Cruise line operators are concerned that the Port of Vancouver’s (PoV) 2014 decision to close Ballantyne Pier to cruise ships has left them with less room to increase traffic.

The move surprised cruise-sector executives, said Greg Wirtz, who is president of Cruise Lines International Association, North West & Canada, and speaks on behalf of cruise line members.

He called the port’s move to close Ballantyne Pier “a self-inflicted wound” because it reduces capacity and funnels all cruise passengers to a single terminal at Canada Place to offload luggage and clear customs.

Were the two cruise ship berths at Ballantyne Pier operational, Wirtz said the city would have more flexibility to accommodate the cruise ship industry and less congestion in its downtown core.

“It’s not just the cruise lines that are hurt,” he said.

“It’s the local industry stakeholders – the companies that supply cruise lines and provide services, such as taxi companies. Those companies are hurt by a reduction in capacity.”

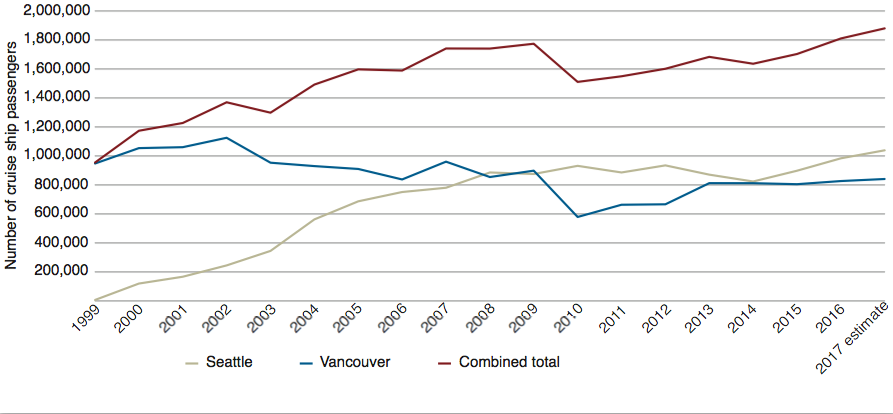

Vancouver’s cruise industry hit a high of 1,060,383 passengers in 2002, when Seattle welcomed 244,905. Seattle’s cruise passenger count has risen steadily since then, and the Washington state city this year is on pace to welcome more than one million cruise passengers for the first time.

Vancouver’s 2017 passenger count is projected to total 841,000.

Peter Xotta, the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority’s vice-president of planning and operations, defended the port’s decision to close Ballantyne Pier to cruise ships and said that the pier is now being used year-round to increase the port’s capacity for containers.

He noted that Ballantyne has always been a peripheral cruise ship terminal and that its two berths accommodated a combined nine cruise ship calls in 2014, while Canada Place’s three berths hosted 237.

(Chart source: Port of Vancouver, Port of Seattle)

A bigger concern for Wirtz, however, is whether the port has a plan to accommodate cruise lines once larger ships start replacing the current fleet.

PoV followed up its Ballantyne decision by sending infographics to cruise lines clarifying overhead-clearance buffers under the Lions Gate Bridge.

While Xotta stressed to Business in Vancouver that size restrictions for ships to pass under the bridge using a two-metre safety buffer have not changed, Wirtz said it is new information.

Adding to the lack of clarity for cruise lines is that the PoV was not able to provide BIV with the height of the tallest possible cruise ship that is able to pass under the Lions Gate Bridge’s centre span at low tide. The tallest ship at high tide could be a maximum of 57.4 meters.

“At some point, cruise lines are going to want to upgrade the ships that they’ve got in Vancouver to bigger ships,” Wirtz said.

“Chances are those ships will be too big to get into Vancouver.”

Royal Caribbean International (NYSE:RCL) already operates an Alaskan cruise ship that is too large to get under the Lions Gate Bridge.

While its 16-year-old, 2,100-passenger Radiance of the Seas sails out of Canada Place, its 17-year-old, 3,250-passenger Explorer of the Seas operates out of Seattle because it is too large for Vancouver’s infrastructure.

Royal Caribbean’s largest ship – the year-old, 5,450-passenger Harmony of the Seas – operates in the Caribbean. The cruise line has an even larger, 5,497-passenger ship on order for delivery next year.

Xotta acknowledged that cruise lines are buying larger ships and that, in the future, it is possible that a smaller percentage of cruise lines’ ships will be able to sail under the Lions Gate Bridge.

(Image: The Port of Vancouver in 2017 is set to receive calls from 33 ships that are part of 15 different cruise lines | Port of Vancouver)

“We’ve initiated work, call it a pre-feasibility assessment, of alternative locations for cruise ship terminals,” he said.

The port has hired a consultant to produce a report outlining options if the allowable clearance under the Lions Gate Bridge starts to significantly hurt Vancouver’s cruise ship business.

Xotta declined to name the consultant.

Options include raising the bridge and building a new cruise ship terminal elsewhere in Metro Vancouver. Both choices would be expensive.

Richmond Mayor Malcolm Brodie and Delta Mayor Lois Jackson told BIV that it is too early to speculate about whether their communities would be chosen as a site for a future terminal, yet neither was opposed to the idea.

Meanwhile, Toran Savjord, senior project manager of Newport Beach, a planned 100-acre waterfront development project in Squamish, believes that Squamish would make a great place for a cruise ship terminal even though it is more than an hour’s drive from Vancouver.

“We’re 40 minutes away from Whistler,” he said.

“We have a world-renowned gondola. Squamish was named one of the top [52] places to see in the New York Times and voted one of the most beautiful fiords in North America.”

However, Wirtz agreed with tourism advocates, such as Tourism Vancouver CEO Ty Speer, that tourists want to visit downtown Vancouver and not a terminal elsewhere in the region.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that it is a better experience to land and be able to immediately enjoy an amazing city,” said Speer.

“You don’t get that if you look at other options, like Tsawwassen. No offence but that’s nothing but a terminal facility.”•