New governments bring new tax regimes, and for businesses and residents in B.C., that adds up to increased tax burdens and complexities in 2019.

“We’ve gone through an unprecedented series of changes over the last three years in our tax system,” said Phil Ross, tax partner with accounting firm Grant Thornton LLP. “I think there’s probably an appetite for a pause so that we can come to grips with the changes.”

That appears to be the sentiment shared by some accountants adjusting to the changes resulting from the defeat of long-standing governments, but not everyone agrees that the modifications are unprecedented.

Kevin Milligan, professor of economics at the University of British Columbia, refers back to the federal Conservative government’s introduction of the goods and services tax (GST) in 1991 and changes in the 1970s that overhauled Canada’s tax code.

Recent tax code changes will also have a significant impact on paycheques, 2018 tax filings and 2019 municipal tax bills.

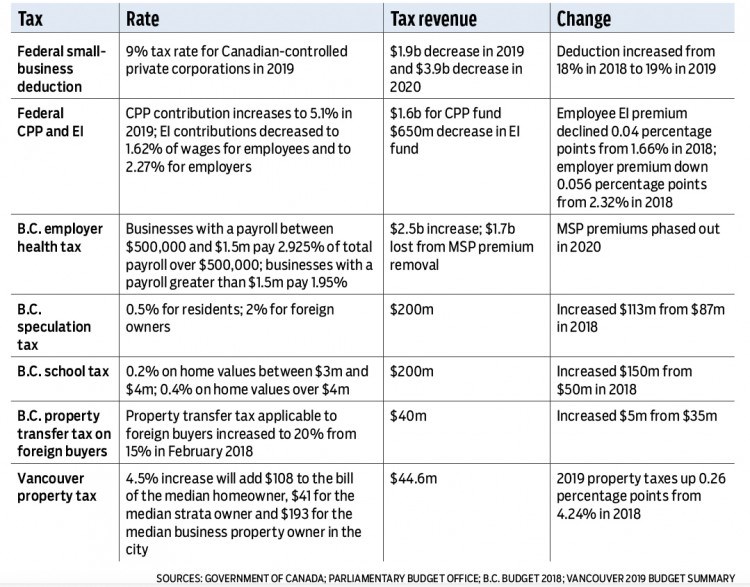

For example, Ottawa lowered Canada’s small-business tax rate and adjusted Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and employment insurance (EI) contribution rates.

CPP contributions and payments will increase over the next seven years to raise the amount retirees receive to 33% of their average work earnings from the previous 25% target.

In 2019, the CPP contribution rate will increase 0.15 percentage points to 5.1% from 4.95% of pensionable earnings, which means that in 2019 the average Canadian with a salary of $51,000 can expect to pay an additional $71.25 annually and his or her employer will match these contributions.

Higher employer and employee CPP contributions will be offset somewhat by EI premium contributions, which will drop by $0.04 per $100 of insurable earnings for employees and $0.056 per $100 for employers. However, CPP contribution increases could encourage some small-business owners to stop paying themselves as an employee and start paying themselves through dividends to avoid making CPP payments.

Canadian small businesses will benefit from a lower federal tax rate when filing their 2019 corporate tax returns later this year. The rate fell one percentage point to 9% of taxable income resulting in a combined federal and B.C. tax rate of 12%.

But Canadian-controlled private corporations (CCPCs) face new restrictions on income sprinkling. Previously an incorporated small business’ income could be split (sprinkled) among family members to reduce the family’s tax burden. But a CCPC must now compensate family members only for actual contributions to the business.

A higher tax rate on active income for CCPCs whose passive income exceeds $50,000 was also introduced in 2018.

Milligan said the changes will help to refocus the small-business tax rate on improving incentives to invest in mom-and-pop businesses.

But Ottawa and the Canada Revenue Agency aren’t the only ones instituting major tax changes. The almost two-year-old BC NDP government has also made numerous revisions to the province’s tax system.

One of its most contentious changes will be how the province funds its medical services as it eliminates Medical Services Plan (MSP) premiums charged to individuals and switches to an employer payroll tax.

The new employer health tax was implemented on January 1, 2019, but employee MSP premiums will not be phased out until January 1, 2020. Higher employer MSP costs will likely be passed on in some form to employees and consumers.

Milligan said that while the changes won’t have a long-term effect on employment, they could reduce employee bargaining leverage in future wage negotiations. He also pointed out that many big employers were already paying their employees’ MSP premiums so the change will have little impact on them.

Many B.C. municipalities have complained that the new health tax will increase their operating costs significantly because municipal operations are highly dependent on labour. As a result, many B.C. municipalities will likely raise municipal property taxes to fund the higher costs.

The City of Vancouver’s new council has already voted to increase 2019 property taxes 4.5%. The new employer health tax accounts for one-third (1.7%) of the increase. B.C. is the last province to eliminate the medical services premium model.

Milligan downplayed concerns that higher employer taxes will discourage companies from hiring new staff. He said Canada’s employment taxes are relatively low when compared with other G7 countries. According to Milligan, the tax that will have the most negative impact on the province’s business competitiveness is the provincial sales tax.

Economists typically support consumption, or value-added, taxes such as the GST and the harmonized sales tax (HST), because the end-user (consumer), not businesses, pays the tax.

But the polarizing debates that sank B.C.’s HST in 2011 have left the province with a lack of political will to institute another value-added option.

Ross said the more obvious route for the provincial government would be to address the PST’s impact on business competitiveness rather than raise personal income tax rates. •