Henry Wakabayashi recounts being at a BC Ferries board meeting listening to Manuel Achadinha give a presentation. As Achadinha went on at length to an impatient room, speaking passionately about his latest idea, then-BC Ferries chair David Emerson jumped in, saying, “If you stop talking, we’ll approve it.”

This might just be urban myth, but even Achadinha acknowledges his penchant for digging his heels in to get what he wants.

Born and raised in Victoria, the head of BC Transit says he inherited his work ethic from his parents, Portugese immigrants. He considers his father, a stone mason, one of his biggest mentors, and worked for him for a while when he was younger.

But a career in brickwork was not part of Achadinha’s future. After he graduated with a bachelor of economics from the University of Victoria, he pursued a master’s degree in public administration and landed in a co-op program with the federal government in Ottawa, where he cut his teeth learning about Crown corporations.

“It was really fascinating watching a Crown corporation operate in a dual sphere of government and business,” Achadinha said. “A lot of the people I dealt with in Crown corporations were committed to being efficient and effective and had the passion to run a good business. That really influenced and supported my thinking.”

After this initiation, he continued his government work back in B.C. in the Ministry of Finance for the Treasury Board staff.

“If you want to see how government is working, work in the department of finance,” said Achadinha, who spent 10 years in the ministry.

When the BC Liberal government came into power in 2001, BC Ferries came under the microscope and new CEO Doug Allen handpicked a group to help him transform the Crown corporation into the administrative hybrid BC Ferries Authority. Among its members were Achadinha and Wakabayashi, who owned a project management company. The two worked closely together during the BC Ferries transition and then again when Achadinha was headhunted by BC Transit in 2008.

Leaving BC Ferries to become president and CEO at BC Transit was one of the toughest decisions he had to make, said Achadinha, who found the cultures quite different.

“I came from a very focused business approach on how to do things,” he said. “I was used to the crazy pace at BC Ferries. It seemed very slow to me that first day. Maybe I was in shock mode.”

Within a year, however, Achadinha was knee-deep in BC Transit operations with a rewrite of the organization’s strategic plan for 2030.

“The ability to come into an organization and write the strategic plan or shape it was really important to me,” Achadinha said. “And really setting the direction of where the organization is going; I think anyone coming in wants the opportunity to set that direction.”

That strategic plan has informed numerous new projects – and stirred some controversy, especially when it comes to bringing the public on board.

“The biggest challenge for any transit organization is the perception of transit historically,” he said. “In North America, apparently it’s our God-given right to drive our cars everywhere and anywhere we want.”

For Achadinha, solutions start at the level of urban planning, in the development and integration of thoughtful transit plans.

“The challenge is how to provide a sense of independence and the opportunity to move around and make it convenient for them,” he said. “We have to stop asking why we invest in mobility but how we invest in mobility. We need to make communities more mobile – how we move people and how we move goods – and transit is a key component in that.”

Besides stickhandling the strategic plan, Achadinha found out (after he was hired) that he was going to be on the transportation committee for the 2010 Winter Olympics. As part of BC Transit’s contribution to the “green games,” Achadinha had less than two years to put together a hydrogen-fuel-cell fleet, complete with new garage and trained mechanics and operators.

Wakabayashi remembers the day he got the call: “He phones me and says, ‘Henry, you have to come and help.’ We had 18 months and he still had to buy the land, get the permits, deal with the City of Whistler for financing … but he had the facility up and running by the time Olympics needed it. I don’t know anyone else who could have done it.”

As with many Crown corporations, questions about BC Transit efficiencies eventually led to an assessment. In 2012, transportation and infrastructure minister Blair Lekstrom called for an independent review of BC Transit in response to concerns voiced by some mayors and other civic authorities about its performance and operations. BC Transit was put under the microscope looking for inefficiencies in its governance, funding and communication with regional partners.

Achadinha calls the review “fair.”

“Transit was transforming so much, and it was an interesting time because we were doing a major fleet replacement,” he said. “Local governments were getting concerned because costs were going up.”

“If you’re not being efficient and effective, government will come down on you, and I think they have every right to. If you can show people that you can run your company effectively and efficiently, and convince taxpayers that you’re investing their money wisely, people will support you. People don’t want to waste their money, and I don’t want to waste their money either.”

One of the things Achadinha is most proud of is the innovation that goes into the development and testing of new systems and new products.

“BC Transit has a history of lots of firsts – hybrid buses, low floor, first double-deckers,” said Achadinha. “Other transit organizations in North America come to BC Transit with new products asking us to test it out, or manufacturers come here because they know we’re willing to give it a try, and then transit agencies call us to get our feedback.”

As BC Transit directly manages Victoria’s transit system (the only one in the province not operated as a partnership model), the city can often serve as a test case.

“If you can do it here in Victoria, you know you can do it everywhere else,” said Achadinha. “We have all the information we can share with our regional operators. It’s like an incubator.”

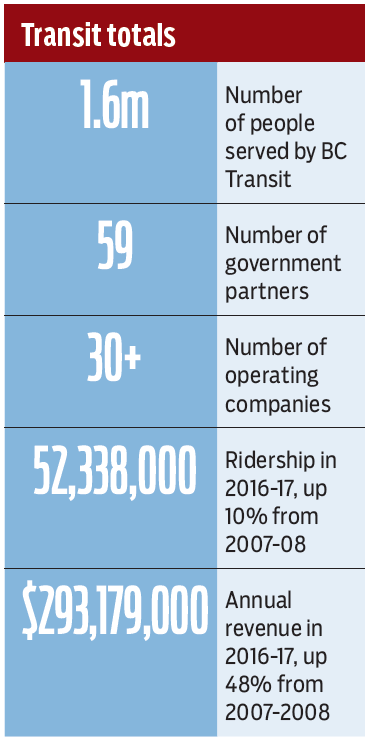

When Achadinha is not busy building fleets, driving buses or managing 52 million riders and $293 million in revenue per year, he enjoys hanging out with his wife and three boys in Mexico. •

Inside information: Manuel Achadinha

Currently reading (to his nine-year-old): Timmy Failure, Now Look What You’ve Done by Stephan Pastis

First album bought: Face to Face by the Angels

When you were a kid, what you wanted to be when you grew up: Professional soccer player or other athlete

Profession you would most like to try: Physiotherapist

Toughest business or professional decision: Leaving BC Ferries to move to BC Transit

Advice you would give the younger you: Slow down. Every time I accomplish something I’m quickly on to the next thing. Slow down, relax and enjoy the moment and the ride

What’s left to do: Continue using technology to transform transit. Prepare BC Transit for new ways of thinking and transforming itself again