The country’s deficit is top of mind for many Canadians, particularly during an election year.

The majority of Canadians (58.3%) would prioritize balancing the budget over investing in government programs, according to a November Nanos Research poll.

But some economists are questioning whether concerns about government deficits are misplaced and whether public debt might be essential to a healthy private sector.

“By definition, whatever is spent is received by somebody else,” said Mario Seccareccia, a University of Ottawa professor of economics.

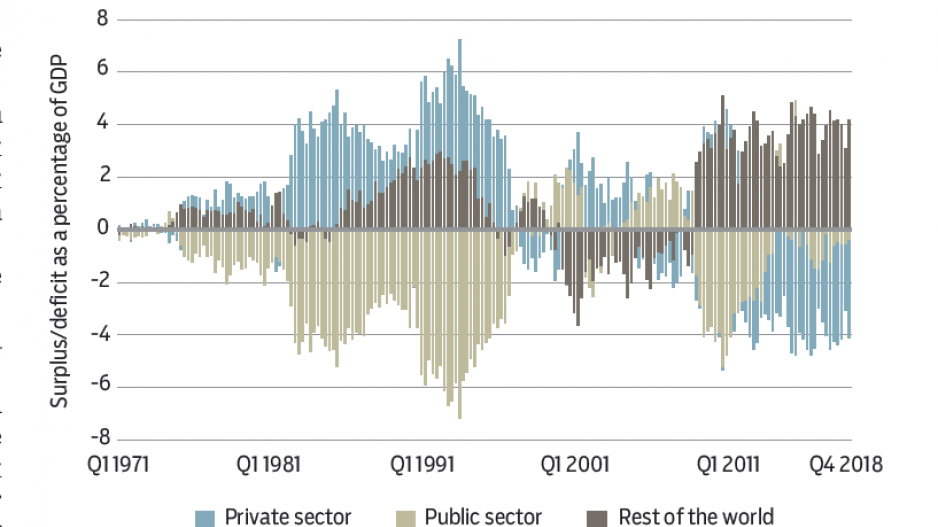

When the government spends tax dollars, they are received by Canada’s private sector or are sent out of the national economy to the rest of the world in the form of a trade deficit. Savings by Canada’s private sector and the rest of the world mirror government spending down to the dollar.

“Government budget deficits, like trade surpluses, generate savings,” Seccareccia said. “Therefore cutting the deficit destroys the saving capacity of the private sector.”

Running a federal deficit is the only way for the private sector to be in surplus if the country is running a trade deficit.

For both the Canadian private and public sectors to post surpluses, the country must take in more money from exports than it spends on imports. Over the past 60 years, Canada has achieved a sustained trade surplus only during the seven years preceding the 2007-08 global financial crisis.

The private sector needs to find money before it can spend it. Unlike the currency-issuing federal government, companies in the private sector with expenses that exceed revenue don’t operate for long. But while public spending isn’t constrained by revenue, the government cannot spend freely without consequence.

It must ensure the country has the resources it chooses to buy to avoid inflation and other negative economic consequences, said Brian Romanchuk, an economics researcher and blogger.

The issue isn’t finding money to buy goods, but rather having the capacity to support the purchase of those goods. The most prominent measure of capacity is unemployment. If the government ran deficits to create jobs and reduce unemployment, there would be little risk of inflation because it would be buying unused capacity in the economy. On the other hand, deficits used to buy limited resources could cause a shortage, overheat the economy and increase inflation.

How much a government should spend is a political, not an economic, decision, argue Seccareccia and Romanchuk. It’s not how much you’re spending, Romanchuk said, but rather what you’re spending it on and whom you are giving the money to.

Some economists are bucking the economic orthodoxy that has existed since the 1980s and arguing that some debt levels are too low. The U.S. has had six depressions in its history, and all of them followed periods of sustained surpluses, according to data collected by Randall Wray, professor of economics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Since the 1970s, each time the federal deficit fell below its average of 3.1% of gross domestic product (GDP), the U.S. entered into a recession, according to data collected in 2015 by Stephanie Kelton, chief economist on the U.S. Senate budget committee and professor of economics at Stony Brook University.

The same low public debt levels preceded the 2008 recession and the global financial crisis. Without a government deficit or trade surplus to support a private-sector surplus, corporations and households are forced to become net debtors.

Private debt could pose a bigger threat to the economy than federal deficits. Consumption driven by private-sector borrowing has been credited with helping Canada weather the global financial crisis better than most countries. However, it has driven Canadian private debt to 266.6% of GDP.

Private-sector deficits are largely the result of massive household debt wiping out corporate surpluses – with the exception of 2015, when oil prices collapsed.

The trade deficit should not be a problem in the short term, but Seccareccia said rising dependence on foreign products and servicing of capital is not good.

“The federal government ought to be concerned about this – especially in its promotion of free trade.” •