British Columbians will have to vote in the fall on whether to keep the current electoral system of first-past-the-post (FPTP) or to move to one of three types of proportional representation.

To better understand the three proposed systems of proportional representation (PR) as presented in Attorney General David Eby’s May 30 report, Business in Vancouver spoke with University of British Columbia political science Prof. Richard Johnston about the different types of PR presented – and on his mixed feelings about the referendum.

“On one hand, the attorney general avoided the temptation of putting a vague question on the ballot,“ said Johnston, “but on the other, two of the three alternatives have never been tried anywhere.

“If your fundamental goal is having seats proportional to the division of votes, it doesn’t matter a whole lot [which system is chosen].”

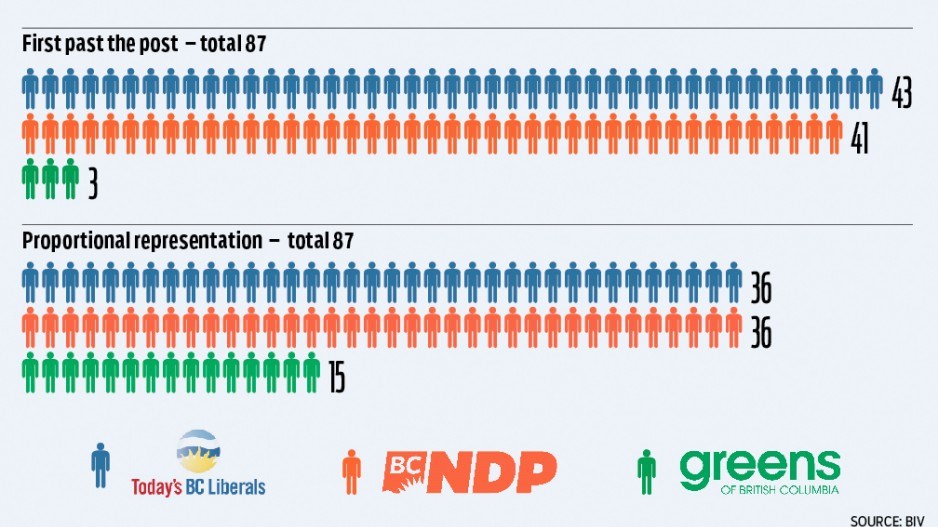

Under proportional representation, seats won by a party are relative to the popular vote. The results from last year’s general election, had they been based on the overall popular vote, would have given the BC Liberal and BC NDP parties close to 36 seats each, while the BC Green Party would have more than quadrupled their seat count.

However, Johnston warned that the effects of proportional representation can’t be projected so simply.

“Seats come first, and then we cast our votes,” he said. “How the seats are allocated is going to have a profound effect on how we vote.”

The electoral referendum report recommended a total number of seats between 87 and 95 for any system chosen and that parties be required to receive at least 5% of the provincewide vote to be allocated any seats – a deterrent against fringe parties.

Still, the systems vary widely, have no proposed maps for larger or combined ridings. Johnston said the government may have shot itself in the foot with their proposal.

“[They] underestimated the importance of being able to explain something,” said Johnston. “Whatever they were thinking, they were overthinking.”

Dual member proportional (DMP)

Two-member districts are created by combining existing districts. Parties nominate two candidates per district – one primary candidate and one secondary candidate – and voters cast a single vote for a pair of their choosing. Rural districts in this system would likely remain as single-member FPTP districts.

The first seat from a two-member riding will go to the primary candidate of the party that received the most votes, just as with FPTP. The second seat, however, is filled so that each party has the same percentage of overall seats as the number of votes it got across the province. Usually this is a different primary candidate, but a party could have both candidates elected if it did well in the riding and needs more seats across the province. As well, independent candidates would be elected if they place first or second in larger ridings.

Problems/questions

DMP is a new system and hasn’t been put into practice anywhere in the world. Although its results are proportional across the province, and all MLAs will represent their local districts, the second seat in each district might not be representative of the local vote. For example, a party with an overwhelming majority in a district might only get one seat, or the second seat may skip the runner-up and go to the third-place party if it is lacking seats across the province.

Mixed member proportional (MMP)

All electoral ridings increase in size by 50% to 100% but voting within them remains the same, with one candidate being elected by FPTP. Each region of the province then allocates additional seats from a party’s submitted list of candidates based on the provincewide results. The report submitted to cabinet recommended that at least 60% of elected seats be allocated from local single-member districts, with the remaining 40% to be filled by party lists.

Problems/questions

MMP is in use in a number of other countries, including Germany, New Zealand and Scotland, and Italy uses a similar system. Although it is the easiest to explain and understand, it favours regional over local representation, and the proposal as written leaves many questions left unanswered. Will people get one vote or two separate votes – one for a candidate and the other for a party? Will a party’s list of candidates be open to the public or closed? Can a candidate running for election in a riding also be on a party’s list in case they lose?

Rural urban PR

This system mixes two different types of voting, including the single-transferable vote (STV) system that was rejected in previous B.C. referendums. In rural areas, seats would be assigned by MMP as above, with single-member FPTP districts and extra candidates elected from party lists.

Under this system potentially giant ridings in urban areas would elect two to seven MLAs. Voters would rank candidates – as many as they want – in order of preference. Parties can nominate up to the number of MLAs to be elected in a riding, and ballots would display parties in groups, but the order of the candidates in the party and the order of the parties would be randomized.

Problems/questions

Rural-Urban PR is a unique system designed for Canadian use, but its components, STV and MMP, are used around the world. While the problems with MMP are reduced to rural ridings only, it brings back the debate over the STV system that British Columbians voted on twice previously. The system would be directly proportional, and the ranked ballot would allow voters to have the most direct impact, while also giving a potential leg up to independent candidates. However, the system is the most complex of the three choices, and relies heavily on how the larger electoral districts are drawn.