For entrepreneur Rachel Chase, her business journey was sparked back in her childhood by a friend who was embarrassed by the cumbersome machine he had to wear because of a breathing problem.

Chase, co-CEO of Zennea Technologies and a Simon Fraser University (SFU) Beedie School of Business graduate, recalls her friend having to wear a large continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine for sleep apnea. The devices can resemble something out of a science-fiction movie as they encompass a full face mask with a long tube that’s connected to a machine plugged into an electrical outlet. According to the B.C.-based company Independent Respiratory Services, a CPAP machine can cost a Canadian upwards of $2,700 and is not covered by the B.C. Medical Services Plan. (It can be covered by extended medical insurance plans if prescribed by a doctor.)

“He would be embarrassed to use his CPAP machine in front of his friend or girlfriend,” Chase said. “But if he didn’t wear it, he snored so loud that he kept everyone else in the house awake.”

In her final year of studies, Chase enrolled in SFU’s Tech-E program, which brings together business students and mechatronic system engineering students and has them select a problem to solve with their final degree project.

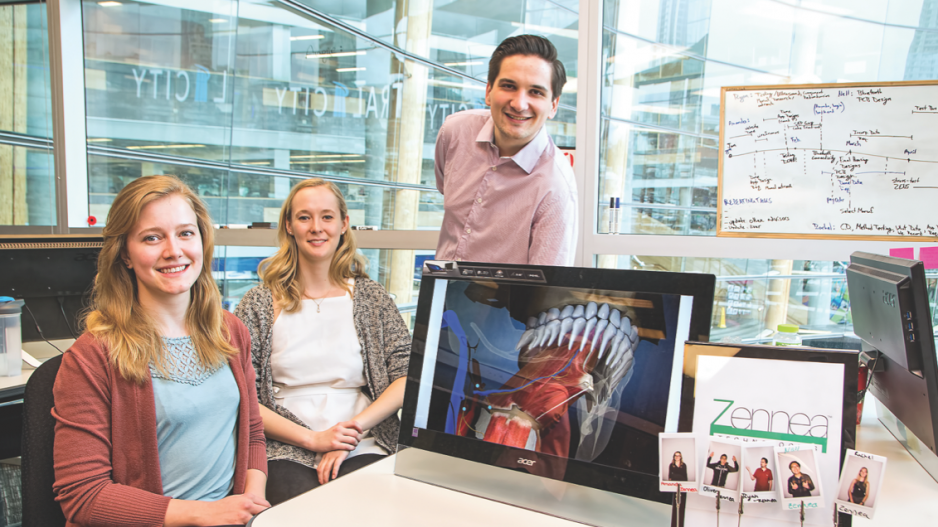

The team that would become incorporated as Zennea Technologies got together in November 2016. Chase, with mechatronics systems engineering student Ryan Threlfall and two others, set out to build a smaller, battery-powered, “sleep-wearable” CPAP prototype. The company is also working to have the device track sleep patterns of its users.

The project recently won Coast Capital Savings’ $35,000 Venture Prize competition and participated in China’s HAX program, the world’s largest hardware accelerator, based in Shenzhen. The HAX Accelerator is a subsidiary of SOSV, a venture capital and investment management firm in Princeton, New Jersey, that oversees US$250 million and aids about 250 startups each year.

Threlfall, who serves as co-CEO of Zennea Technologies, explained that Zennea’s device attaches to the underside of the chin along the jaw and is much smaller than the average CPAP machine.

“We realized in our market research that millions of chronic snorers aren’t getting proper sleep because of restricted airways, not to mention annoying their partners at night,” he said. “But [they] were either undiagnosed with sleep apnea, or told that their chronic snoring wasn’t serious enough to be treated by a CPAP machine. This is when we pivoted our target market to those who are chronic snorers, rather than those who suffer from sleep apnea.”

According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, roughly 40% of adult men and 24% of adult women are habitual snorers.

Chase said that if Zennea were to try to manufacture a medical product in Canada, it might take upwards of seven years for it to hit the market. The company’s device will not have to go through that rigorous approval process, but still serves the growing market for health-related technology.

Threlfall said users of the device will be able to track their sleep patterns and take that information to their doctor for analysis.

An increased awareness around wellness and exercise is a major driver of wearable technology, he said.

“The biggest thing people are worried about with a sleep wearable is how comfortable it will be and whether or not they’re able to sleep well with it on. If this problem is solved, in our experience, people are ecstatic to be able to understand their bodies better.” •