Eight months after construction started on the Brock Commons student residence at the University of British Columbia, Brent Olund signed his name to the last of 464 giant panels of cross-laminated timber as it was secured into place on the 18th floor.

It was more than just a routine topping-out ritual for Olund and his firm, Urban One, who are construction managers at the UBC tall wood building project. Olund and the team members who signed with him on June 9 had just established a new world record. At 53 metres in height, Brock Commons is now the highest tall wood building on earth. And it was built in record time, thanks to new technologies that are transforming the way the world thinks about wood. Once construction began on the wood components, it took only nine weeks until the final cross-laminated timber (CLT) panel was fastened down, he said during a recent tour of the building.

“We completed 17 floors of structure and envelope,” said Olund, who is vice-president of construction at Urban One. “We managed to hit a timeline of two floors a week.”

On September 15, UBC marked the completion of the structural part of the building. It is expected to be ready for occupancy by next May, four months ahead of schedule.

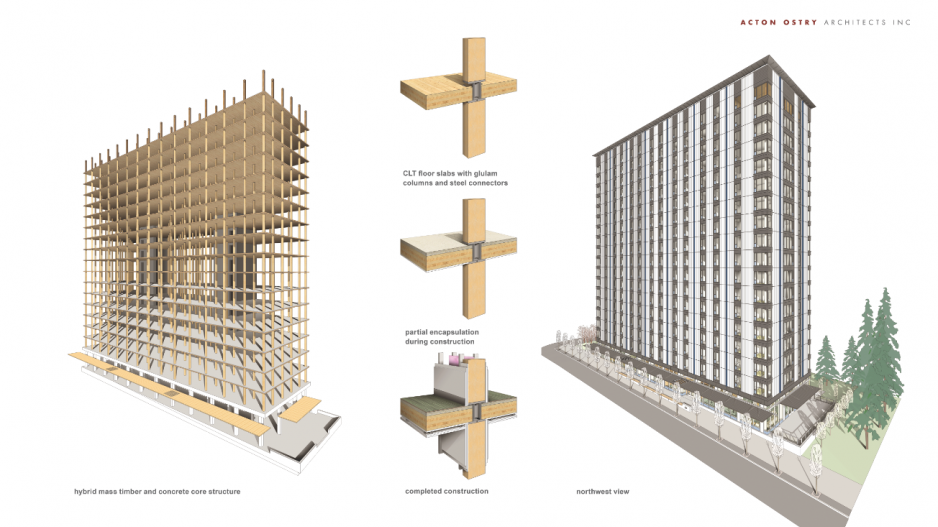

Brock Commons is a hybrid building, combining elements of concrete, wood, steel, and aluminum construction. The first floor is concrete, as are the elevator and stair towers. The rooms are framed with steel studs, the exterior facade is aluminum, and there is lots of glass.

But that’s where the similarity with every other highrise ends. Above the main floor are 17 storeys of large glue-laminated wood columns attached to floor slabs of CLT.

CLT is an engineered wood product that is like a massive, structurally stable sheet of plywood, but instead of being made from wafer-thin veneer, it is assembled by gluing together successive layers of structural lumber. At Brock Commons, the panels are five layers thick and 2.85 metres wide, and most are eight to 12 metres long. The largest panels weigh up to 3,500 kilograms each. They were prefabricated and assembled at the site like pieces of Lego, cutting down on costly construction time.

Brock Commons has put UBC in the lead worldwide in tall wood construction. John Metras, managing director of infrastructure development at the university, said UBC has taken to mass timber technology because it “aligns and contributes to UBC’s goals around sustainability and innovation.

“We think mass timber is a sustainable and cost-effective building material in the long run, so we think it is worth demonstrating that in a practical application.”

Brock Commons | Photo: Gord Hamilton

The $51.5 million structure is on budget, and Metras expects any future buildings to cost less, as the Brock Commons budget also includes $4.45 million from external agencies to cover first-time costs of using mass timber on such a scale.

UBC has several smaller buildings that use mass timbers, but the sheer size of Brock Commons, plus its use of CLT in combination with other materials in a highrise tower, marks a major step in the evolution towards a tall wood building that is all wood. The elevator and stairwell towers could have been made from CLT, Metras said. The research demonstrating it has already been done. But building codes and public acceptance of mass timber lag behind the research.

Fire is the main public concern, but issues like moisture and earthquakes also weight heavily on the public mind. Metras said the university has taken extra measures to ease those concerns. CLT is not flammable. It only chars when exposed to flames, even for a prolonged period of time. However, to increase the fire rating and to gain “social licence” from students and the public, the wood elements have all been covered by three layers of drywall, he said.

To learn more about other issues, like moisture content, vibration, and movement of the structural pieces, the building has been embedded with sensors. Civil engineering grad students will monitor its performance.

The cost per square foot, Olund said, came in slightly higher than concrete but much of that is attributable to first-time costs. Within five years, he speculated, mass timber buildings could be more economic than those made of concrete. Olund described himself as “agnostic” when it comes to preferences for building materials.

“For us, it comes down letting the materials each do what they do best structurally, and also letting the economics drive what happens.”

He said he expects research will prove that the added cost of wrapping the wood in drywall is unnecessary.

Metras admits that UBC’s decision to wrap the wood in three layers of drywall was a conservative approach, but added that there is one additional benefit. It is, after all, to be a student residence, he said. And students, being students, may have felt the urge to carve their initials into it.