Vancouver has seen the biggest increase in people choosing to walk, cycle or use transit to get around the city than it has in five previous years of tracking such data.

Together, the three modes of transportation accounted for 52.8 per cent of all trips recorded over one day of the week by 2,600 randomly selected participants in a survey last fall.

The increase in more trips made by walking, cycling and taking transit—up from 48.4 per cent the previous year—came despite 2,050 participants having access to a private vehicle.

“We’re seeing people drive less and less each year,” said Lon LaClaire, the city’s director of transportation, in an April 18 briefing at city hall. “It’s not that they’ve given up driving, but on more and more of their trips, they’re able to walk, bike or transit.”

Upgrades to cycling and pedestrian networks, increases to bus service and a spike in gas prices are some of the factors affecting people’s habits of how they get around the city, concluded the report on the survey, which is now posted on the city’s website.

LaClaire said congestion and longer commute times for vehicles may also be at play in why people are choosing other modes of transportation.

Vehicle trips are getting slower for motorists because of population growth, he said, noting more people translates to more signal and pedestrian crossing lights needed across arterial roads.

He pointed to the ongoing development in and around the growing Olympic Village neighbourhood as example.

”We can expect to see slower travel times for cars, even though there’re fewer cars,” said LaClaire, noting the city installs an average of 10 signal lights per year, the most of which are for pedestrians.

The data from the survey showed a four per cent decrease in auto trips (three per cent for a driver, one per cent for a passenger) compared to results of the 2017 survey.

In addition, participants indicated they drove fewer kilometres—2.9 per cent—than the previous year. LaClaire noted the decrease translates to savings in fuel, a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and obvious health benefits.

The survey did not include trips of commercial drivers, including those who drive trucks, buses and taxis. No tourists or non-Vancouver residents participated in the survey.

Survey participants living in nine “transportation zones” across the city recorded a personal trip diary on a weekday between Sept. 25 and Dec. 19, 2018.

A trip constitutes, for example, a person walking to the library. A second trip would see that person then walk to the grocery store. A third trip would be that person walking home.

Participants are encouraged to be part of the survey each year so travel behaviour can be tracked from year to year. A total of 1,590 people from the 2017 panel returned for last fall’s survey. Only 25 per cent remain from the initial survey in 2013.

The increase in walking, cycling and transit trips comes despite the region’s population continuing to grow by 30,000 to 40,000 residents every year.

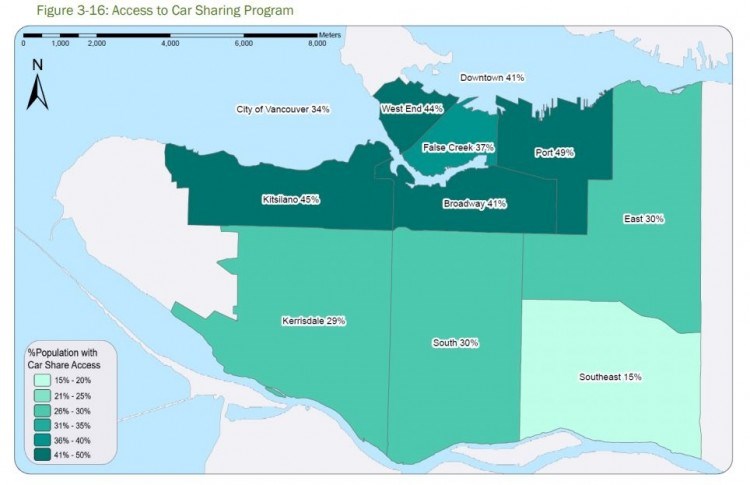

Percentage of survey participants with car share memberships. Image courtesy McElhanney

That growth has come as the Canada Line opened in 2009 and the city allowed bike and car share services to operate in Vancouver. In fact, there are more car sharing vehicles per capita in Vancouver than in any other city in North America.

Car sharing is up, with 34 per cent of residents having a membership and 30 per cent of those surveyed saying they either sold their car or didn’t buy one because of the service.

The membership in car sharing is up from 31 per cent in 2017 and 29 per cent in 2016. It was 13 per cent in 2013.

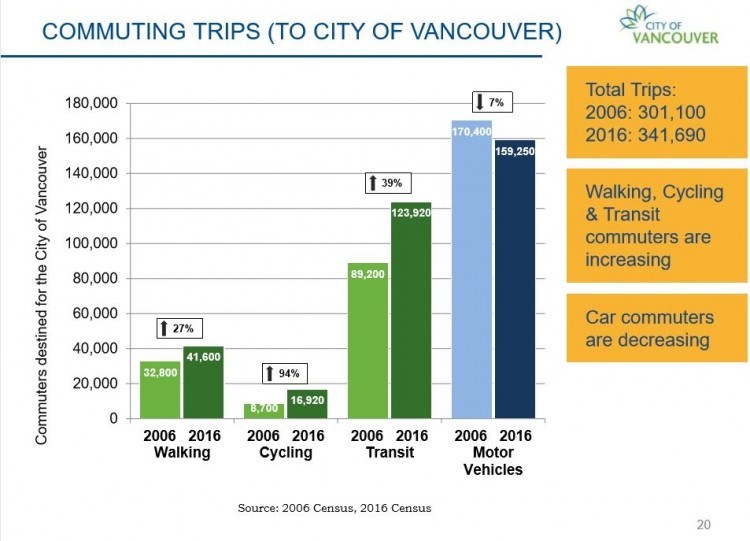

Census data, which the city included in its April 18 briefing to reporters on the survey results, tracked commuters destined for Vancouver.

Commuting trips destined for Vancouver. Image courtesy City of Vancouver

The data showed 159,250 people used a car in 2016 compared to 170,400 in 2006. That’s a decrease of seven per cent.

For the same period, transit ridership increased from 89,200 people in 2006 to 123,920 in 2016.That’s an increase of 39 per cent.

Cycling went up 94 per cent and walking by 27 per cent over the same 10-year period. The city didn’t immediately have the breakdown of where commuters began their journeys, although the opening of the Canada Line in 2009 and Evergreen Line in 2016 suggest residents from the suburbs are connected to the uptick in transit ridership.

Census data collected for Vancouverites-only showed similar patterns over 10 years in car use (a 11 per cent decrease), transit use (34 per cent increase), cycling (101 per cent increase) and walking (28 per cent increase).

Commuting trips to downtown Vancouver from outside the city saw a three per cent decrease in motorists, a 44 per cent increase in transit, a 52 per cent increase in cycling and no increase in walking.

The city contends downtown parkades are, on average, 65 per cent full.

The survey results were released the same day city staff released a report that recommends city council adopt “six big moves” and 53 “accelerated actions” to fight climate change in Vancouver.

One of the “moves” is to have two-thirds of trips in Vancouver made by walking, biking or transit. LaClaire said the survey results show the city already surpassed its earlier goal for 2020 to have half the trips in Vancouver made by these three modes.