B.C. Premier John Horgan says his government never meant to provoke a fight with Alberta when it announced proposed restrictions aimed at halting the $7.4 billion Trans Mountain pipeline expansion.

But he’s got one now, and it’s a fight that he might have to wage on two fronts, because this time around, a Trudeau government might be on Alberta’s side, at least in words if not in action.

“We started it,” said Iain Black, CEO of the Greater Vancouver Board of Trade. “We unnecessarily kicked the hornet’s nest on this one on a project that has been thoroughly studied.”

On the B.C.-Alberta front, $16 billion worth of Alberta-bound goods and services from B.C. could be vulnerable to boycotts and trade sanctions.

On the B.C.-Ottawa front, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has already said the $1.5 billion Oceans Protection Plan is off the table if the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion is halted.

There are billions more in federal funding for infrastructure projects that could be used as a political football, if relations between Ottawa and B.C. sour the way they did under Glen Clark’s NDP government in the 1990s.

B.C. had hoped to tap federal green infrastructure funds, for example, to beef up transmission lines between B.C. and Alberta so that B.C. could sell electricity to Alberta.

That already now appears to be dead in the water, because one day after B.C. announced plans to restrict increased flows of diluted bitumen from Alberta, Alberta Premier Rachel Notley cancelled talks between B.C. and Alberta on electricity sales.

One week later, she announced that $70 million in annual sales of B.C. wines into Alberta would be banned and hinted B.C. craft beer could be next.

Horgan last week made it clear his government does not plan to respond with tit-for-tat sanctions against Alberta beef. But he also said he isn’t backing down from his intention to subject the Trans Mountain pipeline to yet another review as well as restrictions.

“I will be resolute in protecting the interests of this great province,” he said. “Nor will I be distracted by the events that are taking place in other jurisdictions.”

In 2013, B.C. exported an estimated $16.6 billion worth of goods and services to Alberta. Of that, $7.2 billion was in the form of goods; the rest was in things like professional services.

The value of the goods exported to Alberta exceeded B.C. exports to China in 2013 ($6.6 billion), according to the Business Council of BC.

Ironically, one of the most valuable B.C. exports to Alberta appears to be the condensate that is used to create the diluted bitumen that Horgan wants to restrict.

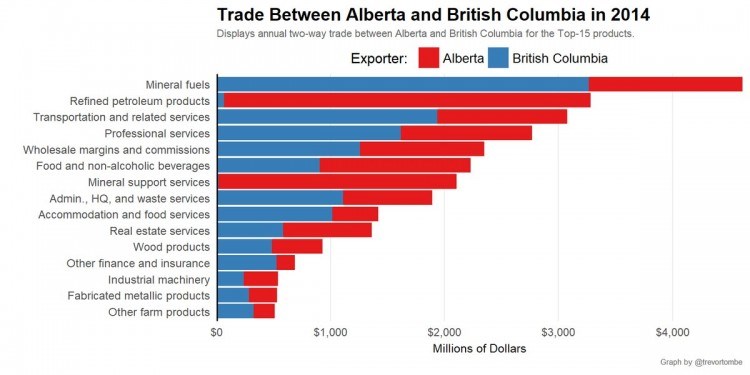

According to a chart created by Trevor Tombe, associate professor at the University of Calgary’s economics department, the most valuable B.C. export to Alberta is $3 billion worth of “mineral fuels,” which would include natural gas and gas liquids, like condensate.

Alberta United Conservative Party Leader Jason Kenney has suggested slapping a toll on those imports. That would hurt the industry Kenney wants to protect, because most of the producers operating on the B.C. side of the Montney formation are Alberta oil and gas companies.

“There’s no win here,” Tombe said. “Trade wars involve shooting yourself in the foot.”

Black isn’t too concerned that Ottawa might use the $2.2 billion in federal funding for public transit in the Lower Mainland as leverage against B.C. But he is worried that B.C. ports and the Asia-Pacific Gateway strategy could be vulnerable both to trade sanctions from Alberta and to restrained federal infrastructure spending.

“We are very focused on transportation-based infrastructure for the port, rails, airports, the road system,” Black said. “This is a very crucial element of our economy, and we cannot see it continue to grow the way that it has in the last 10 years without additional, very meaningful investment from the federal government. So anything that a provincial government does to sour the view of British Columbia through the lens of Ottawa is not very helpful.”

If Alberta decides to play hardball, he said it could target B.C.’s ports.

“They could say any railcar passing through the province of Alberta on the way to British Columbia is now going to pay a fee. And suddenly all of the shippers will start diverting thousands of trains a year south of the border.”

Interprovincial trade between the four western provinces is guided by the New West Partnership Trade Agreement. Each province holds a monopoly on beer and wine, so they are an easy target for boycotts and trade sanctions.

But there are also labour mobility and certification agreements that have removed provincial barriers to allow for a freer flow of labour. Provinces can tinker with those agreements.

“There are hundreds of regulatory elements that have been solved that Alberta – or British Columbia – could very quickly just change and frustrate the private sector trying to do business with each other,” Black said.

Tombe said B.C. does not have a legal leg to stand on, in its authority to restrict oil from Alberta.

Even so, there is a danger that the endless hurdles B.C. is trying to put in the project’s way could succeed.

“If you delay these investment projects too long, this does have real implications for the proponent,” Tombe said. “If you delay it too long, they may pull out.”

And that might be the single biggest negative economic impact from the dispute between B.C. and Alberta: damage to investor confidence.

“We’ve got a premier who flew back from Asia to try to convince the Asian communities that a final investment decision is warranted on B.C. LNG [liquefied natural gas],” Black said.

“How could they possibly see fit to make a final investment decision of billions of dollars over three or four decades into British Columbia when we can’t get along with our neighbours over a project that has already been studied and approved by the national government?”

Val Litwin, president of the BC Chamber of Commerce, said Ottawa needs to make it clear to B.C. that it has no constitutional authority to restrict what moves on a federally mandated pipeline.

“This issue now sits, I think, squarely on the shoulders of Justin Trudeau,” he said. “And we need to move beyond sound bites at town halls. There needs to be some sort of statement that no more challenges will be considered.”