Mineral exploration can involve a fair amount of science that helps geologists guess where precious metals might be buried.

But at the end of the day, it also involves poking a lot of holes in the ground, at great expense, hoping to hit a deposit of gold or zinc or copper.

Thanks to the work of scientists at the Triumf particle accelerator, mining companies now have a new high-tech tool available that can paint a 3D image of what’s underground so that they can do a whole lot less drilling.

CRM GeoTomography Technologies Inc., one of six startups spun out of B.C.’s Triumf Labs, is now in the commercialization stage for a new imaging technology that is like an X-ray machine for the Earth.

Just as X-rays can produce images that can identify tumours and broken bones in the human body, CRM’s technology uses muon detection to identify densities underground that might indicate concentrations of metals, like zinc and copper.

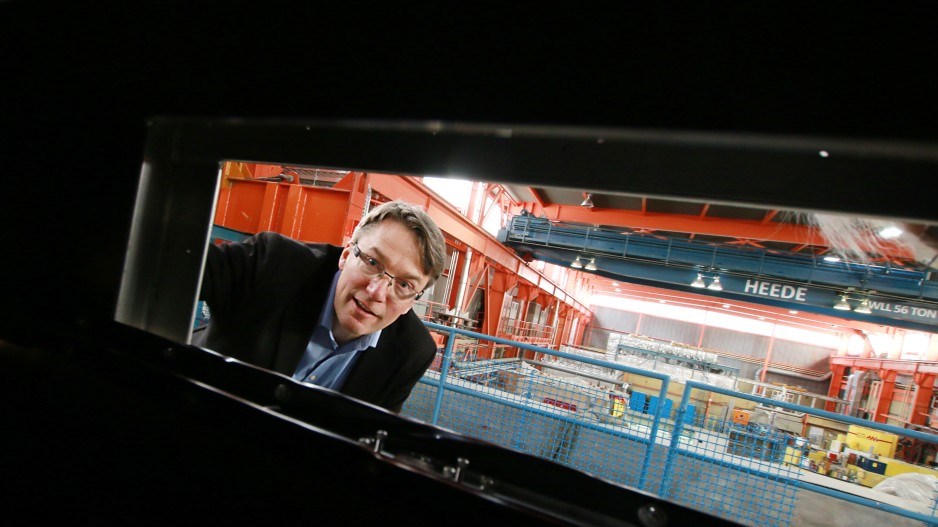

“Mineral exploration is getting more difficult because a lot of the easy stuff has been found,” said CRM CEO Don Furseth, whose background is in engineering physics and imaging and who has worked for Creo and MDA.

“There’s an abundance of different metals and minerals, but the problem is, of course, what you need for something to be economic is a nice high-grade deposit, and those are kind of hidden. What we’re essentially trying to do is provide better targeting.”

CRM is also now working with Queen’s University to develop an imaging system that could be used to monitor the efficiency of steam-assisted gravity drainage used in the extraction of bitumen from Alberta’s oilsands. Muons are subatomic particles similar to electrons, but with more mass. The Earth is bombarded by them. They have a range of intensities, and when a muon detector is placed underground, it can measure muon intensities to help pinpoint where pockets of density occur.

Those density pockets typically will include metals, like zinc. When the detectors are placed underground at a mine, or adjacent to a mountainside, they can create a 3D image.

It can’t tell geologists if the density pockets contain zinc, which is valuable, or pyrite, which isn’t, but it can give them a better idea of where to drill so they can find out.

Mining and exploration companies spent $1 billion on exploration in Canada last year, and $8 billion worldwide, Furseth said. The single biggest expenditure is exploratory drilling for samples.

“Because it’s an imaging-type technology, we can basically see through hundreds of metres of rock and see density anomalies,” Furseth said. “You can imagine – rather than just drilling, hoping to hit something, if we can image an area, then we can say, ‘Here’s where the density anomaly is.’”

The current generation of muon detectors that CRM developed is of use only for brownfield operations, because they require an existing mine shaft so they can be placed underground, beneath a region where there might be deposits that miners have missed.

But now that the technology has been demonstrated to work, CRM is developing a second generation of smaller detectors that exploration companies will be able to place underground via boreholes for greenfield exploration.

“We’re going to be moving from these larger detectors to the more compact ones to borehole next year, and that is something that the mining majors feel can have an impact on their processes,” Furseth said. “So it’s a pivotal time for us.”

CRM is one of six companies that Triumf Innovations has launched. Both CRM and Frontier Sonde are resource-sector focused. Frontier Sonde uses neutron imaging for enhanced oil recovery.

The Triumf lab at the University of British Columbia operates the world’s largest cyclotron – a proton beam accelerator that has been used for research in nuclear physics and the creation of radioactive isotopes used in nuclear medicine.

Triumf Innovations was established to take some of the science done at the Triumf particle accelerator and turn it into applied sciences.

“We are here to be the business interface for Triumf,” said Kathryn Hayashi, CEO of Triumf Innovations. “So, anything to do with spinoff companies, licensing, dealing with private-sector investors. We are here really just to be a professional business-facing portal both into and out of Triumf.”

In its early stages, CRM got financial and academic assistance from Mitacs, the National Research Council’s Industrial Research Assistance Program, the Geological Survey of Canada and, of course, Triumf Innovations.

But it is now generating revenue from mining companies. CRM’s detectors have already been used by Nyrstar at its Myra Falls zinc-lead-copper mine on Vancouver Island, by Teck Resources (TSX:TECK.B) at its Pend Oreille zinc-lead mine in Washington state and at the Cameco (TSX:CCO) McArthur River uranium mine.

“We feel we have a big opportunity in front of us,” Furseth said. “And although this organic path has been working, and it’s keeping us focused on meeting customer needs, it’s not a path to rapid growth. And if we really want to address all these other [potential applications], we will be looking to get investment to help us fund that growth and accelerate that.”