This is Part 2 of a two-part series.

Part 1 focused on why the B.C. government changed the law to make it easier to wind up strata corporations and what the result has been. To read that, click here.

When the B.C. government changed the law last year to make it easier for condominium owners to group together to sell their complexes, it inadvertently gave life to a second, and controversial, method of selling homes.

While owners in dozens of condominium complexes across Metro Vancouver are using the new Bill 40 process to wind up their strata corporations, many others are grouping together to sell chunks of buildings – perhaps 60% or less – in a method of selling known as a unit assembly.

Bill 40 changed the Strata Property Act so that condominium owners could seek BC Supreme Court approval to wind up a strata corporation when 80% of all owners vote for that action in a meeting.

Any owner who does not vote is deemed to oppose the move, so achieving an 80% vote in favour of selling remains a significant hurdle.

Before Bill 40 came into effect, the court required unanimity unless extraordinary factors were at play. The result was a mere trickle of cases involving larger strata corporations petitioning for approval to wind up.

Indeed, it was so hard to get universal agreement that a British Columbia Law Institute (BCLI) report, which urged the government to create Bill 40, noted that between September 2011 and December 2013 there were 29 applications to terminate a strata corporation in B.C., and most were duplexes. Only four of those cases involved projects with more than 10 units.

In most situations, larger strata corporations simply paid for repairs and did not try to market their buildings to developers, the report noted.

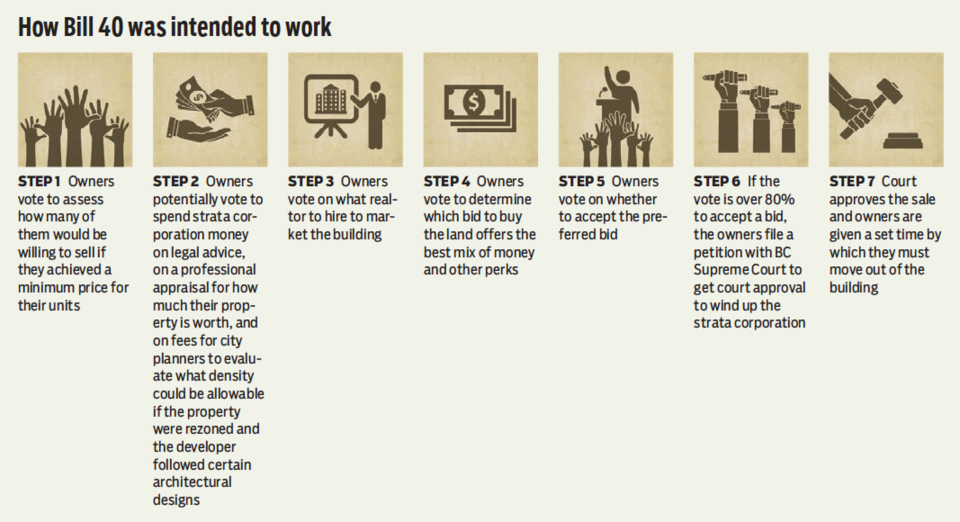

The envisaged process

The process that the BCLI report envisaged when it encouraged the government to draft Bill 40 and make it easier for condominium owners to sell buildings was to have owners work together each step of the way.

First, owners would vote to assess how many of them would be willing to sell.

If a significant percentage were interested, there could be a vote on whether to spend strata corporation money to pay for a professional appraisal of the property.

Strata funds could also pay for city planners to evaluate what density could be allowable if the property were rezoned, and if a developer were to follow certain architectural designs.

The Bill 40 report also envisaged that stratas would vote to select realtors and lawyers for the sale.

After the realtor had marketed the property to potential buyers and collected bids, he or she would present those offers to the strata corporation membership to determine the preferred option.

Factors other than money could push a low bid above higher offers. For example, one developer might let owners live in their units rent-free for a year and allow them to get discounted prices on units in any new development that rises on the site.

Once the strata corporation had selected what its members viewed as the best bid, its members would vote on whether they wanted to accept it.

This is where the 80% threshold kicks in.

The motion to dissolve the strata would simultaneously include hiring a liquidator, who would transform each owner’s ownership stake from, say, full title to one out of 100 units into one share in a legal entity that has 100 shares.

That new single legal entity would then be sold to a developer for the set price, and the proceeds would be divided among the owners in one of several ways, depending on when the condominium building was built.

Unintended consequences

One unintended effect of the government’s new law is that there has been a rise in unit assembly attempts. Brokers are marketing blocks of units to developers.

The government had expected that owners would work together as a cohesive block until 80% of owners agreed at a meeting to sell the entire building and that only then would any of the owners sign contracts to sell their units.

That expectation seemed reasonable because developers usually want to own a controlling stake in a building and not a collection of individual units to rent out.

“Generally, owning individual units is not our cup of tea,” said Houtan Rafii, vice-president of residential development at Beedie Development Group. “There are many projects currently being marketed that do not have agreement from 80% of the owners. There could be a block of 40 units or whatever. That doesn’t really interest us. We’ll look at it but when it comes time to put pen to paper, we’ve generally bowed out.”

However, other developers are more amenable to buying units in buildings.

Westbank and Bosa Properties were each accumulating individual units at 1075 Barclay Street in 2015 and 2016, before Bill 40 officially became law.

Bosa had already bought buildings across the street, and it was keen to buy units in the area between Thurlow and Burrard streets, partly because of the West End Community Plan, which was approved in 2013. That plan significantly raised allowable building heights between those two streets, which is where 1075 Barclay Street is located, to around 170 metres.

One developer in 2015 offered the 1075 Barclay Street strata corporation twice the previous year’s assessed value to buy the building. It then withdrew that offer within 24 hours, as owners were considering it, said Valerie Prodanuk, who is an owner in the building.

Excitement among owners was palpable because many started to believe that their homes could sell for much more than twice the assessed value. Months later, and one block south, Wall Financial Corp. sold a site at 1059 and 1075 Nelson Street to Sun Commercial Real Estate for $60 million. That was more than 3.8 times the land’s $15.6 million assessed value.

Sun then flipped the site to Chinese immigrant Gao Shan for $68 million in February 2016, according to an April 2016 article in the South China Morning Post.

Meanwhile at 1075 Barclay Street, owners held meetings and sought legal advice to determine options for how to sell the building. The consensus was for all owners to behave autonomously, instead of as a group, and list units individually with Royal LePage Sussex Klein Group principal Eugen Klein.

(Image: 1075 Barclay Street is on the northwest corner of Thurlow and Barclay streets and is in a one-block stretch between Thurlow and Burrard streets where density soared as a result of the West End Community Plan | Rob Kruyt)

Klein told Business in Vancouver that, in April 2016, he signed listing agreements with people who owned 75% of the suites, or 27 of the 36 units.

Eight more condominium owners later signed with Klein to become part of the assembly, and Westbank successfully bid to buy all of those 35 units.

Westbank is in “active negotiations” with the single holdout to buy the final unit, Klein told BIV. If Westbank reaches an agreement with that owner, it will be able to avoid the cost, risk and hassle of going to court because it will own all units.

“There was quite a bit of back-and-forth negotiation, and it’s not like everyone got the same price per square foot,” said Prodanuk, who received more than twice her unit’s assessed value in a sale that closed in January.

Klein’s firm is now marketing more than a dozen unit assemblies across Metro Vancouver. He also pitches his services to strata corporations at meetings about four to six times per month.

“Unit assemblies make sense when owners don’t want to pay an upfront legal cost,” he said.

Klein’s company pays all initial costs – legal, property evaluation and other fees – when it markets blocks of units in stratified buildings.

He collects his commission only when sales take place.

“Owners also may not want to go to court,” Klein said, touching on another difference between a Bill 40 windup of a strata corporation and a unit assembly sale.

(Image: Taylorwood Place, at the corner of Taylor Way and Keith Road in West Vancouver, is comprised of 21 single-family homes as well as common property and, as such, has a strata corporation | Google Street View)

With the Bill 40 windup method of selling, after a developer agrees to buy the site, the potential sale must be approved by a BC Supreme Court judge, who takes into consideration whether the sale will inflict an undue hardship on the owners who do not want to sell. No case has yet been approved by a judge and the first case was in court briefly yesterday before being adjourned to be heard on March 27.

That process takes time and delays the eventual payout for the owners.

Were the owners to sell via a unit assembly, the developer would simply buy each individual unit and pay the owners.

It would then be up to the developer to go to court once it owned at least 80% of the units to seek a windup under Bill 40.

If the unit assembly is less than 80%, the developer may wait to buy units as they come available.

Klein has a second unit-assembly project – Taylorwood Place, at the corner of Taylor Way and Keith Road in West Vancouver – in which he has sold more than 80% of the homes. He started marketing that project in 2013, when more than 80% of the owners agreed to list with him. The joint venture Taylorwood Investments Ltd., which includes Asian investors and a local developer, has agreed to buy 18 of the development’s 21 detached homes.

(Image: West Vancouver's Taylorwood Place has 21 single-family homes whose owners also own a share in common facilities such as tennis courts | Chung Chow)

The homes are detached single-family houses that share some common buildings, a pool, tennis court and other facilities.

Klein is working to try to get the three holdouts to also agree to sell their homes to Taylorwood Investments as that would help Taylorwood avoid court.

| Click here to listen to reporter Glen Korstrom on BIV on Roundhouse Radio discuss the impact of Bill 40 on stratified building sales. Discussion starts at the 15-minute mark. |

Brokers urge caution

Klein is rare in the Vancouver real estate market in that he sells real estate both as unit assemblies and as projects that have gone through Bill 40-style votes and obtained support for a sale from at least 80% of owners.

Brokers at large commercial firms that market Bill 40 windups say unit assemblies are a recipe for disaster.

Jim Szabo, vice-chairman of CBRE’s investment properties group, said his company is not involved in marketing unit assemblies within condominium buildings because those sales have a “low probability” of success.

That is because developers will not want to go to court to try to get approval to force a small minority of homeowners to sell, he said.

“These are large developers doing the buying, and they don’t need to have their names dragged through the mud with accusations that they are throwing people out of their homes,” Szabo said. “There are easier deals out there. Why go through that brain damage?”

(Image: Jim Szabo, vice-chairman of CBRE's investment properties group, believes that unit assemblies in condominium buildings have a "low probability" of success | CBRE)

Macdonald Commercial Real Estate Services similarly recently advised owners of several strata corporations to use “extreme caution” when deciding whether to embark on the unit-assembly method of selling.

Going that route could lead to fractured strata corporations, infighting, legal disputes between owners and developers, strata corporation bankruptcy or a single developer gaining partial control and making it difficult to get top dollar for the building on the open market, according to Macdonald Commercial’s letter.

Hart Buck, a vice-president in the Vancouver office of Colliers International, called Klein a “cowboy” for embracing the process of marketing larger unit-assembly projects in Vancouver condominium towers.

Buck added that he thinks going that route is “ridiculous” and should be “criminal.”

Buck said the unit-assembly method creates animosity among owners, and, because “you’re taking one part of one process and a piece of another process,” the initiative is likely to fail in court.

“If I was an owner in the 20%, I would stand up and say, ‘This isn’t a fair process because the building has never been marketed under this Bill 40 sequence,’” Buck said.

“Going through the Bill 40 process, the whole program is laid out and there’s a sequence of events that get you to the goal line. The assembly process is a shit show out of the gate, and if anything goes sideways, there is no legislation to say what you do.”

Klein defended unit assemblies, saying that when he markets large blocks of units in buildings, he is up front with potential buyers that he does not represent all of the owners. He warns potential buyers of unit assemblies that comprise less than 80% of a building that the buyer may not be able to persuade those who own remaining units to sell.

Klein also warns buyers that, even if they are able to own more than 80% of the building, they may not be able to persuade a judge to approve the entire building’s sale. •

This is Part 2 of a two-part series. Part 1 focuses on why the B.C. government changed the law to make stratified buildings easier to sell. To read that piece, click here.