Back in 1929, several months before the stock market crash that ushered in the Great Depression, the opening of the Vancouver Stock Exchange building generated a lot of local excitement. Stock markets were frothy, and people were excited about having a flagship space to give prestige to the city’s stock exchange.

But it was likely not the most talked about building in town.

While the 10-storey neo-Gothic structure at the corner of Howe and West Pender streets was taller than the eight-storey Sylvia Hotel, which soared above English Bay, it was smaller than closer buildings, such as the 15-storey Vancouver Block on Granville Street and the 17-storey Sun Tower on East Pender Street.

(Image: The Exchange Tower is under construction at the corner of Howe and West Pender streets | submitted)

The real buzz about town centred around the then-under-construction, 22-storey, art deco Marine Building – a structure that was slated to be the tallest building in the British Empire when it opened in 1930.

A similar dynamic is at play today, as tenants such as the National Bank prepare to fill Credit Suisse and SwissReal Group’s $240 million, 31-storey The Exchange tower on the former Vancouver Stock Exchange site in spring 2017.

More buzz surrounds the construction of taller structures, such as the 59-storey Vancouver House or the 63-storey Trump International Hotel and Tower Vancouver, both of which are under construction.

What The Exchange tower has over those taller skyscrapers, however, is a link with its historical past. Architects and engineers involved in the Exchange tower project are doing far more than simply keeping the building’s facade. Instead, they are completely restoring the original building.

They are also linking floors so that people who are on one of the restored building’s L-shaped, 10,000-square-foot floors will be able to walk seamlessly into the new tower. Floors in the combined new tower will have twice that square footage.

The part of the floor that is in the old building will gain stability from being attached to the new building, explained Leslie Peer, a partner at Read Jones Christoffersen Consulting Engineers, which is engineering the tower.

“There’s a sideways load, which is the wind load or the seismic load,” Peer said. “That creates a sideways or lateral force against the building.

“Most older buildings are deficient for seismic loads. What we’re doing is instead of putting a new lateral system into the existing building, we’re tying the existing building to the new building so the lateral loads are taken down.”

The existing building will keep its original elevator shafts in what was its centre.

The new combined building’s elevator shaft and stairwell core is being built to a much higher standard than the one in the restored original building. Not only is the new building’s core sufficient to hold up the new tower, it is also sufficient to provide lateral support for the existing building.

Extra support in the combined building comes from thicker walls in its elevator and stairwell core. Those walls are made out of high-strength concrete and extra rebar.

Because the new building towers directly above the old building starting at the 11th floor, other adjustments were also necessary.

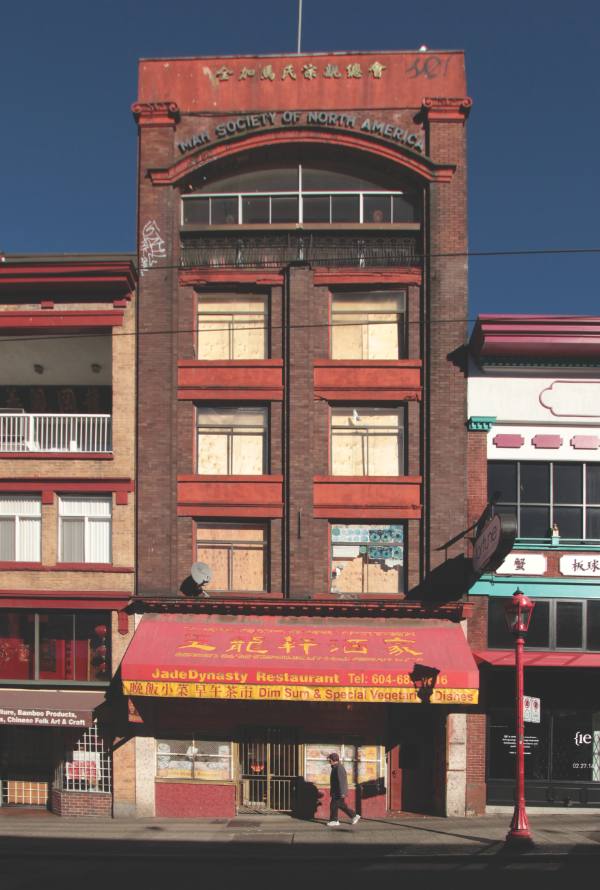

(Image: Chinatown's Mah Society Building at 137 East Pender Street (left) and the Lim Sai Hor Association building at 531 Carrall Street are slated for upgrades this year | Rob Kruyt)

“There’s a new set of columns coming down through the existing building to take the dead loads [of weight] from the new tower,” Peer said.

While The Exchange tower is undoubtedly the most significant blend of old and new construction underway in the city, other heritage restoration projects are about to launch to upgrade even older buildings.

The 97-year-old Mah Society building at 137 East Pender Street and the 107-year-old Lim Sai Hor Association building at 531 Carrall Street are both slated for upgrades later this year, said McGinn Engineering and Preservation Ltd. principal Barry McGinn, who is a consultant on the projects.

He stresses that the projects are not full seismic upgrades but rather extensive facade restorations.

Part of the work, however, will improve the buildings’ stability in a moderate earthquake.

“We’re seismically bracing the parapet of the Mah Society building,” McGinn said, adding that in earthquakes, damage often includes parts of building facades falling to the street.

“There will also be upgrades throughout the building,” he said.

“We’re talking new electrical systems, new plumbing, new finishes, washrooms. We’re upgrading the livability standard, and that’s both from a life-safety standard and from a heritage standard.”•