Commercial fishermen in B.C. are sending out an SOS following last year’s disastrous salmon season that has already sunk some boat owners.

The union representing commercial fishermen says years of Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) “mismanagement” pushed some commercial fishermen to the brink, and 2019 pushed them over.

“Hundreds of fish harvesters are facing financial ruin after decades of fisheries regulation mismanagement,” said Joy Thorkelson, president of the United Fishermen and Allied Workers’ Union.

“Fishermen are retiring from the fishing industry en masse. I was in the office in Vancouver last week and we had six people who were active fishermen come in and said they’re just hanging up their skates. Their boats are up for as cheap as they can sell them.”

The union has been lobbying Ottawa for financial aid since August, when it became apparent that a massive run failure was likely, but so far their calls have fallen on deaf ears.

And to make matters worse, no one is sure what kind of impact last year’s rock slide at Big Bar in the Fraser canyon will have on future sockeye and chinook runs.

In 2019, the total number of salmon – all species – caught by the commercial sector in B.C. was just 629,000. That is the lowest catch in 70 years, according to Unifor.

Even in 2008, a disastrous year for Fraser River sockeye, the total commercial catch for B.C. salmon (for all species) was 1.7 million, and that was considered one of the worst seasons on record.

It might not have been quite so bad in 2019 had the Pacific Salmon Commission not been surprised by a fairly strong, unanticipated return of pink salmon, which slipped up the Fraser River before commercial openings could be approved.

As a sign of just how bad things got in 2019, Phil Young, vice-president of fisheries and corporate affairs at the Canadian Fishing Co. (Canfisco), said the most successful seine fishermen were the ones who didn’t go fishing.

It costs about $1,200 for a seine licence, and mandatory logbooks cost $400 to $700, depending on the vessel and fishery, Thorkelson said. Those are fees that have to be paid to the federal government even when there are no commercial openings. So seine fishermen who didn’t bother getting licences and logbooks limited their losses.

“For our fleet, the guys that did the best last year were guys that never went out fishing,” Young said.

And some may not bother going out in 2020, either.

Thorkelson is supposed to represent seine fishermen in collective bargaining. Except she’s not even sure if there will be anyone to represent.

“I can’t bargain the collective agreement because it’s hard for me to find enough fishermen that say they’re going to go back seining next year,” Thorkelson said. “Everybody I’ve been phoning for a meeting is saying, ‘Well, I’m not fishing next year – I’ve quit.’”

At the very least, she thinks fishermen who paid for federal licence fees and logbooks should be reimbursed, since most of them never put a net in the water in 2019.

When Thorkelson appealed to former fisheries and oceans minister Jonathan Wilkinson – now environment minister – for emergency aid, she got the Ottawa runaround.

“We started this on August 2,” Thorkelson said. “We knew there was a run failure coast-wide by August 2. He wrote back and said, ‘There is no emergency assistance program – talk to EI.’ And then the EI minister answered back and said, ‘talk to Wilkinson – this isn’t our issue.’”

The union has persisted with the new minister, Bernadette Jordan, who appears to be even less responsive than Wilkinson was.

“We’ve sent her so many letters now,” Thorkelson said. “I can’t even begin to count the number of letters that have been sent asking for a meeting, and she hasn’t even replied to them.”

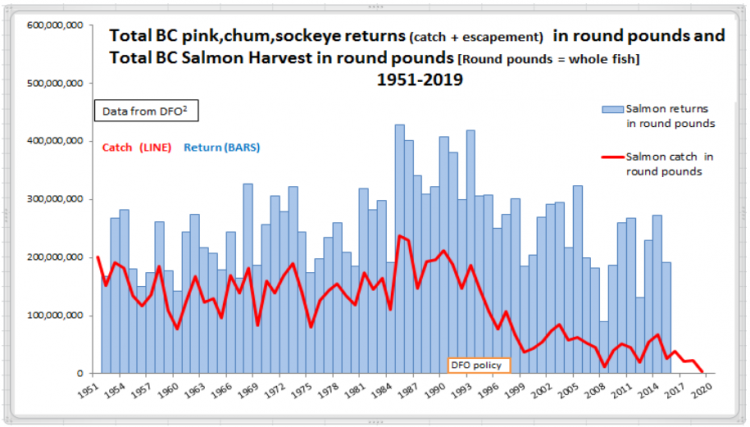

Since the mid-1990s, the commercial sector’s harvest of Pacific salmon has gradually, and continuously, declined, despite the fact that overall abundance remained relatively stable.

There had been years when certain stocks declined sharply, as was the case for Fraser River sockeye in 2008 and 2009, which crashed, only to rebound spectacularly in 2010.

But in 2019, Pacific salmon stocks of all species pretty much crashed throughout the southern range, including Japan. For some fishermen, it was the last nail in the coffin.

“The federal government created a commercial fishing economy so precarious that when the salmon collapsed this year, the industry went with it,” Unifor national president Jerry Dias said. “Commercial salmon fishing may never recover.”

A recent Unifor report shows that the B.C. commercial salmon harvest has consistently declined since the mid-1990s.

“The report shows that, until 2019, the overall number of salmon returning to B.C. remained stable for 63 years, yet the commercial fishing catch limits set by the federal government declined sharply in the mid-1990s without justification,” a Unifor press release states.

“Artificially low limits together with dropping landed value combined to undermine the livelihoods of the entire commercial fishing fleet on British Columbia’s coast.”

The Unifor study was based largely on a study published in 2018 by Greg Ruggerone and James Irvine, who collated salmon catch and escapement data from all Pacific salmon-producing regions dating back to the 1920s to estimate abundance of sockeye, pink and chum salmon.

That study concluded that, as of 2015, Pacific salmon were more abundant than they have ever been. However, that abundance is largely in northern ranges – Alaska and Russia – and two species, pink and chum salmon, account for the lion’s share of that abundance.

Irvine, a DFO salmon oceanographer, cautioned that the study he co-authored only went up to 2015, and since then there have been some sharp declines in abundance. So 2015 may have marked a peak in Pacific salmon abundance.

“You can, I think, make the point that the catch has declined at a steeper rate than the escapement,” Irvine said. “But I think you have to say that, in B.C., the abundance of salmon has declined. There’s no doubt that the abundance of salmon is less than it used to be, and it’s much worse when you go down to Washington, Oregon and California.”

He also noted that 40% of the abundance in the Pacific that he and Ruggerone quantified was hatchery fish, mostly from Alaska, Russia and Japan. They believe such large numbers of hatchery pink and chum salmon may have had a negative impact on other stocks.

While there are many factors that affect salmon abundance, there is growing evidence that climate change may be the single most important factor. This would account for the fact that northern stocks have been robust, while abundance has declined in all regions of the South, including B.C., Japan, Washington, Oregon and California.

Thorkelson is therefore pressing for a climate change adaptation plan. She points to Newfoundland, where climate change may have benefited some fishermen.

The Atlantic fishery was devastated by the collapse of the Atlantic cod in the early 1990s, but warming ocean waters appear to have brought them something even more profitable than cod: Lobsters.

It’s not yet clear if B.C. fishermen will also benefit from a species shift from ocean warming, though there are signs that certain species of tuna have been gradually shifting their range to more northern waters, including the B.C. coast, and will continue that move as the Pacific Ocean becomes warmer.

Thorkelson said a climate adaptation plan might include a strategy that allows fishermen who relied primarily on salmon to shift to other species, like tuna.

For those who remain in the fishing industry, a multi-licence fleet will be needed, she said, so that a single licence would allow the boat owner to fish for a variety of species, as is done on the East Coast.

“You could purchase multi-licences now, but you are probably going to owe millions in licence and quota fees,” Thorkelson said. “So that needs to be looked at.”

Federal Fisheries Minister Jordan did not respond to an interview request from Business in Vancouver.