Population growth, densification and an increase in cycling has made many Metro Vancouver intersections more dangerous, prompting city planners to turn to civil engineering for solutions.

Successful strategies are often replicated, as is the case at two of the city’s most dangerous intersections.

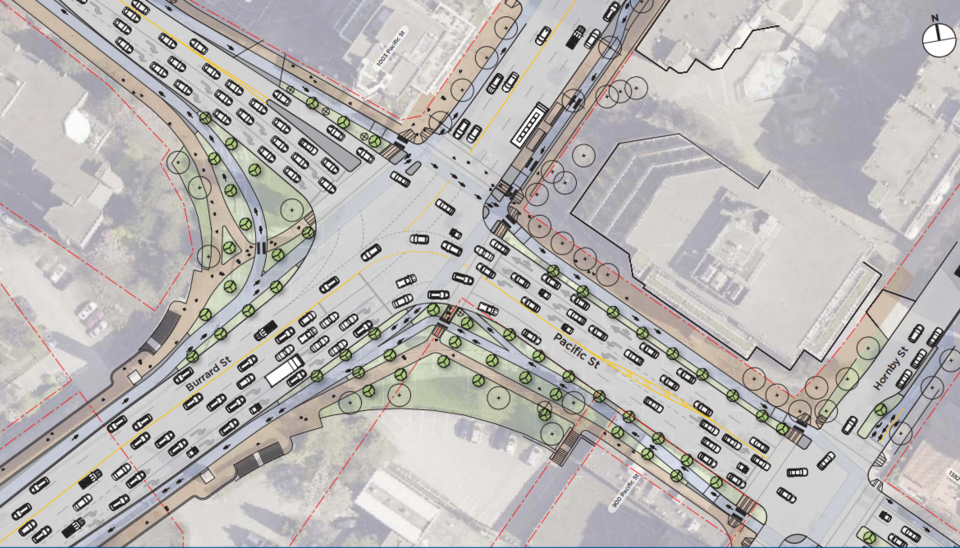

A similar solution will be employed in the next year at the north end of the Burrard Bridge and at Marine Drive and Knight Street, City of Vancouver director of transportation Lon LaClaire told Business in Vancouver.

“The collision type is the same,” he said, “and our solution is the same: to widen the exit lane to two lanes and signalize it so we don’t have people making poor decisions on when to enter traffic and forcing other people to do last-minute lane changes.”

Work at the west side of the intersection at Burrard Bridge’s north end is largely complete. Gone is the single lane that used to provide access for drivers merging into southbound traffic on the bridge.

Instead, Pacific Boulevard continues with two lanes that allow vehicles to turn right onto the bridge when there is a green light.

Vehicles heading eastward on Pacific Boulevard across Burrard Street will have only one lane.

“The Burrard and Pacific intersection was a big concern because it is the city’s second-highest collision location,” LaClaire said. “Worse yet is that a lot of the collisions involve cyclists and pedestrians because the number of those are so high. When they are involved in collisions, they get hurt because of their vulnerability.”

Far fewer pedestrians or cyclists are at Marine and Knight, but the solution was essentially the same.

(Image: Here is a rendering of the changes to the intersection at Burrard Street and Pacific Boulevard | City of Vancouver)

Instead of allowing one lane off the Knight Street Bridge for drivers merging with eastbound traffic on Marine Drive, there will be two lanes going east and traffic will be regulated with a light.

The Marine Drive and Knight Street work is slated to start later this year. Council approved the $1.5 million redesign last year.

The Burrard Bridge intersection revamp is a small part of the entire bridge’s $35 million makeover that is set to be complete by mid-2018.

Graham Infrastructure is leading the bridge rebuilding while the project manager is Associated Engineering and the Iredale Group provides architectural support to the project.

Work began in spring 2016, after the city’s Burrard Bridge project manager, David Currie, started working with University of British Columbia civil engineering professor Tarek Sayed, who conducted video analytics to determine what the traffic-flow problem was.

(Image: Construction on Burrard Bridge is relatively complete on the west side and is ongoing on the east side of the bridge | Rob Kruyt)

One of the more controversial aspects of the Burrard Bridge redevelopment project is the suicide-prevention fencing that will rise from new concrete railings along the structure.

Coun. George Affleck has questioned the fencing’s $3.5 million price tag, arguing that the money could be better spent on other city needs and that the fencing would obstruct the bridge’s beautiful views.

LaClaire admitted that he feared the fencing would not be very attractive, but he said that with the west-side fencing now in place, it looks “surprisingly good.”

The fence design still allows passersby views of the Burrard Inlet, and at the same time provides a physical barrier to thwart would-be suicide jumpers.

“We worked through a committee format that included the people who were experts at means prevention, or suicide jumpers, as well as architects and heritage consultants,” LaClaire said.

“Having them all in a room meant that we were meeting the need of [suicide] prevention in a way that was very sensitive to the architecture of the bridge.”

The new outer railings also have new pedestrian lamps atop concrete pillars that rise up at intervals from the concrete on the lower outer fencing.

Heritage-style street lights stand on the pedestrian pathway and illuminate the bridge itself.

(Image: The Burrard Bridge has restored lamp posts for the pedestrian footpath that were removed in the 1970s | Glen Korstrom)

During a bridge retrofit in the 1970s, the pedestrian lighting was removed from the bridge and traditional street lights were installed in place, using the same electrical wiring.

The new lighting adds more light for pedestrians as well as drivers.

The other controversial element of the bridge design was to remove one of the three northbound lanes so that cyclists can drive on the road on the east side and pedestrians can once again use the eastern sidewalk.

Heavy concrete pillars will separate vehicle traffic from the bike lanes.

The total weight on the bridge, however, is not likely to change much despite the pillars and the new metal fencing because with one less lane of traffic, there will be fewer cars on the bridge.

The bridge is strong enough to hold cars lined up the length of the bridge on six lanes. With only four lanes designated for vehicle traffic, there is more than enough capacity for the added weight, LaClaire said. •