A decision made 30 years ago this week in Switzerland meant Vancouver’s Expo 86 might have been North America’s last world exposition. It also meant the door was opened to a viable Olympic bid by the hockey-mad city and sport could become a global industry.

From Philadelphia 1876 to Vancouver 1986, 13 world expositions were held in North America. Countries were invited to showcase their innovation and share their cultures on a grand scale. The events were so big that in 1904, St. Louis hosted the Summer Olympics within its world’s fair.

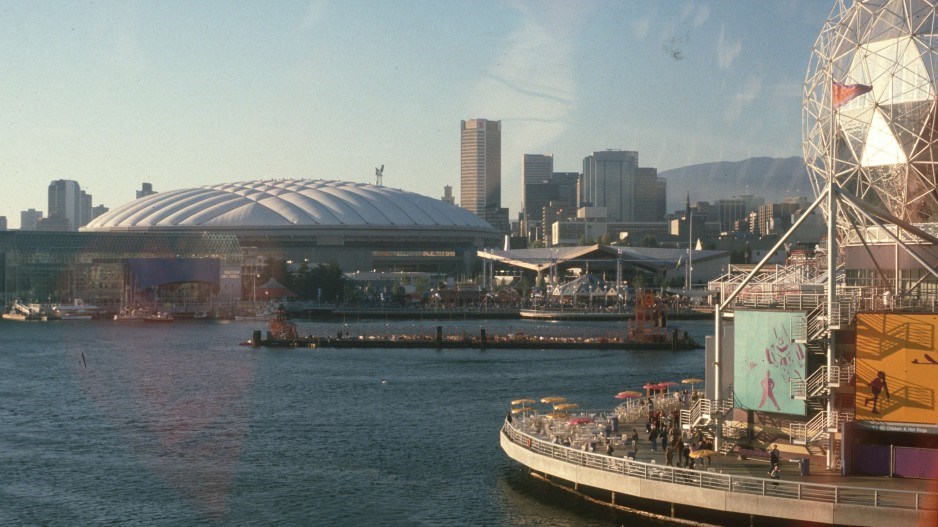

Vancouverites got a taste of the future from May 2-October 13, 1986, with rudimentary versions of the world wide web and a drone. But world’s fairs also needed years to build a city-within-a-city and took six months to stage. No wonder there has not been one on this continent since 1986.

Half a world away in Lausanne, Switzerland, the International Olympic Committee met, the same week Expo 86 closed, for its 91st general assembly to consider two issues which would turn the five-ring circus into a more lucrative spectacle than an exposition.

The Games had stubbornly clung to the ideals of amateurism, but president Juan Antonio Samaranch saw opportunity amid controversy. Western audiences had often complained that their best professionals were shut out of the Olympics while Soviet bloc governments were permitted to send athletes who were paid to train and play full-time.

Willi Daume, the organizer of the Munich 1972 Olympics, tabled a report that favoured letting professional athletes in. IOC members at the October 1986 session voted to allow most professional soccer players, all National Hockey Leaguers and many other professionals to compete. A decision on tennis players was delayed.

The IOC also decided that, beginning in 1994, the Winter Games would be held two years after each Summer Games. That decision allowed the Winter Games to grow and eventually rival the prominence of the Summer Games in key northern hemisphere TV markets. The Olympics were what world expositions were not: 17 days of non-stop, must-watch moments that left the viewer wanting more.

The U.S. sent its first Dream Team of National Basketball Association all-stars to Barcelona 1992. The NHL followed suit in 1998 for Nagano, but the Czech Republic ruined the party for both Canada and the U.S. However, later in 1998, ex-Vancouver Canucks’ owner Arthur Griffiths successfully gained the Canadian Olympic Committee’s endorsement for a bid by Vancouver and Whistler for the 2010 Games. The IOC agreed in 2003, and the Games were eventually built around an all-star tournament of NHLers, ending in a nail-biting Canadian win over the U.S. in one of the most-watched hockey games in history.

Big name pros meant more eyeballs and bigger invoices for advertisers.

Several decades earlier, CBS had been the first U.S. rights holder, paying $50,000 for the Squaw Valley 1960 Winter Olympics. By 1984, when Los Angeles hosted a Games nobody else wanted, ABC paid $225 million. More recently, NBC signed on for some $12 billion to broadcast and webcast the Games between 2011 and 2032.

The IOC’s global sponsors, under The Olympic Program, or TOP, banner, used to pay $100 million for each quadrennial. Now the going rate is $200 million. And they can’t even put their names on signs in the arenas, so they have to advertise on TV and set up world’s fair-quality pavilions in the host cities. Parts of Vancouver’s old Expo 86 site came back to life with corporate and government pavilions in February 2010.

Big broadcast and sponsorship dollars came with the pros. What also followed were the cons. A litany of bribery, corruption, match-fixing and doping scandals have shaken the sport industry, from the field of play to the boardroom.

After it decided against a blanket ban of all Russian athletes at Rio 2016, the IOC showed how it feared millennials and technology could erode its dominance as the world’s biggest party. It launched a new online channel and decided to let more pros into Tokyo 2020. Surfing, skateboarding and sport climbing will help Japan get more attention over 17 days than the four expos it held between 1970 and 2005.