When he was 17 and fresh out of high school, Squamish Nation Chief Ian Campbell jumped at the chance to spend two months living with the Mapuche people in Chile as part of an indigenous peoples’ exchange funded by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA).

The welcome he got his first night in post-Pinochet Chile, which was still something of a police state, wasn’t quite what he expected.

“We were thrown against the wall, with guns to our heads,” Campbell said. “We were like, ‘OK, welcome to Chile.’”

But that wasn’t Campbell’s first experience with police pointing guns at him. He experienced that growing up on reserve in North Vancouver.

“There were very negative interactions with police, where they were pulling their guns on us as youth, and beating us up and calling us racial names,” he said. “There was quite a bit of racism back then, growing up, that really frustrated me to want to get more involved in leadership and politics and changing this narrative of Canada.”

The 42-year-old hereditary chief went on to develop a skill set that combines traditional knowledge with business and political acumen and an ambition to bridge cultural and economic gaps.

He is one of only a dozen Squamish First Nation members who are fluent in the Squamish language, and his business education includes an executive MBA.

He pursued counselling and youth studies at Langara College, later attended the Ch’nook Indigenous Business Education program at the University of British Columbia’s Sauder School of Business and last year capped off his education with an executive MBA from Simon Fraser University’s Beedie School of Business.

It’s that mix of traditional knowledge, ambition and education that led Chief Gibby Jacob to tap Campbell in 1999 to serve as a lead negotiator in the Squamish Nation’s office of intergovernmental relations, natural resources and revenue.

“He was my first hire,” Jacob said. “That was a direct hire – I didn’t go searching for anybody. I just knew what I needed and he was the guy. I was very impressed with how he carried himself, handled speaking to the public, his knowledge of our territory and language and traditions.”

The general public can be forgiven for thinking Campbell is the chief of the Squamish Nation; he is, after all, one of 16 hereditary chiefs. But he’s not the chief.

The Squamish Nation has no chief. According to the custom election system it adopted in 1981, the Squamish – a confederation of 16 groups – has an elected council and two co-chairs, but no elected chief.

Campbell is the Squamish nation’s official spokesman and ambassador, however.

“I’m a hereditary chief and I’m a political spokesperson and elected rep,” he said. And since so much of what he does involves economic development, you could also say he’s a businessman.

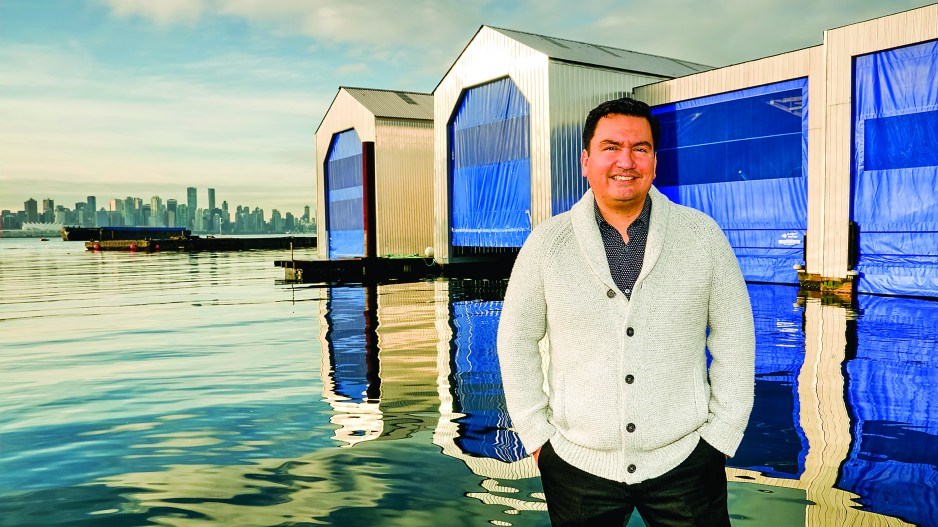

Born and raised on the Eslha7an reserve around the Mosquito Creek Marina in North Vancouver, Campbell (whose Squamish name is Xalek), was groomed by his grandfather, Chief Lawrence Baker, from a young age to inherit his title.

“My parents separated at a young age, when I was three and a half, so I kind of circulated around with my mom, then my dad, then my grandparents. But I always went back to my grandparents.”

As the future heir to the hereditary chief’s title, Campbell was brought up learning to speak the Squamish language. He and his sister are among only about a dozen Squamish members who are fluent in the language, he said.

“My grandfather also brought me out onto the land quite a bit from a young age – mountaineering, hunting, fishing, getting up there into the territory where he shared a lot of the mythology, the history, the old villages, the lineages that connect our people and our ancestral names to the territories.”

Campbell’s work with the Squamish Nation’s intergovernmental relations, natural resources and revenue office includes governmental affairs and economic development.

“We’ve been sort of the one-stop shop where we wear a number of hats: political, negotiator and then business implementation,” he said, adding that one of the Squamish government’s priorities will be to separate the office’s two functions and establish an arm’s-length economic development office.

And there is a lot of economic development happening in Squamish territory. A number of major initiatives are in the works, including the $1.7 billion Woodfibre LNG plant proposed for the town of Squamish.

A Day In the Life

When it was proposed, the Squamish Nation decided to undertake its own environmental assessment process. That’s not unique – the Tsleil-Waututh also commissioned its own EA on the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion proposal. But unlike that process, the Squamish EA was done in partnership with the company that plans to build the LNG plant. It’s a legally binding agreement, with 25 conditions that must be met in order for the Squamish to support it.

Campbell admits there has been opposition within his community to the liquefied natural gas plant, mostly due to concerns about the potential impact on Howe Sound.

“Woodfibre has been very divisive,” Campbell said. “A lot of members say to us: ‘Why don’t you just say no?’ And we’re saying, in an ideal world that would be great if we had a veto card to just say no. But, unfortunately, if we say no, then we’re going cap-in-hand, asking someone to consider our interests. Then we’re on the outside looking in.

“We said the greater certainty for us to exercise our governance and jurisdiction is to create our own process, which is legally binding. We don‘t have legislation like the province, therefore we rely on legally binding agreements.”

Although the LNG project could provide substantial economic benefits for the Squamish, real estate development is the biggest economic generator.

The Squamish Nation is among the wealthiest First Nations in Canada. That’s partly because of location. Squamish territory includes some of the most valuable real estate in Canada, stretching from Point Grey in Vancouver to West and North Vancouver, and north to Whistler.

With 24 reserves, the Squamish Nation generates revenue through leasing some of its reserve lands. But it also owns and operates a number of businesses – from gas stations and marinas to a forestry operation – and has been very successful in negotiating new land parcels from senior governments.

The Squamish initially entered B.C. treaty talks but abandoned that process in the mid-1990s for direct government-to-government negotiation.

It obtained 1,200 acres from the B.C. government when BC Rail was sold off, and partnered with the Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations to obtain former federal land known as the Jericho lands in Point Grey, which they plan to develop jointly in partnership with the Canada Lands Company.

The 2010 Winter Olympics presented the Squamish with a host of economic opportunities as well. As part of the Sea-to-Sky Highway improvements and other infrastructure projects leading up the Olympics, the Squamish obtained another 1,200 acres of land for development.

While some First Nations in B.C. opposed hosting the Winter Olympics, the Squamish Nation was fully on board and directly involved in the Olympic celebrations.

The Squamish’s leasing and business revenues help augment the funding it receives from the federal government. Its annual budget is $67 million, about 75% to 80% of which is “own source revenue.” From that revenue, each of the nation’s 4,000 members receives $1,000 annually in dividends.

Campbell is driven to ensure that the next generation – including his 13-year-old daughter – will benefit from jobs and economic activity in the Squamish Nation. And he’s optimistic about what he calls the era of reconciliation and the opportunities it presents for indigenous people.

“What are we doing to allow access to resources and wealth creation?” he asks. “It can’t continue to be at the expense of First Nations people, where we’re managing welfare. We want to manage wealth.”

When he’s not working, Campbell spends time in the mountains, where he likes to go backpacking and hunting for deer and mountain goat. He is also an avid paddler – which is not only good exercise, but also a way of connecting with other coastal First Nations.

In 1993, Campbell and other members of the Squamish paddled to Bella Bella for a coastal First Nations festival.

“Every year, since ’93, we’ve been on the water where a community will host each year,” he said.