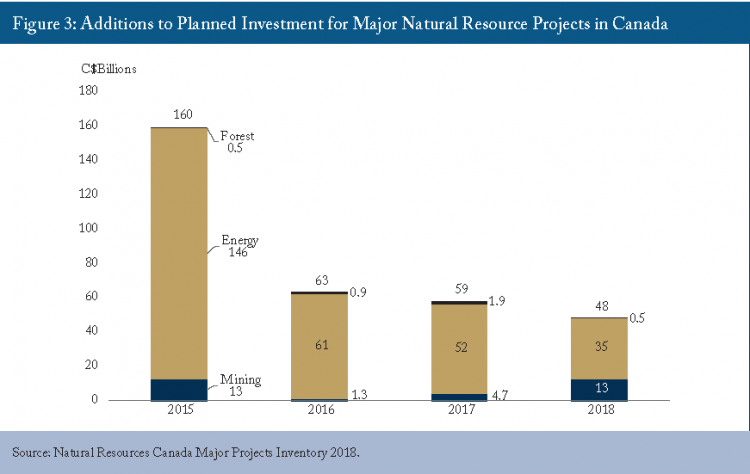

In just two years, under the Justin Trudeau government’s watch, $100 billion worth of energy projects were killed, cancelled or stalled, according to a new report by the C.D. Howe Institute.

That is equivalent to 4.5% of Canada’s gross domestic product.

During this time, investment in the Canadian oil and gas sector fell from $125 billion in 2014 to $75 billion in 2018. This was during a period when global investments in oil and gas increased, especially in the U.S., which had a 50% rise in oil and gas sector investment in 2017.

The trend was punctuated when Kinder Morgan Canada (TSX:KML), which had been prepared to invest $7.4 billion to expand the Trans Mountain pipeline, bailed, forcing the Trudeau government to buy the project for $4.5 billion.

Nor is it just the oil and gas sector that has suffered. Investment in Canada’s mining sector is disproportionately down compared with other jurisdictions, according to C.D. Howe.

While some of the biggest projects killed in Canada have been under the Trudeau government, there were problems getting projects approved and built under the Conservative government of Stephen Harper as well.

C.D. Howe blames Canada’s sclerotic regulatory regime for the killed and stalled projects and the flight of investment capital. And it warns that the fix proposed by the Trudeau government, Bill C-69, will make things worse, not better.

“We’re in a vulnerable spot,” said Grant Bishop, co-author of the C.D. Howe report A Crisis of Our Own Making: Prospects for Major Natural Resource Projects in Canada. “And it does seem that regulatory uncertainty is hindering Canada from attracting resource investment – a trend that’s confirmed by all accounts on the ground. The proponent of Energy East was pretty specific that they felt that regulatory uncertainty was a prime consideration when cancelling the project.”

Even the CEO of the one major energy project that has succeeded in moving forward – the $40 billion LNG Canada project – has expressed concern about Canada’s inability to get things done.

“As a relatively recent arrival to Canada, I am worried about this country’s future,” LNG Canada CEO Andy Calitz said in a speech in Prince George on January 22. “B.C. and Canada are resource rich, but at the moment, those resources are having a very difficult time getting to market.”

“In the United States, this would be characterized as a national security issue because it’s that significant to the economic future and direction,” said Jonathan Drance, a retired Stikeman Elliott partner who now works as an energy consultant.

Martha Hall Findlay, president of the Canada West Foundation, said, “In all of my involvement for decades now, I’ve never heard the phrase ‘sovereign risk’ associated with Canada, and that is now a regularly used term.”

The precipitous decline in investor confidence in Canada’s energy and mining sectors has been blamed in no small part on Canada’s environmental and regulatory review processes.

They take too long, are too adversarial and have become forums to debate issues that Drance said should have no place in what is supposed to be an analysis of environmental impacts.

The C.D. Howe report confirms that it takes longer for resource projects to move through the regulatory and environmental review processes in Canada than in Australia and the U.S.

But the cure that the Trudeau government has proposed may be worse than the disease, according to C.D. Howe and the Canada West Foundation.

Bill C-69 will overhaul Canada’s environmental and regulatory regime. Such an overhaul would be welcome if it improved things, but industry, economic think tanks and the government of Alberta warn it will make things worse.

“When I have CEOs of big companies say things like ‘We’re glad we’ve got our permits because under Bill C-69 we wouldn’t even bother applying,’ that is really damning,” Findlay said.

The bill would, among other things, remove regulators like the National Energy Board (NEB) and Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission from the environmental reviews of major projects like pipelines.

That would be a fatal mistake, says the Canada West Foundation. It agrees the NEB needs reform. But dismantling it and replacing it with a new regulator – the Canadian Energy Regulator – would result in the loss of considerable case law based on a number of court challenges of NEB and Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (CEAA) decisions.

As C.D. Howe points out, the courts have repeatedly upheld decisions made under the CEAA and NEB. Where projects like Northern Gateway and Trans Mountain foundered, legally, was on First Nations consultations, not the CEAA or NEB regulatory review processes.

One of the Bill C-69 concerns is a new test for deciding who qualifies to participate in hearings. Currently, only stakeholders that either are affected by the project or have relevant expertise typically get standing in hearings.

There is a fear that Bill C-69 will open up the review process to anyone with an opinion, regardless of whether they are affected by the project or have relevant expertise. And, Findlay said, Bill C-69 provides too much political discretion in making decisions before reviews are completed, or even begun.

“C-69 is loaded with political discretion,” Findlay said. “In an environment where we’re seeing a lack of trust anyway, this is hugely problematic.”

Drance said the problem with Canada’s regulatory regime now is that it is more like a court system, in which everything from the economics of the project to climate change and First Nations issues gets debated, when it should focus strictly on whether the project will harm the environment and how to mitigate that harm.

All of those other big-picture issues – First Nations reconciliation and climate change policies – need to be addressed at a high level by the federal government, not within the narrow confines of specific project reviews, he said.

Drance added that it is clear the current approach to project-by-project First Nations consultation isn’t working. He points to Australia, which made a concerted effort to settle rights and title issues with its Aboriginal people once and for all, as an example Canada should follow.

“We have had this process of open-ended, rather abstract consultation and accommodation of First Nations for roughly 20 years,” Drance said. “And it may be time to start settling some of these things.

“Australia has settled something like 300 or 400 of these kinds of disputes and has a register of title so that anybody developing a project knows exactly who to go to and what to negotiate. That may well have cut some years off the approval process in Australia.”

Tom Isaac, an Aboriginal law expert at Cassels Brock, said Canada could not replicate Australia’s omnibus approach to settling land issues.

Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution protects Indigenous and treaty rights – something that Australia doesn’t have.

“Australia can unilaterally impose whatever measures they want to impose when it come to title. Canada is the only nation-state on the planet that has materially fettered the power of the state to unilaterally run rough-shod over Aboriginal rights in our Constitution.”

See related stories, Pipelines continue to galvanize Canada’s political landscape and Anti-pipeline funds flow from unexpected sources.