A Vancouver company is hoping to disrupt the local construction framing industry with new technology that can “print” steel studs and accelerate the building process.

LifeTec Construction Group Inc., which has an 8,000-square-foot warehouse near East Broadway and Renfrew Street, has already caught the attention of some local upscale homebuilders and has taken on a number of small, private projects. The company said the plan is to move eventually into construction of mid-rise and commercial/industrial structures traditionally built from wood.

LifeTec founder and president Krishna Jolliffe said 3D-printed steel’s advantages over wood include durability, resistance to mould and warping, environmental friendliness and shorter construction time.

“Right now, on any construction project in the Lower Mainland, time is a huge factor,” Jolliffe said, citing Lower Mainland’s construction labour shortage and its impact on building timelines and costs. “When you are dealing with a lack of labour, speeding up those time frames creates huge efficiencies for any builder. So I don’t think we’ll always be able to show people savings, because we aim to come in at the same cost as traditional methods, but on any project, we’ll have a significant time advantage.”

LifeTec uses the Framecad system, which was first introduced in New Zealand but is now available throughout Australia, Asia, Europe, Africa and South America.

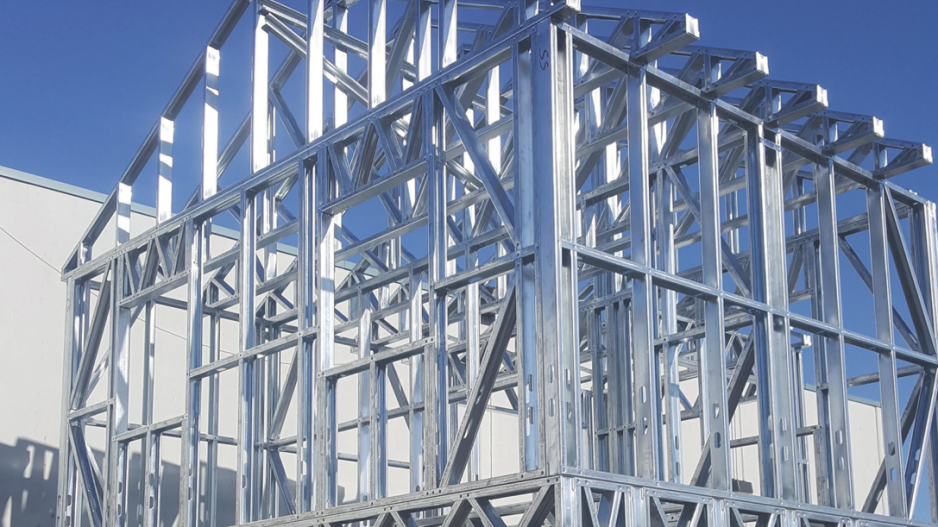

Typically, 3D printing for metallic materials like steel uses lasers to shape the steel source material, and the printers can reach extremely high temperatures during operation. But Jolliffe noted that LifeTec's process is completely mechanical - with a building’s frame designed on a computer, then having individual modular parts, studs and panels manufactured by specialized 3D printers. The parts are then shipped to the construction site and assembled, with minimal on-site cutting, drilling or modifications.

"There is no heat created whatsoever (in LifeTec's process), which is a big part of our manufacturing value proposition," he said. "Any manufacturing process that creates high heat means a lot of energy is required; whereas our process consumes minimal amounts of energy."

Tthe overall space requirement for a single 3D printing machine is much smaller than what is needed for production-line steelmaking equipment.

“If we can work with the developer early enough, we can show up right when the foundation is complete, and it’s three to five days from there to assemble the house – as opposed to three to five weeks for building it from wood,” said LifeTec COO Jesse Goldman, pointing to a two-

storey demonstration structure in the company’s warehouse that took under two days from conception to completion.

“Steel is just a way better product. If you look down the list … there’s just no doubt about what’s better in every category in terms of being a construction material.”

Jolliffe and LifeTec co-founder Mckinley Hlady, originally from Salt Spring Island, have been involved in the construction industry for years but first came into contact with 3D-printed steel as recently as 2016, when working on a sustainable housing project in South Florida. There, Jolliffe said, all of the project’s specified framing was done through printed steel.

That’s when the two B.C. men decided to bring the concept to their home province despite the dominance of wood as a structural building material in the local construction industry.

LifeTec started earlier this year with a team of 10, and the builders who were introduced to the building method were all receptive to the innovation, the company said.

And although the five current projects LifeTec is working on are all private detached homes, Jolliffe said they want to move into multi-family residential and mid-rise commercial/industrial because it’s in these larger construction projects, which have a need for a higher level of uniformity across a bigger scale, that printed steel’s efficiencies really shine.

“The sky’s the limit,” Jolliffe said. “We can do anything that can be done with wood. The only construction we can’t do is for highrises, but we can still do all the infill framing. We can do that at the same cost of existing providers, but at three to four times the speed. So we can create efficiencies in practically every construction process going on in the market.”

LifeTec representatives said they’ve already had conversations with local public organizations, including an unspecified local school board, about potentially taking on larger projects, and Jolliffe noted that the company is quickly outgrowing its current space, which is enough to house just one 3D printer for manufacturing the steel modular parts. He said he’s hopeful that the company will have a full manufacturing facility featuring three or four machines, in addition to an office, within two years.

“People sometimes confuse us with steel-stud construction, which is like wood in that you cut all the pieces of the frames on site, and cutting steel takes longer than cutting wood, logically speaking,” Jolliffe said. “People worry about the cost associated with that.

“But with Framecad, everything’s printed beforehand, and the end cost to the consumer is usually the same as wood construction.”

Goldman said that the education process will take time, but added he is optimistic that, given Metro Vancouver’s acute need for housing and its focus on environmental friendliness, LifeTec can offer the market a long-awaited solution.

“The end goal is that I don’t want to see anything built out of wood anymore,” Goldman said. “This system of building in every other part of the world is huge. It’s just here, in this little pocket in the Pacific Northwest where you have so much access to lumber, that it’s not as big. But it doesn’t mean [Framecad steel] isn’t a better system; it’s just that people haven’t been give a reason to switch up to this point.” •