The hydrogen fuel cell car, which has been promised since the 1990s, is finally here.

Well, sort of.

Toyota (NYSE:TM) and Hyundai (Nasdaq:HYMTF) have both recently rolled out new hydrogen fuel cell cars, but getting one is a bit like adopting a child: there are forms to fill out, wait-lists to sign up for.

High costs and a lack of hydrogen fuelling infrastructure means the car of the future is still somewhat stuck in the future.

Recognizing this, Ballard Power Systems (TSX:BLD) switched focus several years ago from consumer vehicles to other applications, including a transportation niche that doesn’t require a national fuelling infrastructure: buses. In 2008, it spun off its automotive fuel cell division, which was acquired by the Daimler-Ford co-operative, the Automotive Fuel Cell Cooperation (AFCC).

Those two companies continue to make Vancouver a major hydrogen fuel cell innovation hub that has helped spawn a number of new players, including Greenlight Innovation, which, among other things, has recently developed a turnkey hydrogen fuelling station.

“B.C. is kind of known as the cradle of fuel cell development, starting with Ballard, so since then a lot of other companies sprung up as a result of Ballard,” said Carolyn Bailey, executive director for the Canadian Hydrogen Fuel Cell Association.

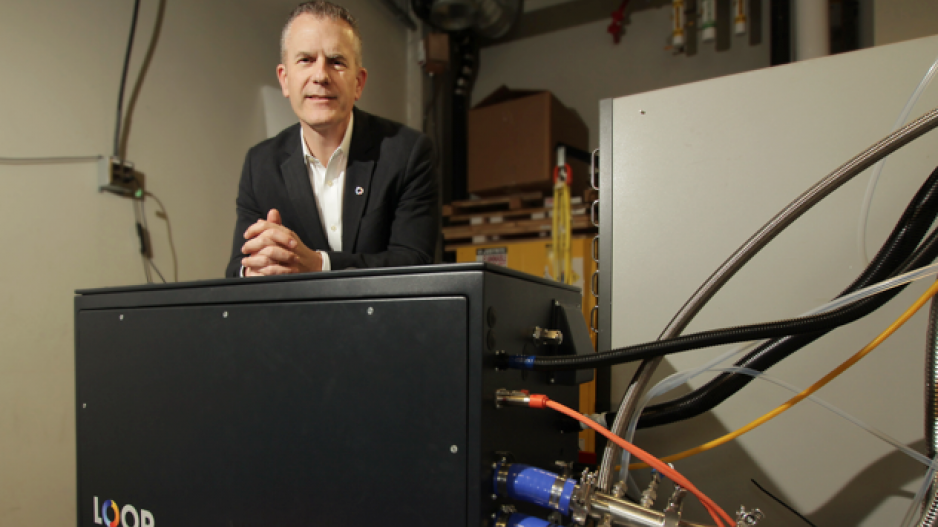

The newest kid on the block in Vancouver’s hydrogen fuel cell space is Loop Energy. Like Ballard, it is focusing on a niche market: heavy truck fleets used in ports and distribution centres.

Loop Energy isn’t really new – it has just flown under the radar for the last couple of decades.

Founded in 2000 by David Leger, who invented Loop Energy’s

eFlow fuel cell, the company has been quietly working out of the National Research Council’s (NRC) Institute for Fuel Cell Innovation at the University of British Columbia to develop what Loop CEO Ben Nyland calls the “hydrogen fuel cell 2.0.”

Last year, it moved off campus to its own office, and now it’s ready to make a splash.

“We’ve solved the economics, and that’s what’s been holding the fuel cell industry back,” Nyland said.

Earlier this year, Loop landed $7.5 million in funding from Sustainable Development Technology Canada (SDTC) to help it ramp up to commercialization, and it has entered partnerships with two big players in the heavy truck sector – Peterbilt and China National Heavy Duty Truck Group – to develop demonstration vehicles.

Loop Energy has, to date, been backed by a number of high-net-worth angel investors and has attracted some serious talent in the fuel cell space, including chairman Andreas Truckenbrodt, the AFCC’s former CEO; chief scientist Sean MacKinnon, a former NRC scientist; and former Ballard and AFCC program manager Rob Wingrove.

Hydrogen fuel cells generate electricity with zero carbon emissions by combining pure hydrogen with a flow of air, which is 20% oxygen. As the hydrogen and oxygen pass through a special membrane, they combine into water. In the process, a steady stream of electrons (electricity) is produced. But the problem with current fuel cell design is that, as the oxygen gets used up, electricity production falls. That’s the pain point Loop Energy says it has solved.

“It creates what you might think of, in simple terms, as an imbalance in the fuel cell,” Nyland explained. “What you need to do to accommodate for that, in a traditional fuel cell, is you just use more materials. So you build a bigger fuel cell that generates the right amount of electricity.”

Loop’s eFlow technology improves airflow in the fuel cell.

“Because eFlow balances the oxygen distribution in the system, we have the ability to remove between 30% and 40% of the materials that would normally need to be included in a fuel cell system,” Nyland said. “So it drops the capital costs by a substantial amount.”

The new design makes fuel cells competitive with diesel engines, Nyland said – a claim Peterbilt was initially skeptical about, when Loop approached the company to put its fuel cells into trucks.

“Peterbilt was very skeptical about fuel cells and ducked us for a while. Peterbilt did a deep dive on our economic model and, three weeks after that conversation, joined us to propose to SDTC that we together build a zero-emissions truck.”

As for markets, Loop decided to focus on a niche: “yard trucks” used in ports and distribution centres. The large, heavy-duty trucks travel short distances, ferrying containers within ports or from ports to distribution centres.

“The Port of Los Angeles is an example,” Nyland said. “There are 1,500 yard trucks operating in the port, just shunting containers around the port to different locations.”

Because the yard trucks don’t travel great distances, a limited number of hydrogen fuelling stations need to be built – fuelling infrastructure being one of the biggest challenges to wider adoption of fuel cell vehicles.

Loop and Peterbilt will start building a demonstration truck in February. The plan is to have the first demonstration vehicle in operation at a port somewhere by 2017’s second quarter.