“There are lots of dangers there,” FIPA executive director Vincent Gogolek said, adding his organization is still examining the 6,000-word trade agreement to see if and how it undercuts Canadian law.

He pointed to the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative’s 2014 report that determined B.C.’s data storage law “hinders U.S. exports of a wide array of products and services.”

“This policy precludes some new technologies such as ‘cloud’ computing providers from participating in the procurement process,” according to the report.

If the U.S. government views the law as a barrier to trade, Gogolek said it’s likely to be brought before a TPP arbitration panel even if the B.C. government does not consider the practice to be discriminatory against TPP partners.

“Hopefully we won’t have to have a rerun of the big battle that we had that got these provisions put in in the first place,” he said.

But governments are permitted to require servers to be located within their borders if the goal is “to achieve a legitimate public policy objective,” according to the full text of the agreement.

“I don’t see the major alarm bells going on about the privacy issues that have been raised by others,” Tam said.

“It doesn’t, from my read of it, undermine the existing requirements that we have here in B.C. or other jurisdictions that might have similar rules. What it does say is that you can’t use those sorts of attributes in such a way that it would prove to be discriminatory in any way or excessive in any way.”