Legislative changes and investments for Expo 86 helped Canada set a tourism record with 16.2 million visits in 1986, but, more importantly, it laid the groundwork for Vancouver’s evolution into a global tourist destination.

The physical legacies of the world’s fair, such as BC Place stadium, Science World at Telus World of Science and the original Vancouver Convention and Exhibition Centre, have helped promote tourism in Vancouver during the past few decades.

Hosting the fair also spurred new laws to make the province more welcoming for tourists.

Liquor laws reformed

A month before Expo 86 opened, the B.C. government recognized that liquor regulations were out of step with much of the world. Minister of consumer and corporate affairs Elwood Veitch announced what were supposed to be temporary liquor law changes for the five-month-long fair.

Pubs and bars were allowed to open on Sunday, enabling patrons to have a drink without ordering a meal on that day of the week for the first time.

The change proved so popular that the government did not dare revert back to mandatory Sunday closures.

The B.C. government had earlier in the year granted approval for Mission Hill Family Estate Winery owner Anthony von Mandl to sell franchises so franchisees could operate off-winery stores that sold von Mandl’s wine, coolers and cider.

This was the first time that Victoria allowed alcohol sales in retail stores outside of government-run outlets or winery grounds.

Marquis Wine Cellars owner John Clerides, who bought one of those franchises for $10,000, remembers that red tape kept him from opening until Expo 86 had finished.

Good news, however, would come for Clerides the following year, when the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement was signed. International trade laws would eventually force the B.C. government to allow Clerides and others who bought von Mandl’s franchises to also sell international wines, Clerides said.

| See also: The Expo effect: How Expo 86 changed Vancouver Expo 86 Effect: Fair gates to fare gates — how SkyTrain transported city into next millennium |

Physical legacies

The biggest investments in B.C. tourism in the lead-up to Expo 86 were undoubtedly the $126 million spent to build BC Place in 1983 and the $284.8 million spent to build Canada Place in 1985.

With more than 60,000 seats, BC Place was nearly twice the size of Vancouver’s then-largest stadium, Empire Stadium. It enabled the city to host concerts, sports championships and eventually the 2010 Winter Olympics opening and closing ceremonies – events that would have been ill-suited to the 1954-built Empire Stadium.

The federal government paid $144.8 million to build the public portion of Canada Place, including what was the Canada Pavilion for Expo 86. Prime minister Pierre Trudeau announced the funding in late 1982, and Expo’s former chairman, Jim Pattison, credits former B.C. senator Jack Austin, who was in the federal cabinet at the time, as being integral in obtaining that funding.

(Jim Pattison Group owner Jim Pattison worked as Expo 86's chairman and CEO for $1 per year and held his own corporate board meetings at his office on the Expo site | Romila Barryman)

Tokyu Canada Corp., which was controlled by Japanese interests, contributed an additional $140 million to build the adjoining Pan Pacific Hotel and the World Trade Centre complex.

The Canada Pavilion became the Vancouver Convention and Exhibition Centre on July 1, 1987, enabling the city to host larger events.

“We were missing conventions,” said former economic development minister Grace McCarthy, who explained that the province’s role in creating the convention centre included accumulating the land, clearing the site and lobbying for federal funding.

“We would have small conventions come to B.C. but we could not accommodate large conventions. A small service-club convention is very good to have, but it doesn’t bring the millions and millions of dollars that the larger conventions spend.”

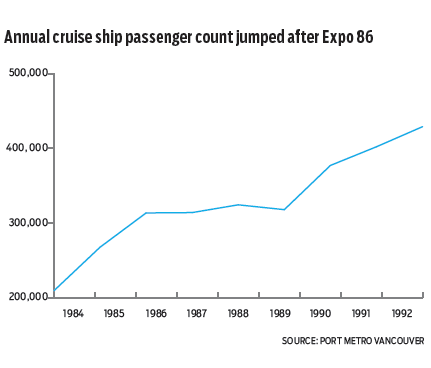

Canada Place also helped tourism by becoming a port for cruise ships. Annual cruise traffic surged more than 17% in 1986 to 313,385 passengers. By 1990, traffic was up another 20% to nearly 377,000 passengers.

Then there is the legacy of what is now Science World at Telus World of Science, which was almost torn down.

The structure was known as Expo Centre during the fair, when it housed an Omnimax theatre with a giant screen that showed films that filled viewers’ peripheral vision.

The Arts, Science and Technology Centre moved from downtown Vancouver to the iconic golf-ball-shaped holdover from Expo 86 after a $17 million renovation, paid for by the federal, provincial and city governments.

The move was controversial.

Peter Brown, who was chairman of the British Columbia Enterprise Corp., which owned and sold the Expo site, did not want to see the structure stay.

(While BC Place Stadium (left) and Science World (right) were kept as legacies of Expo 86, the same was not true of Expo Theatre (center) | City of Vancouver Archives 2010-006.406)

“[Science World] was built as a temporary building and it is a massively inefficient legacy,” he told Business in Vancouver.

“They had to redo all the pilings. It’s an expensive building to run. The more efficient answer was to take it down, but Grace McCarthy insisted that of all of the buildings, that it stay.”

McCarthy told BIV that she believes the centre has done a good job of educating and inspiring young people and that the building itself is attractive so it was a smart move to keep it.

The Plaza of Nations was also initially intended as a temporary structure, and it was also saved, but other structures such as the 4,000-seat open-air music venue Expo Theatre were not.

“You’d put that theatre on the most valuable acreage in downtown Vancouver?” Brown said when asked about why that theatre was torn down. “If you hang onto this stuff, the public takes ownership and it’s a disaster.”

The former B.C. Pavilion, which now houses Edgewater Casino, was always intended to be permanent.

As for McCarthy, her fingerprints are on another symbol of Expo 86 that has been embraced by tourists – the night lighting on the Lions Gate Bridge.

While networking in London, England, McCarthy got connected with the Guinness family, which had originally built and owned the bridge.

The family agreed to pay the cost to install the lights in 1986, while the B.C. government would pay ongoing electricity costs, McCarthy said. •