Virtually every real estate development in British Columbia now requires an investigation by Qualified Environmental Professionals (QEPs) to qualify the project for an environmental development permit before construction can proceed.

The permit ensures that the dirt is free of contaminants and that the development will not interfere with wildlife, watercourses and myriad other environmental issues.

But, according to developers and QEPs – applied scientists or technologists, professional biologists, agrologists, foresters, geoscientists or engineers who provide services within their area of expertise – the extensive and expensive studies are often being overruled by city planners who have their own interpretation of the regulations.

This is frustrating but also understandable, said biologist Harm Gross, a QEP and president of Burnaby’s Next Environmental Inc. who has been conducting environmental studies for years.

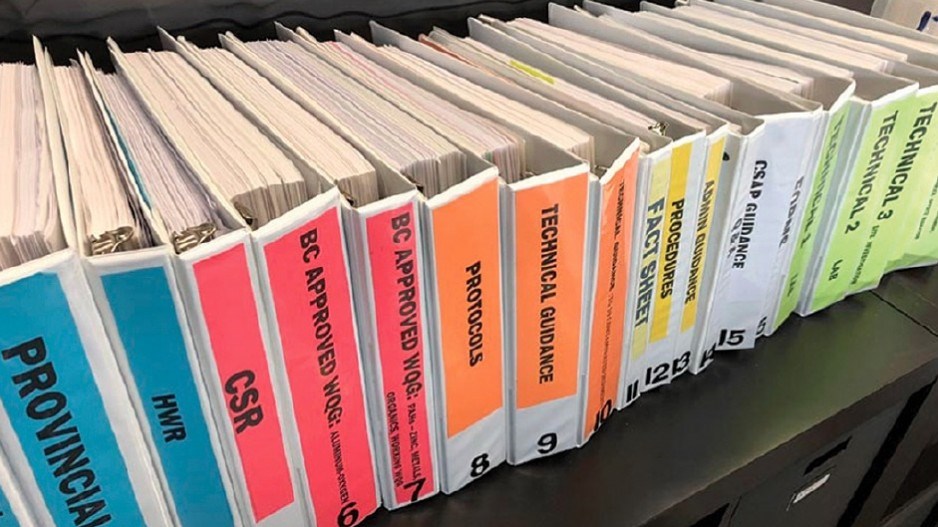

Gross notes that B.C.’s Contaminated Sites Regulation now covers 10,000 pages in scores of volumes, and there are 38 other bits of provincial and federal legislation that relate to wetland conservation, including the Water Sustainability Act, the Agricultural Land Commission Act, the Transportation Act and the federal Fisheries Act.

The federal government’s No Net Loss Policy can also apply to protection of fish, migratory birds and federally listed species at risk.

“It’s easy to see that there is a lot of legalese to draw on when a municipal authority argues the QEP is wrong,” Gross said.

He added that the issue is further complicated today by the complexity and scale of mixed-use development, much of which is being done from brownfield sites that require rezoning, such as from industrial to residential.

There is a lot at stake.

A civic ruling that a dead-end drainage ditch is actually a potential fish-bearing stream can carve a 60-metre wide no-go zone through the centre of a site, making it impossible to develop.

None of the real estate developers that Business in Vancouver spoke to would go on record with their concerns.

“I have a permit application in process, and I don’t want it to go to the bottom of the list,” explained one Fraser Valley residential developer in what was typical response.

Developers say that any needless extra costs they face are passed on to consumers, whether new home buyers or commercial tenants. Owners, who may have paid property taxes for decades with the anticipation of profiting from their land, have no recourse from a wrong decision.

“I have seen landowners in tears,” said Joe Varing, a Surrey real estate agent who specializes in land transactions.

A major developer told BIV of a 2018 conflict over a roadside drainage ditch that City of Surrey planners designated as part of a wetlands area, in direct conflict with the findings of the developer’s QEP, a decision that had been endorsed by the province.

“It cost us an 18-month delay and a huge amount of money before it got resolved,” the developer said.

Other developers said they have run into similar conflicts in the Township of Langley, Delta and Squamish.

Some noted that a younger generation of city planners are much more zealous when it comes to environmental interpretations.

“The pendulum appears to have swung from one extreme – mass wetland destruction – to the other: preservation of all land that can be wetted. It is easy to understand why developers feel slighted when a city regulator rejects an expert’s opinion, seemingly out of hand,” Gross said.

The issue has become so contentious that the Urban Development Institute (UDI) emailed its developer members in April asking if they had been affected. A UDI staffer, who asked not to be named, said the institute had received a substantial response.

All of developers with complaints about what they perceive as arbitrary decisions at city hall declined to speak publicly.

Surrey, which is setting up zoning and density development for the proposed SkyTrain extension corridor along the Fraser Highway towards Langley, is aware of the conflicts.

Representing Surrey Mayor Doug McCallum on a panel of Fraser Valley mayors convened by the UDI in Langley this year, Surrey Coun. Linda Annis said the city wants to bring “clarity” to the development process.

She acknowledged that the strict enforcement of setbacks for water and other environmental conditions may cause issues for landowners and developers, limiting the amount they can build or affect a project’s financing.

“Absolutely. But as developers are negotiating the purchases of these properties, that’s something that they should be taking into consideration,” she said. “Where it gets muddied is if we’re not clear what the environmental setbacks needs to be, and I think Surrey now is doing a pretty good job of that.”

On April 30, the City of Surrey announced it was exploring ways to help large real estate developments in the city, including “expediting the review and processing of environmental development and erosion sediment control permits.”

Varing voiced some sympathy for city planners. He noted that strict environmental measures in Metro Vancouver have helped lead “to some of the best real estate developments in the country.”

“They are just doing their job,” the president of Varing Marketing Group said. “It is just part of the process that we all have to work with.”