After reporting a record number of B.C. real estate audit assessments in 2018 – amounting to roughly $170 million – the Canada Revenue Agency is expected to receive a treasure trove of data from the B.C. government tying home ownership to income declarations.

The province is estimating it will collect $642 million over the next four years from the newly implemented BC speculation and vacancy tax, aimed at satellite families and those who leave their secondary urban homes empty for most of the year.

Whether these 2019 budget estimates hold water will partly depend on what the government deems to now be the “most advanced auditing processes in the country,” thanks in part to a suite of new efforts to collect information on home ownership.

Complex audits are bound to follow the submission of speculation tax declaration forms, policy and tax experts suggest.

The annual 2% tax against a satellite family’s assessed home value is designed to bridge a policy gap that has led to tax avoidance attributable to trends in global migration and the internationalization of B.C. real estate.

In essence, satellite family breadwinners earn income abroad while having their families live in B.C. The household thus pays little income tax in Canada but utilizes social services, the bulk of which is paid for by such taxes.

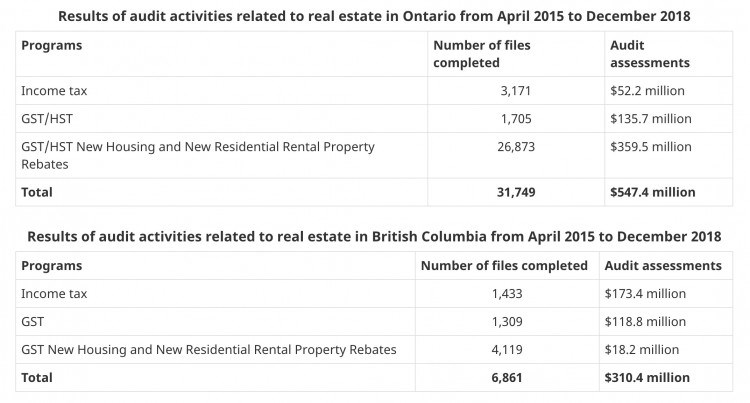

This chart shows the Canada Revenue Agency’s results of an augmented Ontario and B.C. real estate audit program commencing April, 2015. Ontario’s 31,749 audits averaged $17,241 in reclaimed taxes whereas B.C.’s 6,861 audits reclaimed, on average, $45,241.

B.C. real estate audits lucrative for the taxman

In 2015 the CRA augmented its compliance program for B.C. and Ontario real estate audits. Last month the agency issued a report claiming it had collected $140.7 million from 1,417 real estate audits in B.C. alone, from April, 2018, to December, 2018. That’s $99,294 per audit, well above the three-year average of $45,182 per B.C. audit, and miles ahead of Ontario’s average of $17,241 per audit.

Tax collectors are getting more efficient, it appears, as 1,470 B.C. real estate audits from April 2015 to March 2016 generated only $18.5 million in evaded taxes.

In B.C., $173.4 million of the $310.4 million recovered in taxes – from 6,861 audits since April 2015 – is income tax related (lifestyle audits of owners of expensive homes and capital gains assessments on home sales). The other portion relates to unreported GST on sales and house flipping. Ontario’s 31,749 real estate audits since April 2015 brought in $547.4 million. Overall, the CRA also applied $70.9 million in penalties for knowingly making false statements.

The $642 million estimated new tax revenue is payment of the speculation tax only. The B.C. government says it has not assessed the amount of tax from unreported worldwide income or capital gains could be recovered from the data it collects for the speculation tax. After Ministry of Finance experts declined an interview request from Glacier Media, the government said it does expect the speculation tax auditing process to help identify overseas tax evasion and thus the ministry is expected to flag audit leads for the CRA.

Out migration and expensive homes

B.C. technically defines a satellite family as one in which unreported worldwide household income is greater than local income.

Satellite family arrangements can be observed by looking at investor-class immigrant “out-migration.”

A government study of the now defunct federal investor immigrant program (foreigners paying an $800,000 loan for permanent residency), favoured by Chinese nationals, showed “out-migration” rates of investor immigrants after 10 years was 26.2 %, well above any other immigrant stream.

As an example, from 2006 to 2010, Canada admitted 13,151 investor immigrants and 34,544 of their spouses and dependents. According to the 2016 census, there remained only 7,590 of those investor immigrants and 27,370 spouses and dependents, showing a disproportionate number of breadwinners left the country within five years.

The average assessed value of homes owned by investor class immigrants in Metro Vancouver, in 2018, was $1.78 million for those admitted by the federal government and $2.2 million for those entering via Quebec, according to a recent Statistics Canada study. Furthermore, recent investor immigrants (since 2009) own single detached houses with average values of either $3.11 million for federal investors or $3.30 million for Quebec investors.

Of 121,650 investor immigrants admitted since 1986 and still declaring residency in Canada, 52% are now located in British Columbia, per census data.

Tax tries to close “bad tax setup”

Satellite family arrangement have given rise to wealthy people – often foreign nationals or recent immigrants – with access to foreign sources of money having a greater advantage in owning homes in Metro Vancouver than local income earners, said Josh Gordon, assistant professor at Simon Fraser University’s School of Public Policy.

Foreign money inflows into real estate by various means have decoupled housing prices from local income earners, Gordon contended, pointing to widely available data of the Vancouver real estate phenomenon where relatively low incomes are reported in some of the most expensive neighbourhoods in Canada.

Gordon said the purpose of the speculation tax is to close the gap on a “huge subsidy” due to a “bad tax setup.”

“It’s a tax avoidance problem, not purely tax evasion. This arrangement is perfectly legal and that’s the problem,” he argued.

“Over time much of the expensive property will come to be owned by people outside the labour market,” said Gordon.

Gordon said presumably higher consumption based taxes paid by satellite families are an inadequate substitute for any unreported or even reported worldwide income.

“Those families will be using the education and health care system for much of their life. The purchase of a couple luxury vehicles does not capture the services they will consume,” said Gordon.

Richmond’s Andersen Tax LLP international tax accountant Steven Flynn said at first glance the speculation tax should be able to capture those families whose breadwinner is not filing Canadian taxes. Should a satellite family try to file a speculation tax exemption, the federal and provincial governments should be able to cross reference low income to high property value, via the auditing system, said Flynn.

For satellite families, “in general terms, by filing for an exemption under the B.C. speculation and vacancy tax, you’re admitting to a government agency that you’re a Canadian resident for income tax purposes. The expectation is the individual is subject to Canadian income tax of their worldwide income,” said Flynn.

But some audits of overseas spouses could be tricky, said David Duff, professor and director of the LL.M. in Taxation program at University of British Columbia’s Peter A. Allard School of Law.

Duff said people make arrangements to ensure that they are not residents in Canada for tax purposes. So one could remain a non-resident for tax purposes in Canada even if their Canadian household does not pay the speculation tax.

“The key is that they’re not residents for Canadian tax purposes. Residence for tax purposes is not the same thing as citizenship or permanent residence status,” he explained.

Opaque, if not non-existent, spousal status; children (students) put on the title of homes; and income transferred by the non-resident spouse from offshore corporations make for a difficult gambit for Canadian auditors, should initial red flags, such as low income declarations from expensive homes, arise, Duff said.

“Perhaps the [speculation] tax will trigger real or fictitious separations for tax purposes,” he said.

And Flynn said under the federal tax act, overseas cash gifts do not count as worldwide income.

And so, to determine unreported worldwide income, said Duff, “since the CRA has no way to audit this income directly, it will have to rely on whatever information it is able to obtain from the jurisdiction in which the spouse is a resident.”

“It will be necessary to get information from other jurisdictions on the income of spouses of Canadian citizens or permanent residents who claim the exemption. This is increasingly possible with improvements in the international exchange of tax information, but a significant administrative challenge nonetheless,” Duff said.

Polling indicates the BC NDP’s new speculation tax is supported by four in five British Columbians, but the opposition BC Liberals and special interest groups have panned its implementation, citing objections such as allegedly unclear and unfair exemptions and privacy concerns about providing one’s social insurance number.

“I think its revealing that someone would be more concerned about connecting income tax data to property ownership than about widespread tax avoidance,” countered Gordon, who seems confident the tax will do what it is intended to do.

Flynn said collection of a SIN should not be a concern and would appear necessary to make the tax effective.

Bryan Short, director of the BC Freedom of Information and Privacy Association, said his group is “monitoring” the tax.

“If the B.C. government can demonstrate that the collection of SINs is absolutely necessary to the facilitation of the speculation tax, then they are not overstepping boundaries,” said Short, via email.