John Plourde has resigned himself to the idea that the Morrison copper-gold mine his company wanted to build near Smithers probably won’t go ahead.

But he’s not going to go away quietly.

Plourde, CEO of Pacific Booker Minerals Inc. (TSX-V:BKM), has been sending stacks of court documents to reporters, in the hope that the “sham” process (a BC Supreme Court judge’s words, not his) that his company was forced to go through will be made public.

He doesn’t expect having his story told will persuade the provincial government to reconsider its rejection of the Morrison Lake project. He simply hopes his company’s travails become a provincial election issue and a warning to his peers in the junior exploration and mining sectors.

“I’m not asking anybody to do anything,” he told Business in Vancouver. “I’ve got no recourse. I went to court and the court reversed the decision, and I’ve got nowhere to go but to fight during the election. What they did is wrong. What they did is totally wrong.”

What “they” did is move the goalposts in the final stages of an Environmental Assessment Office (EAO) review, according to court documents.

Plourde isn’t the only one making that claim. So is the now-insolvent Compliance Energy Corp.

Earlier this month, Compliance filed a civil suit against provincial and federal governments for moving the goalposts during an environmental review of the Raven coal mine project on Vancouver Island, alleging procedural misfeasance and negligence.

The company claims it spent $20 million going through an environmental review and met all conditions, but was rejected due to “unknown changes in political policies.”

A sudden change in policy by the Ministry of Environment also appears to be behind the B.C. government’s rejection of Pacific Booker’s Morrison Lake copper-gold mine.

Pacific Booker spent $10 million and several years trying to get its mine through the EAO review process, only to be told that, despite meeting all the requirements, the mine would not be approved.

On October 1, 2012, former B.C. environment minister Terry Lake denied an environmental certificate for the project. Lake said there were too many uncertainties over the potential effects on salmon in the headwaters of the Skeena River system to approve the project.

“We ordered the further assessment because we concluded that the information currently available does not provide us with a sufficient level of confidence that the mine’s design can adequately protect the environment,” Environment Minister Mary Polak said in a written statement to BIV.

The company went to court, which ruled in the company’s favour, quashing the decision and ordering the ministries of Environment and Energy and Mines to reconsider the project.

Justice Kenneth Affleck ruled the environment minister’s decision “failed to comport with the requirements of procedural fairness.” In summing up the company’s view, the judge used the word “sham” and talked about moving goalposts.

Even one of the Liberal government’s own MLAs, Ralph Sultan (West Vancouver-Capilano) weighed in on Pacific Booker’s behalf.

Responding to government representatives who characterized Pacific Booker as too small to have the financial wherewithal to live up to commitments and requirements of an EAO certificate, Sultan wrote Lake’s successor, Polak, in Pacific Booker’s defence.

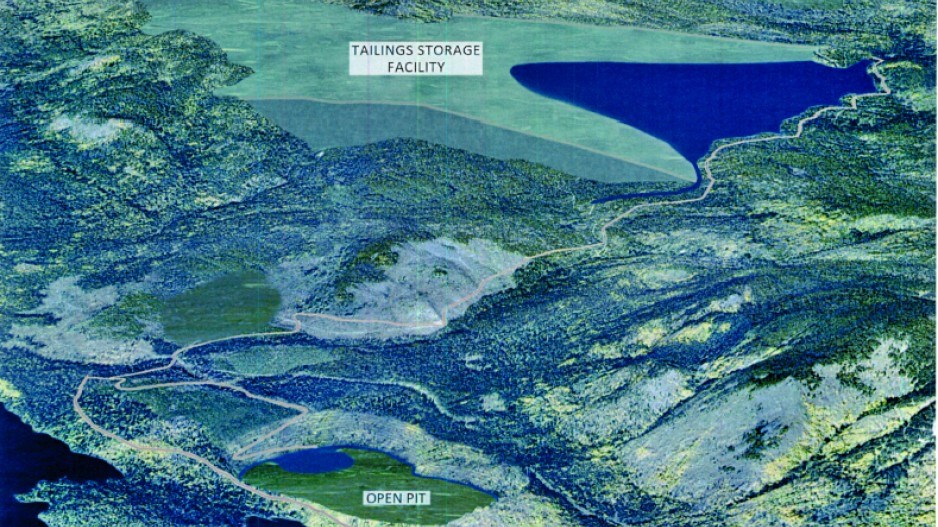

The Morrison Lake copper mine, 65 kilometres northeast of Smithers, was problematic because it would have been located next to Morrison Lake, which drains into Babine Lake, which is part of the Skeena River system.

Impacts on salmon habitat and the rights of the Lake Babine First Nations were important considerations. Even so, the company addressed all concerns raised in the EAO process.

The EAO’s executive director, Derek Sturko, wrote that “the proposed project does not have the potential for significant adverse effects and First Nations have been consulted and accommodated appropriately.”

But at the very end of the process, Sturko added a recommendation that “ministers consider a number of additional factors.”

Specifically, he recommended that the ministers “adopt a risk/benefit approach” and concluded by recommending against issuing an environmental certificate.

As the company’s lawyer pointed out, the executive director seemed to add a new test at the last minute – one that had not been used in previous environmental reviews.

After the court sent the Morrison Lake project back for reconsideration, the ministries of Environment and Energy and Mines ruled that Pacific Booker would have to go through a supplemental application if it wanted an EAO certificate.

Plourde said that was tantamount to saying, “Go and start over again” – something the company couldn’t afford to do.

Robin Junger, an aboriginal law expert with McMillan LLP and a former head of the EAO, said changing the rules in mid-process, as the provincial government appears to have done with both Pacific Booker and Compliance Energy, sends a bad message to the exploration and development sector.

“If people start thinking that these decisions are made based on how controversial they are, as opposed to the science of it all, it causes investors to lose confidence in the province, there’s no doubt about it,” he said.

“The question that this and other cases raise for proponents generally is: what is the basis upon which these decisions are made? Are we basing our assessments on science or Facebook likes?”