The local Chinese restaurant industry’s request for tax relief for businesses that have been hit by low turnout due to fears over the COVID-19 coronavirus makes sense if the proper accountability measures are taken, experts say.

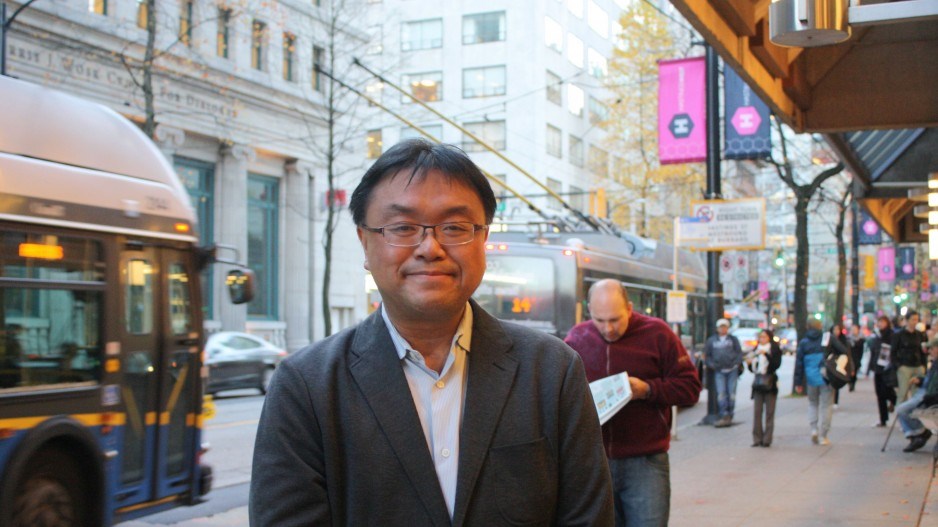

Andy Yan, director of the City Program at Simon Fraser University and one of the region’s leading urban-planning experts, said the request for financial support makes sense and has precedents. He pointed to Chinatown businesses in New York, which sought government support after the 9/11 terrorist attacks devastated the neighbourhood.

“I think part of it is that it parallels concerns about natural disasters, and you could see a parallel in terms of what type of support that might occur,” Yan said, noting that governments may look at bridge loans or low-interest loans instead of outright tax relief as options.

The response comes after a February 21 news conference in Richmond where Metro Vancouver Chinese restaurant representatives called on the federal, provincial and municipal governments to provide embattled establishments with more support as fears over the spread of the virus have resulted in patrons forgoing restaurant meals.

Restaurants have reported business dropping by as much as 80% in some cases since the coronavirus outbreak was first made public on January 20 in Wuhan, China. They have called for Ottawa to step in and provide relief in the form of temporarily reducing the GST for restaurateurs and initiating more proactive quarantine procedures for people recently returning from China.

“We are asking for this because the outbreak would have a huge impact in our industry if it’s left unchecked,” Canada Catering Association president Charlie Huang said. “We will do everything in our power to ensure public safety ... but we need more government support.”

However, Yan emphasized that the process must be based in fact and divorced from emotion.

“It was one of the elements of 9/11 recovery that you did have some support available, but it was on the premise of transparency. Folks had to provide documentation of their losses. A blanket handout is not how this works; like an insurance claim when a natural disaster hits, you have to show proof.”

However, Yan noted the complexity of restaurants as locations that intersect private business, public community space and local economic engine lines – so how government defines an affected area will be key in ensuring a transparent and fair support package for those affected.

Henry Yu, principal at the University of British Columbia’s (UBC) St. John’s College graduate school and a leading academic on Chinese-Canadian history and issues, agreed that defining the affected area is key.

He added that the task might not be as straightforward as identifying Chinese restaurants alone.

“How the restaurant owners have self-organized is one thing. How businesses are being affected is another. My sense, if you are looking at a place like Richmond where large portions of the population is ethnic Chinese, if people see an inordinate effect on businesses across the board because people aren’t going out to public places as much, that has to do with the demographics of Richmond.”

Yu added that, ultimately, whether a government organization decides to proceed is historically based on politics, not social policy.

“If you are a planner in a city and you are seeing a problem with businesses there, I would attack it like any other thing, which is by asking this: how important is it that we support businesses through a time of financial crisis? Is it part of our policy? Is it politically important to the people who make the decisions and will have to wear it during the next election?”

Yu was less receptive about the Chinese restaurant owners’ request for a more stringent quarantine policy for those returning from China, similar to the approach taken by countries like the United States and Australia.

He noted that he has seen his international students returning from China self-quarantine for the sake of others – showing a “fear for” rather than a “fear of” being an important distinction.

“We tend to judge people morally on what people do during times of crisis, and that’s another historical lesson,” he said. “Something that may look like a good idea during a period of panic may not look so good when the panic is gone.

“If they want some kind of economic or financial relief – if they are looking for specific things that will help them as restaurants in this time of crisis – I don’t have a problem with that. I don’t think we should listen to them for quarantine advice or for what to do with travellers from China.”

The concern among the Chinese-Canadian community, however, is very real, said Yves Tiberghien, director emeritus of UBC’s Institute of Asian Research. In his conversations and social-media tracking with his Chinese contacts, as well as family and friends, Tiberghien said the uniqueness of COVID-19 means that an abundance of caution may be warranted.

“On the Canadian side, without being a fear monger, so far Canada has been one of the most lax countries when it comes to this topic,” he said. “The problem is that we still have a lot of human flows; there are still a lot of people who travel, and this is a very, very treacherous virus. So I don’t know if we are fully ready yet. Given the number of people travelling back and forth and the nature of this virus, I hope … that what we are doing – asking people to self-quarantine for 14 days if they show any symptom – will be shown to be wise. But we need to be ready if we see a sudden spike in cases in Canada, because it is a difficult virus.”