In February, the province’s oil and gas ministry held its monthly drilling rights auction. For the first time in history, it walked away empty handed.

The $0 land sale kicked off a year of bad news for the industry. Critics took it as another death knell for the B.C. government’s dream of liquefying northeast gas reserves for export to Asia. With oil and gas prices stubbornly low after one of the worst downturns in history, multiple LNG joint ventures shelved or delayed projects. The dozen or so remaining proposals hang in limbo—waiting on government approvals and facing varying degrees of local opposition. Report after report suggested B.C. had missed its window of opportunity—that there’s just too much gas on the world market for B.C. projects to make money.

It seemed there was nothing but bad news for B.C. LNG in 2016. Until there wasn’t.

Despite the bruising it took this year, B.C.’s nascent LNG industry will go into 2017 with a positive investment decision and forward momentum on projects that had been written off a year earlier. Proponents have already spent billions advancing their projects through the regulatory processes and proving up gas reserves. While the province won’t meet its goal of three operating LNG plants by 2020 (short of divine intervention), Premier Christy Clark will be able to claim LNG is on track going into the 2017 provincial election, despite a few speed bumps.

Pacific NorthWest LNG, the Petronas-backed proposal near Prince Rupert, dominated the headlines in 2016. In March, Environment Minister Catherine McKenna delayed environmental approval of the $11.4 billion terminal to request more information on its impact on marine eelgrass beds. The project’s emissions are another concern: while supporters say LNG will offset dirtier burning coal in Asian markets, environmental groups say the terminal itself will be one of Canada’s largest emitters of greenhouse gases.

The project is pivotal for the Canadian oil and gas industry. With the U.S. quickly becoming self-sufficient in oil and gas production, Canadian producers risk being shut out of their largest market. Projections for the B.C. LNG industry have dimmed considerably since the B.C. Liberal government unveiled its LNG strategy in 2012. LNG supporters once talked of trillion-dollar prosperity funds generated from LNG revenue; now, many simply want to save the industry from terminal decline.

For struggling oilfield workers in Northeast B.C., the Pacific NorthWest delay was the last straw. Since late 2014, hundreds of people in Dawson Creek, Fort St. John and Fort Nelson have lost jobs as energy companies slashed exploration budgets. The region’s unemployment rate reached double-digits, while employment insurance claims and vacancy rates soared. A new market for natural gas was reason for hope.

In March, a group calling itself Fort St. John for LNG launched a truck rally, largely made up of equipment left sitting idle since the downturn. Hundreds of trucks lined up across the city to push the government to approve Pacific NorthWest.

While they waited, the bad news continued to roll in.

In July, Shell announced it was delaying its LNG Canada project near Kitimat. Just months before, Douglas Channel LNG became the first to formally bow out of the race. American LNG continued to stream out of the newly-built Sabine Pass terminal in Louisiana, supplying an already flooded market. In a sign of how dire things were on the LNG file, The Tyee reported provincial bureaucrats asked to play up good news stories about the industry had come up mostly empty. Peace Region politicians began to look for a Plan B.

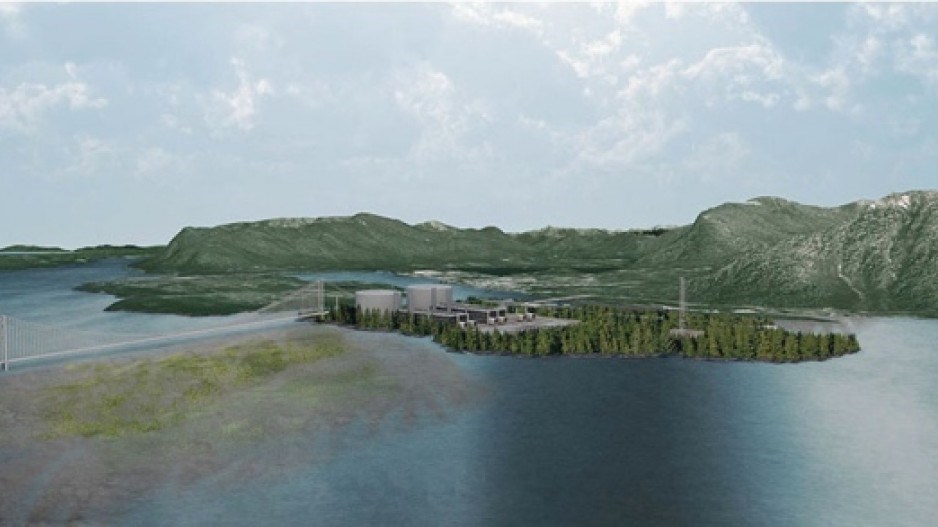

And then, in the early fall, three Trudeau ministers flew to the West Coast, found a patch of oceanfront by YVR and conditionally approved Pacific NorthWest LNG. A little over a month later, Woodfibre LNG announced it would build its project near Squamish (albeit only with a BC Hydro rate discount), the first project to go ahead. Both proposals continue to face hurdles, but going into 2017, the pall that has hung over the LNG file has lifted somewhat.

Questions remain over when Pacific NorthWest LNG will make its final investment decision, and whether it will come before or after the provincial election in May. There’s also the looming question mark of the Trump presidency and a cabinet that’s gung-ho toward U.S. oil and gas production.

Still, after a bruising year, B.C. LNG can’t be counted out. 2017 promises to be even more interesting for LNG watchers.