It is emblematic of the world’s addiction to plastic and the challenge of reducing our reliance on it.

An environmentally conscientious fast-food restaurateur who wants to switch from single-use plastic utensils to biodegradable ones can easily find any number of purveyors online that sell utensils made from cornstarch.

At least one company will ship these utensils individually wrapped – in plastic. Polypropylene, to be precise, which can be recycled, but which also could end up in a landfill somewhere.

A biodegradable fork wrapped in non-biodegradable plastic symbolizes the challenge for governments around the world, including Canada, that are now moving to ban single-use plastics.

Plastic is so useful, so cheap and so ubiquitous, phasing it out may prove nearly as challenging as phasing out fossil fuels.

In fact, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates the global demand for oil and natural gas will increase over the next couple of decades, not because of increasing demand for gasoline and diesel – which is expected to peak in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries – but because of a soaring demand from the petrochemical industry.

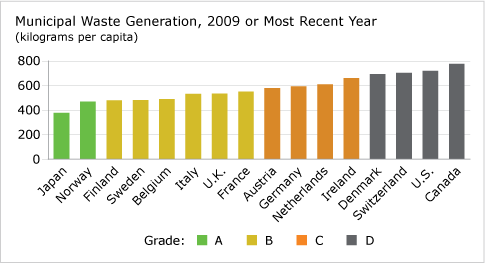

An IEA report on petrochemicals notes that Canada and South Korea are the world’s biggest per capita generators of plastic. Canada appears to be one of the world’s most wasteful countries. It produces more municipal waste per capita than any other country in the OECD, according to the Conference Board of Canada.

According to the Smart Prosperity Institute, of the 3.8 million tonnes of plastics Canadian consumers generate each year, only 12% is recycled.

“Broadly speaking, Canada does not do a good job when it comes to waste generation,” said Joanne Gauci, senior policy adviser at Metro Vancouver and the National Zero Waste Council. “We really have to work across sectors to prevent waste in the first place.”

Canadians may not have given much thought to the country’s waste problems until they recently began reading stories about garbage being sent back to Canada from the Philippines. They may be paying more attention to the problem now, however. A recent Nanos poll found 56% of Canadians support the Justin Trudeau government’s ban on single-use plastics.

Federal Environment Minister Catherine McKenna said there are economic benefits to reducing waste through government bans and extended producer responsibility (EPR) programs similar to the one that has been in place for several years in B.C. and has stimulated new business ventures.

She cited Merlin Plastics as an example of a business created as a result of B.C.’s EPR program.

“We have the opportunity to generate billions of dollars in revenue,” McKenna said. “It’s estimated that we could create approximately 42,000 jobs. And there’s a climate-related piece, which I think is important. We could reduce potentially close to two million tonnes of carbon pollution.”

Keeping it in our own backyard

Much of Canada’s waste could be recycled but isn’t, and it is becoming increasingly difficult to deal with it.

A lot of it has ended up being exported to Asia. But China and other Asian countries have been cracking down on waste imports. As a result, some municipal landfills in Canada are filling up, and it is difficult to build new ones.

So how can Canada do a better job of dealing with its waste in its own backyard?

For starters, the Canadian government has stopped issuing export permits for non-recyclable trash to other countries.

“We tightened up the regulations … to make sure this doesn’t happen again,” McKenna said.

But the Malaysian government claims it did happen again. It too now wants to return non-recyclable waste to several countries, including Canada. In the recent Malaysian case, waste exporters in Canada, Australia and the U.S. may have been circumventing the rules and co-operating with unauthorized importers in Malaysia.

Proponents of a circular economy say the solution to the waste produced through the hyperconsumerism of developed economies is to “close the loop” and reduce the amount of waste coming into – or being produced by – an economy, and to do a better job of recycling what can’t be reduced.

Too much of what global consumers buy is packaged in non-recyclable plastic, and it’s often unnecessary or excessive.

Plastic water bottles are recycled, for example, but the plastic shrink wrap that a case of bottled water may come in could likely end up in a landfill or incinerator. And the packaging for some electronics may contain more plastic than the product itself.

In June, the Trudeau government announced a ban on single-use plastics, which goes into effect in 2021. It will include plastic shopping bags, drinking straws and utensils. Asked how much waste her government estimates could be reduced as a result, McKenna couldn’t say.

“We do know that we’re using up to 15 billion plastic bags every year,” she said, “and close to 57 million straws.”

A single-use plastics ban is still a long way from the zero-waste aims of the circular economy approach now taking shape in Europe, however. The European Union recently formally adopted a circular economy strategy, and pressure is sure to grow on other western countries to follow suit.

A circular economy emphasizes the “reduce” part of the “reduce, reuse, recycle” equation.

“It’s a system change,” Gauci said. “It’s across the economy as a whole. If you think about it as a consumer, what it really means is we’re designing waste out of the system so there’s not that much to deal with at the back end.”

But not even Gauci thinks Canada is ready to follow Europe into a full circular economy just yet.

“We aren’t Europe; we aren’t the U.K. Our geography and our complex jurisdictional environment are factors that we need to consider.”

That doesn’t mean Canada can’t adopt some elements of circular economics. It could, for example, expand EPR programs to cover materials that could be recycled but aren’t yet. Even the Conservative Party of Canada – not exactly known for its environmental zeal – contemplates a national EPR program in its campaign platform.

EPR is essentially a levy charged to the producer – and ultimately paid for by the consumer – on consumer goods, the revenue from which helps pay for recycling programs. B.C. was the first province in Canada to implement an EPR program and consequently has a much more robust recycling system than some other provinces.

According to Recycle BC, British Columbia has a residential (i.e., household waste) diversion rate of 78%. In other words, only 22% of the waste produced by B.C. households ends up in landfills. That is from the residential sector alone, it should be noted, and does not include the commercial and industrial sectors.

In addition to its ban on single-use plastics, the Trudeau government wants to see rates of recycling increased in Canada, although a national EPR program does not appear to be in the cards. Rather, the Trudeau government wants to set targets for recycling and waste reduction, then leave it to the provinces to design programs to try to meet them.

“I think we’d like to go from 9% to 90%,” McKenna said. “And I think that’s attainable if you have a more rational system.”

How Canadian businesses are reducing their waste

Businesses generally don’t like new regulations, taxes or levies. But a number of big businesses operating in Canada – ones responsible for producing a huge amount of consumer waste – are starting to embed circular economics in their own operations.

Businesses belonging to the Circular Economy Leadership Coalition include Unilever Canada, Ikea Canada, Loblaw Cos. Ltd. (TSX:L) and Walmart Canada. All have adopted their own circular economy strategies.

Walmart Canada, for example, has committed to zero landfill waste by 2050. It’s own internal charter on plastics commits the company to:

•eliminating PVC and polystyrene packaging in Walmart brands;

•eliminating single-use plastics in its cafeterias;

•eliminating unnecessary plastic packaging in its own brands; and

•reducing plastic bags at its checkouts by 50% by 2025.

Ikea Canada has already taken steps to ban plastic straws in its cafeterias and has a new “sellback” program in which customers can take their old Ikea furniture back for in-store credit.

“From a design perspective, we’re incorporating more recycled and recyclable materials into our product development,” said Melissa Mirowski, sustainability lead for Ikea Canada.

“We’re removing waste from the supply chain by using it to develop new materials as well. And at the end of life, which is the retail side of things, it’s about ensuring that our customers have services provided by us to help extend the life of our products.”

Circular economics’ implications for business will be among the topics discussed when Canada hosts the World Circular Economy Forum in 2020.