On the same day the first commercial fishery of the season was expected to open for Nass River salmon, union leaders representing commercial fishermen and fish plant workers weren’t on the water or canning fish – they were in Ottawa asking the federal government to stop gutting the West Coast fishing industry.

Specifically, they were lobbying the parliamentary standing committee on fisheries and oceans to break what they describe as a monopoly held by Jim Pattison and his Canadian Fishing Co. (Canfisco) on fishing fleets, quotas and licences.

They also want the government to restrict the practice of sending fish caught in B.C. for secondary processing to the U.S. or China.

“The processing of fish that is owned by the people of Canada should benefit the people of Canada,” Arnie Nagey, a Haida citizen who worked as a millwright in Canfisco’s Prince Rupert cannery, told the committee June 7. “The boats should be owned by the people who fish them, not the company.”

Ken Hardie, Liberal MP for Fleetwood-Port Kells, sits on the committee. He told Business in Vancouver the committee had yet to hear from all the industry players, but he said he was struck by how different the commercial fisheries are on Canada’s west and east coasts. He said the way the fishery has evolved here “appears to have had a negative impact on the community-based fishery along the West Coast.

“On the surface, this impact will be amplified if, as the UFAW [United Fishermen and Allied Workers’ Union] claims, there is significant concentration of fishing licences in the hands of a company that also has the ability to shift fish processing from one community to another, across international borders.”

North coast fish plant workers want adjacency rules, which would require fish caught in Canadian waters to be processed in Canada.

But that would likely trigger challenges under the North American Free Trade Agreement, said Rob Morley, Canfisco’s vice-president of product and corporate development.

B.C. had adjaceny rules, he said, but they were successfully challenged by the U.S. under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the Free Trade Agreement.

“If we tried to put them in and anyone challenged them, we would lose,” Morley said, adding that all primary processing (gutting, for example) is done in B.C. “We process 100% of the fish that we catch in B.C. in B.C. We don’t process any of our B.C. fish in Alaska. On the other hand, we have brought Alaskan fish into B.C. for processing from time to time.”

But Canfisco will no longer can fish in B.C., although it will continue to can fish in Alaska, where it has three fish plants. Last year, the company announced it was shutting down its Prince Rupert cannery. It will still process salmon for the fresh fish market. There will be some work at the Prince Rupert plant, but not much.

“We usually have 750 on the seniority list,” Joy Thorkelson, the UFAW’s northern representative, told Business in Vancouver. “We don’t know how many people will be called back. The company was saying 350, but now they’re saying maybe only 200.”

The problem on both coasts is that more fish are being concentrated in corporate hands, Thorkelson said. She estimated that 40% of the salmon quotas in B.C. for the seine and troll fleets belong to Pattison and Canfisco.

But Morley said Canfisco owns 32% of 275 salmon seine licences, but no troll licences.

A quota system avoids a commercial opening’s derby fishing approach that results in too many boats chasing too few fish at the same time.

Thorkelson said the union recognizes that there may no longer be a market for canning salmon in B.C. But she said there is other processing that could be done in B.C. that is being outsourced to other countries, and she said too much quota has ended up concentrated in the hands of one company: Canfisco.

But Morley said the real problem in B.C. is that the commercial catch in B.C. has continued to fall over the decades, while Alaska’s commercial fishery has thrived.

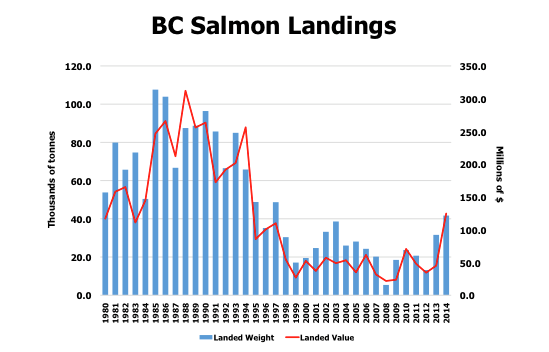

Since the 1980s, B.C.’s salmon production has fallen from an average of 150 million pounds per year to an average of 48 million pounds, Morley said.

The one thing Canfisco and commercial fishermen might agree on is that the decline in B.C.’s commercial fishery is largely a management policy issue.

On the West Coast, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) takes a much more conservative management approach than Alaska does. It also has obligations to First Nations. Ever since the Sparrow Supreme Court decision in 1990, DFO has been obliged to reduce the commercial catch to allow First Nations to take more fish. But it also has higher escapement targets.

Morley said Alaska allows 70% to 75% of salmon to be harvested by the commercial sector. In B.C., in a good year, commercial fishermen might be allowed to harvest 45% or 50%, he said.

“But that’s very unusual. In most years we’re harvesting a quarter of the fish.”

Alaska and B.C. also manage their salmon hatcheries differently. B.C.’s salmon hatcheries are run for the sport fishing sector; Alaska’s are run collectively by commercial fishermen. The returns are huge.

If the federal government wants to level the licensing and quota playing field, Morley said it should make commercial fishing licences bankable. A fishing licence can be valuable capital. But they’re treated as annual permits that can be cancelled at any time. Banks therefore don’t consider them secure and won’t lend fishermen the capital they need to buy quota or invest in their fishing boats.

“They try to maintain the fiction that the licences that these people have had for 40 years, and passed on from their parents, is an annual privilege that you can yank at any moment,” Morley said. “That needs to be changed. That’s the insecurity.”