It wasn’t just that Expo 86 introduced Vancouver to the world and came with SkyTrain, BC Place Stadium, the Vancouver Convention and Exhibition Centre, a new Cambie Street Bridge and other infrastructure legacies.

In the wake of the fair, the site’s sale helped spark the urban revitalization that has established Vancouver atop the world’s most livable cities rankings.

Before the fair, the Expo site was widely viewed as a “blight on the Vancouver waterfront,” according to former B.C. economic development minister Grace McCarthy, who was the minister in charge of British Columbia Enterprise Corp. (BCEC), which owned and sold the Expo site in 1988.

McCarthy was also the person who first suggested that Vancouver host a world’s fair.

She was in London meeting with Patrick Reid, who was in charge of Canada House in London. The Social Credit Party had just won the 1979 provincial election, and premier Bill Bennett had given McCarthy a portfolio that oversaw British Columbia House, a London facility that promoted trade between the U.K. and the province.

Reid was also president of the Paris-based International Bureau of Expositions (IBE), which granted cities the right to host world fairs.

Reid and McCarthy discussed the IBE over lunch, and she asked him why B.C. had never been granted a world’s fair.

“You’ve never asked for one,” McCarthy recalled Reid saying.

“Well, I’m asking for one now,” she responded.

McCarthy told Business in Vancouver that although she didn’t have authority from the premier to commit to a world’s fair, she was sure it would be a huge economic boost for the B.C.

Bennett approved the idea to bid, and Reid convinced IBE directors to grant Vancouver the 1986 world’s fair, originally dubbed Transpo 86.

| See also: Expo 86 Effect: Fair gates to fare gates — how SkyTrain transported city into next millennium Expo 86 gave city stadium, convention centre and new liquor laws |

Transpo 86’s transportation theme fit well with the 100th anniversary of the trans-Canada railroad touching the West Coast. 1986 was also Vancouver’s 100th anniversary.

Victoria changed the name of the fair and created Expo 86 Crown Corp. while Bennett persuaded successful business people to be directors.

Jim Pattison Group owner Jim Pattison was chairman; Canaccord founder Peter Brown was a director and chairman of the Crown corporation’s finance committee.

Both told BIV that the fair helped the province get out of what was a severe recession.

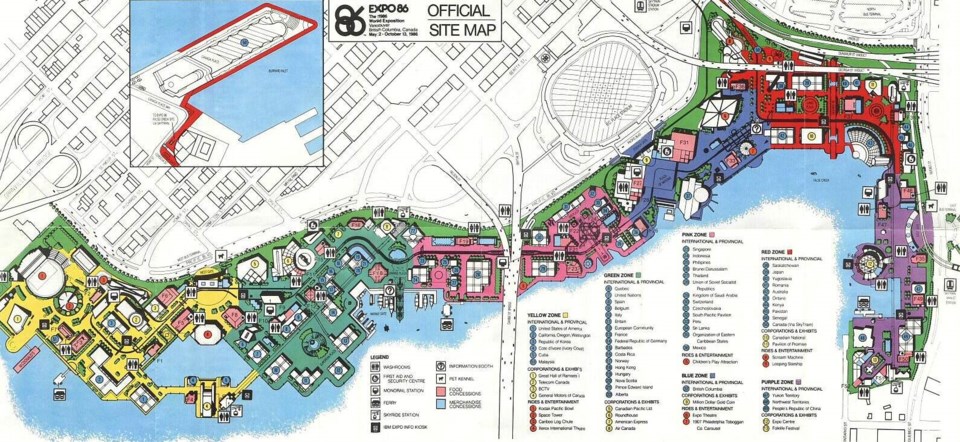

(The purple zone of the Expo 86 site was not part of the sale to Li Ka-shing nor was the part of the site which included the Vancouver Convention and Exhibition Centre)

“1982 was probably the worst recession in our generation’s lifetime,” Brown remembered. “B.C. was particularly hard hit as interest rates went to 20% and half the sawmills in the province were shut down. It was really frightful.”

What Brown called a “hole” in the middle of the city was soon seen as the ideal spot to be the Expo’s location.

“We assembled the land, and we expropriated quite a number of pieces to get it done – sawmills and things of that nature,” Pattison said. “We traded some land with Canadian Pacific (TSX:CP) because they were down there.”

Pattison ran his business from a new office on the Expo site and said he didn’t go into his corporate office for years. The Jim Pattison Group at the time had about $1 billion in annual revenue and 6,000 staff. So it was no small entity.

Pattison told BIV in April that his company had grown to $9.1 billion in revenue and 41,000 employees in 2015. He rarely, in the past, has revealed overall revenue.

Expo 86’s biggest break, according to Brown, came when the Soviet Union agreed to spend lavishly and create a large Expo pavilion that celebrated 25 years since cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space.

“The Iron Curtain was up,” Pattison said. “So anything to do with communism was of huge public interest. We had to have China. We had to have Russia. We had to have Cuba.”

To ensure that those countries were represented, he said, “special arrangements,” and, sometimes, financial help, were provided.

Pattison remembers buying the first rug sold at the Chinese pavilion, which was granted approval to run a store to generate revenue.

He added that the U.S. “was the toughest of all to get to the fair. For the U.S. to participate in a world’s fair, it takes an act of Congress to pass. So there are a lot of hoops you’ve got to jump through.”

In all, the fair had 52 pavilions and representation from 38 countries. Organizers expected 14 million visitors but wound up with 22 million, meaning that many souvenirs were sold out early.

Selling the site

The successful fair left British Columbians in such a good mood in the wake of its October 13, 1986, closing day that voters re-elected the Social Credit government in the October 22, 1986, general election.

Premier Bennett had resigned in August, making Bill Vander Zalm the new premier, and Vander Zalm won a convincing 47-22 seat victory over the New Democrats.

Believing the private sector should develop the 90-hectare Expo site, his free-enterprise government created BCEC in March 1987 and transferred the site’s ownership and other assets to the new Crown corporation. Its goal was to sell the site quickly.

Real estate developer Peter Toigo, a close friend of Vander Zalm and the owner of the White Spot restaurant chain, pitched an idea in 1987 to buy part of the site so he could build a hotel, restaurant and theme park, using existing Expo 86 rides.

Vander Zalm told BIV that he initially wanted to sell the site in small chunks.

“I thought it should have been sold in blocks at different times to people locally. The breakup would have brought in more cash initially, but long term I think the decision [to sell the entire site to Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-shing] was OK. We did all right.”

(Former Premier Bill Vander Zalm stands next to his garden at his home in Ladner | Romila Barryman)

The BCEC board, headed by Brown, rejected the idea of selling separate pieces of the site. It embarked instead on a worldwide search to find the best prospective buyer for the entire site.

The board’s goal was to find a deep-pocketed bidder who could continue development regardless of economic downturns.

While early news reports said that about 20 groups expressed interest, the global search ended up with only one serious international bid: the victorious one from Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-shing and partners, who created Concord Pacific Developments.

Toigo connected with Jack Poole, who then headed BCE Development Corp., a real estate development subsidiary of telecommunications giant Bell Canada Enterprises.

The two planned to put together a bid to buy the entire site. But after stock markets crashed in October 1987, BCE pulled its financing for the bid.

Poole remained interested.

He left Toigo and joined with David Podmore, Concert Properties Ltd.’s current CEO, and assembled a consortium of what Podmore told BIV was about 10 local developers, including Peter Wall, Edgar Kaiser, Sam Belzberg, Charles Woodward, Robert Lee and Pattison, although Pattison told BIV he didn’t remember being part of the group.

The plan was for Poole’s consortium to finance 38% of the site’s purchase and raise the remaining 62% by selling shares to the public.

“That turned out to be the weak part of our bid,” Podmore said, “because Li Ka-shing’s bid was cash.”

Years previously, Podmore had been vice-president of planning, design and engineering for BC Place Corp., a role that saw him prepare a master plan for the site before Expo started. That plan guided the installation of sewers, utilities and other infrastructure for the fair and future urban developments.

It also mapped out locations for future residential towers. As a result of that plan, both Jack Poole’s consortium and Li Ka-shing’s group were essentially bidding on the same development plan, Podmore said.

Toigo, meanwhile, entertained the idea of bidding, and he went to Hong Kong to see Li Ka-shing’s representatives despite all bidders being bound to a confidentiality agreement. Because he was close to Vander Zalm, some feared that he would use that influence to insinuate himself into Li’s bid.

The trip spurred accusations of influence peddling, which prompted an RCMP investigation that cleared Vander Zalm of wrongdoing.

“[Selling the site] was a little controversial at times,” Vander Zalm told BIV. “There were those in cabinet who thought it should go to local developers. Then there were those who obviously thought, ‘No, We needed somebody from China or some other place that had deep pockets. That was the choice we were given.”

In the end, Concord Pacific paid $50 million up front and, over the course of a 15-year term, a total of $320 million. Bonuses would also be paid to the province depending on what zoning Vancouver city council approved.

Post-sale zoning

One of Concord Pacific’s early plans for its industrial site was to rezone the land as residential and have a series of condominium towers surrounded by moats with bridges to enable access.

“The city rejected that plan for two reasons,” said former city councillor Gordon Price.

“One is that the plan didn’t extend the downtown grid, so it seemed to be separate. The little islands would effectively turn into gated communities. The second reason was that the hydraulics didn’t work, and it wouldn’t work with the impacts from False Creek.”

City council at the time, however, was ecstatic that the entire site was sold in one piece and that the price was seen to be low, Price said, because it made it easier for city council to comprehensively rezone the site to create a new community. The low price for the site also allowed the city to extract more public benefits and amenities from Concord Pacific.

“It put the city in a very good negotiating position,” Price said, “if you could even call it negotiating.” •

Expo 86 site sale Timeline

March 1987:

Victoria creates BCEC as the owner of the Expo site and other government assets

October 15, 1987:

Grace McCarthy tells media that 20 developers have submitted their names for consideration in buying the Expo 86 site

October 19, 1987:

Global stock markets crash on what would become known as Black Monday

October 26, 1987:

BCE Development Corp. chairman Jack Poole says turmoil in markets could make it difficult to secure financing

December 8, 1987:

Premier Bill Vander Zalm says that the list of potential developers for the former Expo 86 site has been narrowed to seven: two from Canada; two from Hong Kong; and one each from Europe, Japan and the United States

February 15, 1988:

Top contenders on a short list were given this deadline to file detailed bids

March 28, 1988:

Media reports that Jack Poole’s new consortium bidding to buy the Expo 86 site include Jim Pattison, Edgar Kaiser, Sam Belzberg and Charles Woodward

March 30, 1988:

Vancouver Mayor Gordon Campbell stresses that city council will maintain firm control over the Expo site with bylaws and zoning after the new owner is announced and that a good price for the site would be $150 million

Early April 1988:

Developer Peter Toigo says he wants to spend $500 million to buy all of BCEC’s lands, which includes the Expo site and about 1,500 other hectares of property, including BC Place Stadium, the Vancouver Convention and Exhibition Centre and Lonsdale Quay

April 11, 1988:

New Democratic Party leader Mike Harcourt wants the Social Credit government to halt the sale of all lands owned by the BCEC and hold a public inquiry into the bidding process

April 16, 1988:

Peter Toigo terminates his efforts to buy all of BCEC assets

April 27, 1988:

A consortium headed by Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-shing wins the bid to buy most of the Expo site north and west of Science World for $320 million and intends to spend up to $2 billion developing the land over 20 years