B.C.’s largest honey producer is teaming with Surrey-based high-tech researchers at Simon Fraser University (SFU) to come up with better ways to monitor bee health.

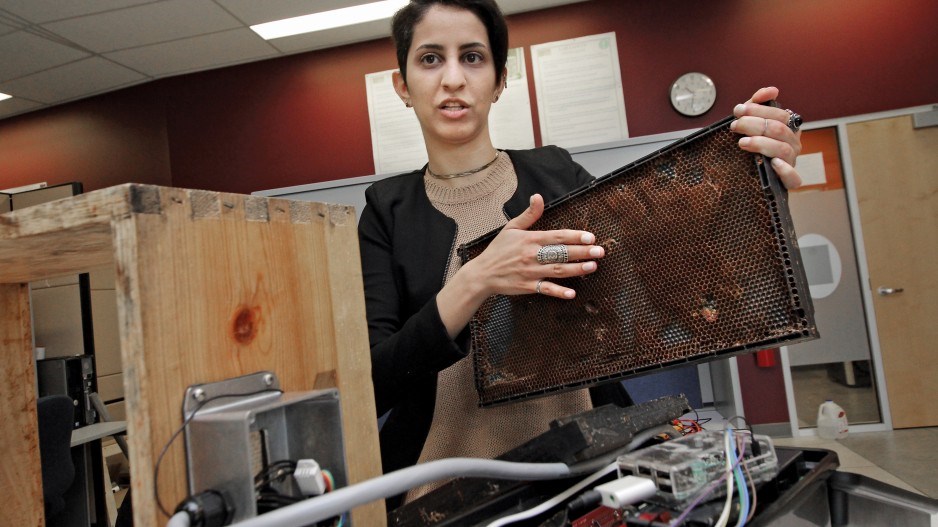

Oldooz Pooyanfar, a graduate student within SFU’s mechatronics systems engineering department, and Peter Awram, the owner and operator of Honeyview Farm, are developing new technology they hope can improve bee colony management.

Awram, who holds a PhD in microbiology from the University of British Columbia and did his post-doctoral work in virology and plant genetics at the University of Auckland, said the goal is to find less intrusive ways to track bee health.

“That’s one of the main problems with the bee research out there,” said Awram, whose honeybee farm is located in Rosedale. “Not that the scientists are poor, it’s just they don’t have the resources and the tools to look at numbers of hives that are statistically significant.”

Pooyanfar recently showcased the research’s progress at the Greater Vancouver Clean Technology Expo & Championship at Surrey City Hall. She’s creating tiny sensors with microphones and accelerometers that monitor sound, vibration, temperature and humidity.

“Using the data gathered and observing the condition of the hive, we want to train a neural network system that will recognize any abnormalities in the hive and let the beekeepers know,” Pooyanfar said. “This will help the beekeepers have a constant watch over their hives. And while it helps the beekeeper, it also prevents constant disturbance of the hive while the beekeepers open them to check their conditions.”

Awram noted that every time a hive is disturbed when it’s checked, it stops being productive for about 24 hours. He added that the research is important to sectors beyond just the honey industry.

“If you don’t have bees on your blueberries you don’t get any type of real crop,” he said. “The bees add a lot of value to the berries and the size.”

According to the British Columbia Blueberry Council, the province has more than 800 farmers over 11,300 hectares growing approximately 77 million kilograms of blueberries a season. This summer the provincial government announced the first full season of shipping blueberries to China in a trial run. The government estimates sales to China could amount to $65 million a year if the plan is fully implemented.

Awram noted B.C. is Canada’s biggest blueberry producer. According to statistics from the provincial government, the industry makes up 96% of Canadian production overall with $218 million worth of exports in 2015. To have bees monitored as closely as livestock, which are bred and managed for efficiency, could even further expand market potential, he added.

“Bees don’t have a mother and a father,” said Awram. “When you look at a bee, you have to look at the whole hive and the 20,000 to 30,000 bees in it. It’s the organism that you’re breeding, so it’s not like an individual cow.”

In July Vancity released a report by SFU biological sciences professor Mark Winston, who has been studying bees for 40 years and is the author of Bee Time: Lessons from the Hive, winner of the 2015 Governor General’s Literary Award for non-fiction. In it he estimates B.C. honeybees generate close to $500 million in economic activity through pollination and increased crop yields.

“Our fate is entangled with the bees,” said Winston in a recent interview with Business in Vancouver. “We depend on honeybees and wild bees to pollinate our crops, almost $600 billion in global annual value. And without bees most of the fruits, berries, vegetables and oilseed crops we depend on simply wouldn’t exist.”