(This is the second part of a three-part series on the British Columbia Wine Authority's plebiscite. Part 1: B.C. winery owners sour on having to join regulatory body); Part 3: Plebiscite result restricts non-BCVQA labelling)

The B.C. wine industry could soon become more lucrative.

That’s in part because B.C. winemakers will soon be allowed to put names of smaller regions on their bottles’ labels. The industry showed overwhelming support for the idea in a provincial plebiscite that the British Columbia Wine Authority (BCWA) held in May and June.

The goal of having more localized place names on bottles is to raise the prestige of B.C.’s wines and, in the process, revenue and profit for winemakers.

Consumers could also benefit from labels that make it easier to identify a wine that they want to drink.

The BCWA will have more authority to regulate what place names winery owners put on bottles, allowing it to reassure customers that the wine in the bottle genuinely comes from the region or sub-region mentioned on the label.

The wine world is filled with wine regions as well as smaller appellations.

The general rule of thumb is that wines that are identified as being from smaller specific areas are coveted by consumers and priced higher than wines that come from grapes grown in a much wider area.

A wine from France’s Bordeaux region, for example, is likely to attract higher prices than one identified more generically as a product of France.

Within Bordeaux are 54 sub-regions, or appellations, such as Saint-Émilion.

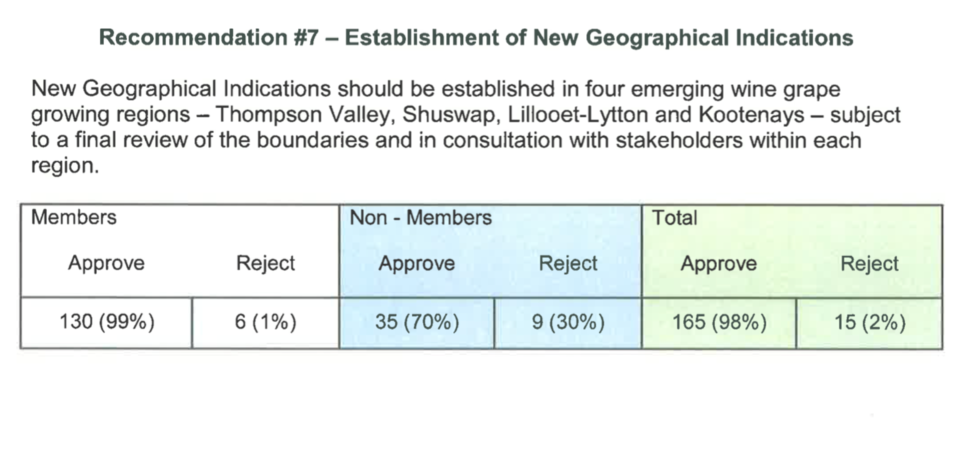

The first baby-step that the B.C. Wine Appellation Task Group wants to take is to allow winemakers in four parts of B.C. – the Thompson Valley, the Shuswap, Lillooet-Lytton and the Kootenays – to put those place names on bottles. Previously, they could only identify their wines as originating in B.C. and could not be more specific on the front label of their wine bottles.

The other five regions that winemakers can currently identify their wine by on labels are:

•the Okanagan;

•Similkameen Valley;

•Fraser Valley;

•the Gulf Islands; and,

•Vancouver Island.

(Image: the raw number indicates the number of winery owners voting in that category. The bracketed percentage is the voting percentage based on the volume of all B.C. wine. The plebiscite required a vote of 65% of winery owners in order to pass as well as a vote that represented winery owners who produce at least 50% of the total volume of B.C. wine)

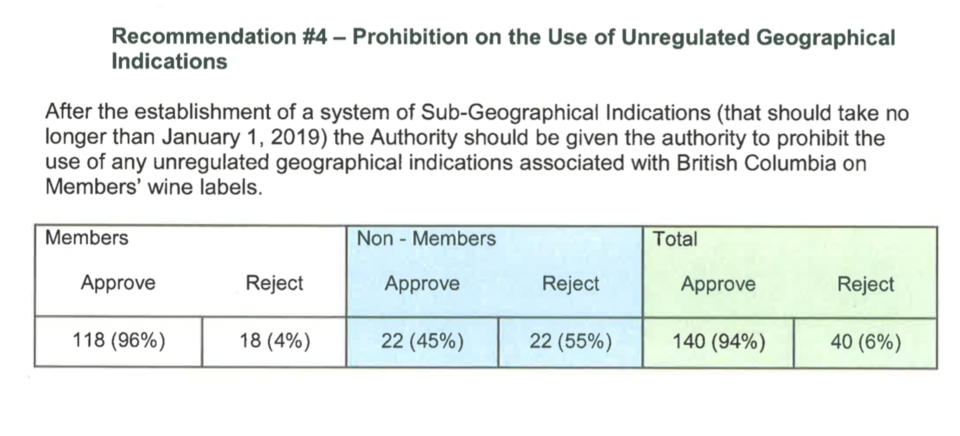

(Image: the raw number indicates the number of winery owners voting in that category. The bracketed percentage is the voting percentage based on the volume of all B.C. wine. The plebiscite required a vote of 65% of winery owners in order to pass as well as a vote that represented winery owners who produce at least 50% of the total volume of B.C. wine)

The second, bigger step the task group intends to take is to break these regions into smaller sub-regions that winemakers would be free to name on their labels.

Winemakers voted 92% in favour of allowing the four new geographic regions’ names to be put on labels and that support represented producers of 98% of B.C. wine.

Winery owners also voted 78% in favour of allowing the inclusion of sub-regions and having the BCWA regulate them. That total included producers of 94% of B.C. wine.

(Image: the raw number indicates the number of winery owners voting in that category. The bracketed percentage is the voting percentage based on the volume of all B.C. wine. The plebiscite required a vote of 65% of winery owners in order to pass as well as a vote that represented winery owners who produce at least 50% of the total volume of B.C. wine)

The plebiscite set a deadline of January 1, 2019, to create the boundaries and names of the sub-regions, although Mike Klassen, who is the task group’s executive director, said that date is only a guideline.

“For the time being, the focus will be on the Okanagan because it has the most mature viticultural regions,” he said.

Klassen’s group has already divided the Okanagan into 15 proposed sub-regions and winemakers voted 79% to accept that rough sketch as the basis for establishing the sub-regions.

Klassen noted that people in some parts of Vancouver Island also want to create sub-regions and that the process may stretch beyond 2019.

“It’s really up to the producers themselves,” Klassen said. “If there is a group of producers in the Cowichan Valley and they want to make a case through various established criteria around climate and terroir, they can apply for one.”

B.C. wine industry pioneer and task group member Harry McWatters explained to Business in Vancouver that the initial drawing of the sub-regions within the Okanagan Valley will resemble a cracked mirror in that the all borders are contiguous and no land is left without a regional name.

That is because if land were left out of being in one region, it would potentially be seen to have less value.

After the sub-geographical areas are named, generically, with reference to a town, village or other historical identifier, further splintering can take place.

McWatters explained that while the sub-regions within the Okanagan Valley have been delineated in part by regional characteristics, the future creation of official appellations will be carved out based on the science of the soil, the slope of the land and specific grape varietals that must be used.

That is why he does not want to call the current breakdown into sub-regions “appellations.”

B.C. has one appellation so far: the Golden Mile Bench. BIV reported on that when Victoria approved the move in March 2015.

Winemakers in that region went through a separate multi-year process to get the government to agree to create that appellation in 2014.

The recommended new sub-region that the task group has for the area that includes the Golden Mile Bench also includes some land that is outside the official appellation. •