BIV special report: With the digital industrial revolution radically retooling the labour landscape, BIV looks at automation, unionization and other major issues facing employers, employees and the culture of work in the lead-up to Labour Day

A pivotal moment in Harry Bains’ life arrived one day in the 1970s, when he entered the lunchroom at his workplace, the former Eburne Sawmill, in south Vancouver, and found graffiti scribbled on a wall: “Hindu curry stinks. Hindus stay out. White man’s lunchroom.”

The mill employed about 650 workers, and more than 90% of them were Caucasian, said Bains, who grew up in a Sikh family in India’s Punjab region before emigrating to Canada at age 19 in 1971. He has since worked his way up to become B.C.’s minister of labour.

Bains and fellow Indo-Canadian workers at the mill sought and received support from their union, which together with employer Canfor Corp. (TSX:CFP) sent a strong message to all workers that racism would not be tolerated.

The experience prompted Bains to get involved in the union movement.

“I wouldn’t be in this position today if it wasn’t for the labour movement,” he said. “It taught me how to be an activist, not only for my own rights but as an activist on the part of other workers.”

Bains’ role in the B.C. government is largely to enact regulations to protect non-union workers in the province, although he also oversees the B.C. Labour Relations Code, which governs the framework for how unions can negotiate contracts.

He knows those negotiations well because that 1970s incident paved the way for Bains to spend 15 years as an elected officer at Steelworkers-IWA Canada Local 2171, and in union positions where he negotiated collective agreements.

The trend for other workers in B.C., however, has been to forgo unions and take private-sector jobs.

“Workers are voting with their feet and they’re saying that unions are not relevant any longer,” said Independent Contractors and Businesses Association spokesman Jordan Bateman.

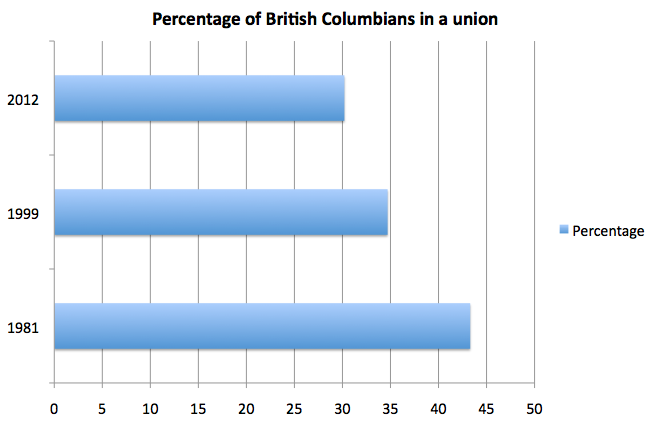

About 43.3% of B.C.’s workforce was unionized in 1981, according to Statistics Canada. That percentage fell to 34.7% in 1999 and to 30.2% in 2012. Union membership rose, but not as fast as the general workforce.

Source: Statistics Canada

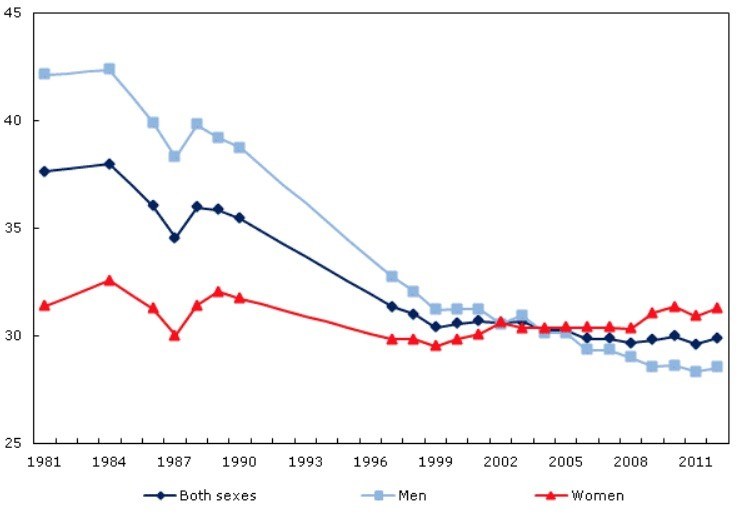

A closer look at trends in union membership Canada-wide reveals another trend: an increase in female members and a decline in the proportion of men.

Unionized men represented 42.1% of the male workforce in 1981, yet only about 28.5% of the male workforce in 2012. Unionized women, in contrast, represented 31.4% of the female workforce in 1981 and were at almost that same level, 31.3%, 31 years later.

The explanation for that disparity is that male-dominated unions in the private sector, such as those for loggers or longshoremen, have become far less prevalent while female-dominated unions in the public sector, in fields such as health care and education, have become larger.

Regardless of the demographics within unions, Bateman believes that the decline highlights shrinking union importance.

“If a company mistreated its workers today, thanks to social media and the way news is distributed now, they would never get away with it,” he said. “They would never get away with the things that happened 75 or 100 years ago.”

Unionization in Canada

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, 1997 to 2012; Labour Market Activity Survey, 1986 to 1990; Survey of Union Membership, 1984; Survey of Work History, 1981

A brief history of union evolution in B.C.

The labour movement has been active in the province since before 1858, when B.C. became a British colony. A collection of miners from Scotland made a long sea voyage to B.C. in 1850 to work in a coal mine but immediately went on strike when they learned that they first had to dig the mine, according to Rod Mickleburgh, who wrote the 2018 book On the Line: A History of the British Columbia Labour Movement.

The first union that Mickleburgh could find mentioned in B.C. historical records was the Bakers’ Society in 1859, he said.

Among the chief goals of early B.C. unions were a defined workday of eight or nine hours, a safe workplace and restrictions on Chinese labour.

“They were very, very anti--Chinese, except for a few enlightened labour leaders,” Mickleburgh told Business in Vancouver. He said early Caucasian unionists did not like Chinese workers because they accepted lower wages and were brought in as strikebreakers.

“[Unions] kept petitioning Ottawa for the head tax and a ban on any immigration of Chinese workers,” he said.

Mine catastrophes killed scores of workers – the worst one being the 1887 Vancouver Coal Mining and Land Co. disaster near Nanaimo, which killed 150 men. That disaster underscored the precarious nature of mine work as well as racism within the union, given that Chinese workers were blamed without proof that they had caused the incident.

A century later, the original tenets that unions fought for – a fixed workday and safe workplace conditions – had largely been achieved, while an appreciation of diversity and an intolerance for racism had been infused into the labour movement.

When the Social Credit (Socred) government in 1983 attempted to curtail union power, the labour movement joined with human rights and socially progressive groups to show some of the biggest displays of public support in the province’s history.

About 60,000 people paraded through the streets of the city on October 15, 1983, while the Socreds were holding a convention inside the Hotel Vancouver, Mickleburgh said.

This came a bit more than two months after 40,000 people packed a rally at Empire Stadium, and less than three months after a 25,000-person crowd protested in Victoria at the legislature, he said.

The movement, dubbed Operation Solidarity, aimed to abolish a government bill that kept workplace conditions off the bargaining table by restricting the scope of union negotiating to wages and benefits. The movement also took aim at a proposed law that would enable government to fire workers at will.

Many supporters were part of the broader Solidarity Coalition, which pressed the Socred government to re-establish B.C.’s recently axed human rights branch and a government branch that protected tenants’ rights, among other goals.

As part of a pact between former International Woodworkers of America (IWA) local head Jack Munro and premier Bill Bennett that ended the dispute, the government withdrew the bills, or parts of bills, that affected unions, but it went ahead with dozens of other pieces of legislation that provoked anger and disappointment among demonstrators for human rights and tenants’ issues, Mickleburgh said.

“They were sold out,” he said. “There’s no question about that. The question is whether it was Jack Munro’s fault.”

Munro, he said, had been in close contact with other union leaders before he made the pact with Bennett.

“They all ran for cover afterwards, and Jack got blamed for everything.”

Where do we go from here?

Reactions were predictable when the BC NDP government announced in July that billions of dollars’ worth of future government projects, including the Pattullo Bridge replacement and a four-lane highway between Kamloops and Alberta, will be built using union labour exclusively.

Under the initiative, community benefits agreements (CBAs) also require contractors to preferentially hire local workers and those from under-represented groups, such as First Nations members, women and people with disabilities. A new Crown corporation will aim to enforce government’s goal of making 25% of jobs available to apprentices who need to complete on-the-job training.

Union heads praised the news for helping to build communities while investing in young workers and giving minority groups a fair shot at work – all while paying workers fairly.

Private-sector company representatives, in contrast, dismissed the initiative as unnecessary for the training of apprentices and expensive because of extra costs for union bureaucracy. The Independent Contractors and Businesses Association announced August 27 that it has also filed a petition in B.C. Supreme Court asking that the government's union-only hiring model be struck down.

To what degree the initiative will increase unionization, however, is unclear.

“It will increase unionization rates in some of those building trades because some of those bids were going to non-union firms,” said British Columbia Federation of Labour (BC Fed) president Irene Lanzinger.

“This is a much better process…. People get trained. Local people get hired. People earn decent wages so their kids aren’t living in poverty.”

The CBA initiative, however, is only one factor that will determine the strength of the union movement.

Bains told BIV that he is waiting for a panel to report back in the next few weeks with recommendations as to how his government can improve the labour climate in the province.

(Image: B.C. Minister of Labour Harry Bains expects to hear panel recommendations in a few weeks that will suggest ways to improve the labour climate in the province | Government of British Columbia)

Unions have urged the panel to recommend that the B.C. government change the province’s labour code provisions for how unions get certified.

The process requires union organizers to get 45% of workers in a workplace to sign union cards, and then to apply to certify a union. A 10-day campaign period follows, and then a secret-ballot vote is held.

Unions want the NDP to restore parts of the B.C. labour code that during the 1990s allowed union certification to go ahead if a simple majority of workers signed union cards, with no secret-ballot requirement.

Lanzinger praised the card sign-up system as fair because employers are now able to fire union organizers or mount anti-union campaigns to thwart unionization.

Bateman countered that B.C.’s Labour Relations Board helps maintain a fair campaign environment, much like Elections BC does in provincial elections, and that a secret-ballot vote is a fundamental democratic right.

Regardless of whether changes materialize on union certification, one thing is certain. The BC Fed will continue lobbying on behalf of workers who are not in unions as well as for workers who are in its dozens of member unions.

The organization has, for instance, maintained a call to raise the minimum wage to $15 per hour and has supported increased government coverage of the cost of prescription drugs. It also frequently weighs in on other issues such as the B.C. government’s position on ride sharing.

“We also see ourselves playing a role in terms of all workers in the province because people who belong to unions have a voice, and they have a union to speak for them,” Lanzinger said. “People who don’t have a union, they really have no one to speak for them except us.”

There are some issues in which the BC Fed stays on the sidelines.

It chose at its last convention not to bring to the floor a vote on whether to support megaprojects, such as the Kinder Morgan (TSX:KML) pipeline or the Site C dam, Mickleburgh said.

That reticence is because those issues reveal a schism in the membership between trade unions and environmentalists, he said.

“That debate has been there forever,” he said. “When Greenpeace was organizing to save Clayoquot Sound, the IWA was furious at the green movement and the protesters because they were costing the IWA good logging jobs.” •