Behind almost every advancement in Pablo Ruiz y Picasso’s artistic evolution stood a woman, inspiring him, driving his styles and colour palettes forward. While many of Picasso’s periods can be defined by the women in his life, however, the women should not solely be defined by the man.

Photographers, law students, star ballerinas... in examining the impact of his first loves, wives, introduction to fatherhood and infamous womanizing, the Vancouver Art Gallery has gathered some of Picasso’s most major works – paintings that altered the course of art history and continue to impact artists today – into Picasso: The Artist and His Muses (June 11-Oct. 2), the most significant Picasso exhibition ever presented in Vancouver.

There are more than 60 artworks from 38 international lenders present, including highlights like Bust of a Woman (Dora Maar) and the rarely exhibited Head of a Woman (Olga Kokhlova), with some of the most iconic works coming from the Picasso family themselves.

Created by Art Centre Basel and produced in collaboration with the VAG, we caught up with curator Katharina Beisiegel by phone in Switzerland to learn more about the women, the myth, and the legend.

Describe the show:

It’s an overview of Picasso’s work from 1906 to 1973, which are basically the most important years in his career. And I wanted to look at Picasso a little bit differently than other exhibitions have in the past by focusing on the women in his life. Working with Picasso, I realized that there are very interesting stories to be told about the women by his side, [who] had such a profound influence on his work and, sort of, shaped or even heralded the transformations in his work. Because he was such a prolific and diverse painter, it’s really interesting to see the development of his work and introduce the women behind these portraits.

Tell me about the women featured in the show?

We have Fernande Olivier, who was his first great love. And then his first wife, Olga Khokhlova, and then Marie-Thérèse Walter, who might be the most iconic muse that we know. She is the most well-known muse for all these sensual, erotic paintings that he did of her. Then of course Dora Maar, a well-known photographer and surrealist. And then Françoise Gilot, [and second wife Jacqueline Roque]. We have all these women, and they’re all so different. The only thing that seems to unite them is their love for Picasso and the creative relationships that they had with him.

When you put all these artworks together, what kind of changes can you see?

When he was still living in Spain, he was based in sort of a realistic, impressionistic style. And then he moved to Paris and you see the Blue Period, the very sombre tones. Everything is in blue and he’s painting the poor people of Paris that he was surrounded by. He was living in Le Bateau-Lavoir, this artist base where all these creative minds came together and lived in great, great poverty together but lived for the art.

Then meeting Fernande and falling in love with her, his entire colour palette changes. The blue tones are gone and we have this Rose Period, where he’s painting her in the south of Spain where they are on vacation. We see these dark ochre tones and reds and her voluptuous forms, and it becomes very sensual.

And then we’re moving on to Olga, who was a Russian ballet dancer, a ballet star. She was touring the world, and she fell in love with Picasso and she had these very classical features. We have a very realistic portrait of her, almost impressionist in style, and when you look at it maybe you wouldn’t even think it’s a Picasso. And then when you look at how his depictions of her change, his first son is born and you have this idea of motherhood, and it gets more abstract and more abstract, resulting in paintings that are very difficult to understand, because they are so abstract we don’t even recognize them as a portrait of a certain woman anymore.

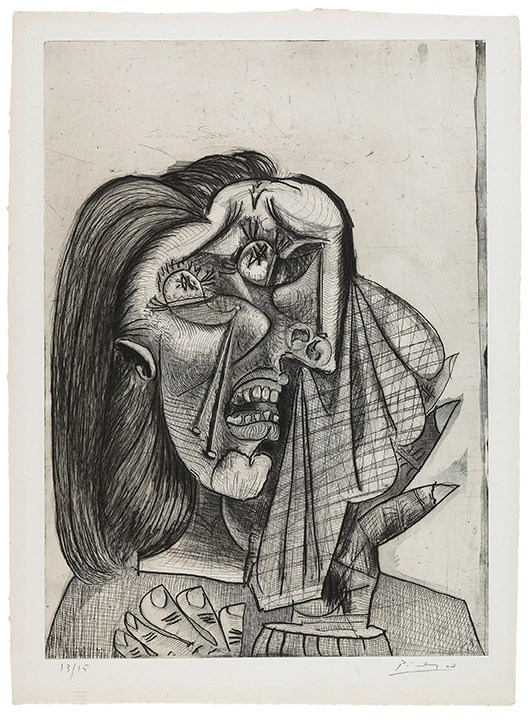

Pablo Picasso, Weeping Woman, 1937, etching, drypoint, engraving, and aquatint on laid paper. - National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa © Picasso Estate/SODRAC (2016)

Does this exhibition delve into his relationships with these women?

Yes, especially in the catalogue. […] It was very important to me to put a different focus on this [exhibition]. A lot of the legends that we know about Picasso have been put out there by his friends and the people that wrote about him, that knew him, and that was a very male dominated time. The ‘60s. And Picasso himself I think really enjoyed sort of the image of the macho [male].

But François Gilot was the only woman who stepped away from the relationship and left him, and was not left by him. Not being with Picasso always seemed to have quite an effect on the women, because he must have had a grand personality. If you were with Picasso it meant you became part of art history, you knew that there was this great artist painting you, and the women knew that when they were with him.

Can you share a story behind one of the paintings?

We can identify certain colours with certain periods, and for Françoise, La Femme-Fleur (Woman Flower), there is a lot of green and blue in the paintings, and there is a really interesting anecdote about this. Picasso was friends with Henri Matisse, and they were always, sort of, in this competitive state. Picasso had dinner with Françoise and Matisse, and Matisse was smitten with Françoise and said, “Oh, I’d love to paint you as a flower.” And then Picasso said, “No, I’m painting her as a flower.” [Laughs] And that’s how one of the most iconic paintings from that period came to be. I love that story. Of course, with all of the Picasso legends you have to take it with a grain of salt; I’m sure there’s some truth to it, though.

Speaking of legend, we’re seeing Picasso’s name everywhere right now, from Vanity Fair to Vancouver. Is he having a bit of a revival?

I hope so! [Laughs] He is probably one of the most important painters of classical modernism, if not the most important painter. And he had such a profound influence on art throughout his life, that even now we’re still seeing influences.

The way he approached painting was so different than anything that had been done before, and he was so versatile. You look at the variety of painting styles that he invented or that he painted in that no one had done before him and maybe no one has done since. With the exception, maybe, of Gerhard Richter.

What are some ways we are still seeing his influence?

He was not interested in developing one style and being known for that style. If you follow his portraiture, you have the feeling he was always looking for a certain quality, a certain essence, and it wasn’t based in a certain style. It’s really trying to adapt the style to his surroundings and the many influences he had.

This can be seen in his post-war style – after World War II he felt there was a necessity to find a different pictorial style after what the world had gone through. It was truly, for Europe, a new beginning, and he was looking for a way to express that in his art. And that is something a lot of contemporary artists now do, they feel that they have to reinvent themselves as an answer to what’s going on in the world.