When a tailings pond dam at the Mount Polley copper-gold mine collapsed in 2014, it was one of the worst mining disasters in recent memory in Canada.

But it was only one of four such dam failures around the world that year, including one in Brazil that killed two workers. In 2019, there were six tailings pond failures, including one in Brazil that killed more than 250 people.

On average, there have been two or four tailings pond ruptures every year around the world over the last decade, with a relatively high number of them occurring in places like Myanmar, Brazil and China.

And with even more mines to be built in the coming decades to meet the demand for minerals and metals from a world switching to renewable energy and electric cars, that raises the spectre of increased tailings pond failures around the world, according to Safety First a new report by Earthworks and MiningWatch Canada.

“Tailings facilities, which contain the processed waste materials generated from mining metals and minerals, are failing with increased frequency and severity,” the report warns.

The report calls for alternatives to wet tailings ponds or, where that is not feasible, better dam designs.

“The safest tailings facility is the one that is not built,” it states.

Whenever possible, wet tailings pond dams should be avoided by using filtered tailings storage, otherwise known as dry-stack tailings, the report recommends.

But there can be environmental trade-offs with filtered tailings, which are mine tailings that have been “dewatered” to create a semi-solid. They are not really dry, but more like a moist material like partially dried cement.

The whole point of storing mine waste (finely ground rock left over after valuable metals have been extracted) under water in a tailings ponds is to avoid acid rock drainage, which can occur when metals in waste rock are exposed to air and then water. Acid and toxic compounds can then drain into local waterways when it rains.

So, filtered tailings may avoid the loss of life and property that can result from a wet tailings pond rupture, but in regions with high precipitation, it can pose additional challenges with managing acid rock drainage.

Even so, when an expert panel was struck to investigate the Mount Polley tailings pond failure, it recommended the use of filtered tailings for future mines.

“They said there’s no overriding technical impediments to more widespread use of filtered technology,” said Jan Morrill, Earthworks’ international mining campaigner. “So, yes, it does require additional engineering considerations, but the expert panel that looked directly at Mount Polley said filtered tailings should be used more widely in order to promote safety.”

She added that it would be difficult to implement filtered tailings at an existing dam like Mount Polley. But for all future mines, the report recommends filtered tailings.

When filtered tailings are not an option, at the very least better dam construction needs to be required by regulators, Safety First states.

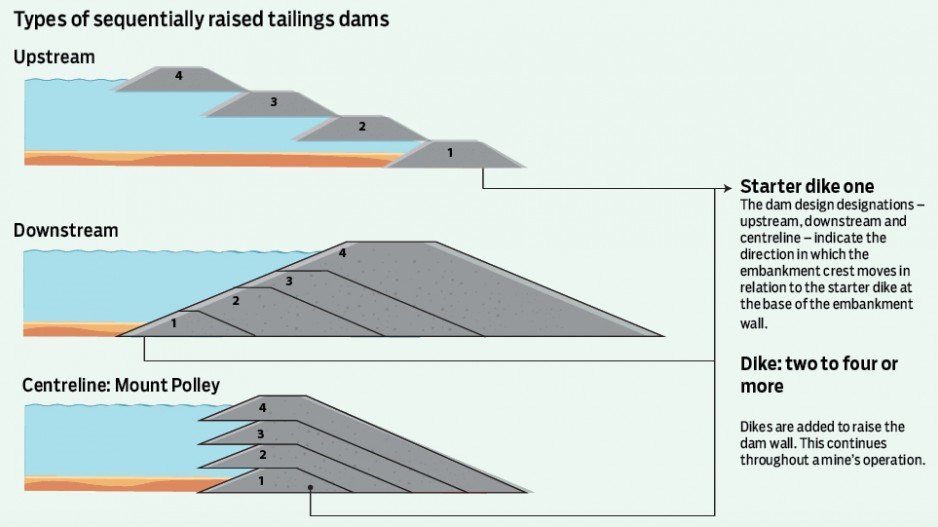

There are three types of designs: upstream, downstream and centreline. This refers to the orientation of the dam embankments not the physical location of the tailings pond in relation to the mine, community or lake. The upstream design is considered the least secure.

“The use of upstream dams must be banned in favour of centreline and downstream dams, which are much less vulnerable to all mechanisms of dam failure,” Safety First recommends.

The Mount Polley Tailings pond was a modified centreline design.

When the Mount Polley mine was first being designed, Imperial Metals (TSX:III) CEO Brian Kynoch said drystack tailings were considered. But he said a water dam had to be built anyway, because large amounts of water are needed for the milling process. So the company decided it might as well use it for tailings storage.

Kynoch said the best solution would have been to pump the tailings into Quesnel Lake, which is North America’s third deepest lake.

Despite the relatively “clean” geochemistry of the ore, the prospect of putting mine waste in a lake would have been met with a public outcry.

“Most experts, I’d say, would tell you that that’s probably the best thing to do. But it’s a very hard-to-permit solution,” Kynoch said.

However, that’s what happened anyway: tailings at the bottom of a lake and a public outcry.

According to the expert technical panel that investigated the Mount Polley incident, the dam’s design wasn’t so much the problem as the foundation it was built on. It might have still collapsed, regardless of how the embankments were built.

The tailings pond dam sits on a layer of glacial till, which is consolidated everywhere except under the portion where the dam collapsed. In that area, the glacial till was less consolidated and was therefore unstable.

Even though the volume of water built up behind the dam was not deemed to have caused the collapse, it did exacerbate the damage.

Imperial Metals had expressed concerns to B.C.’s Ministry of Environment over the volume of water that had built up behind the dam. It had been asking for a water discharge permit to reduce pressure on the dam, and even warned the ministry in January 2014 that, without being able to discharge water, “there exists a three-year timeframe during which storage will become geo-technically problematic.”

The company warned that pressure was building up behind the dam, risking overtopping.

“Six years to get a discharge permit,” Kynoch said. “Six years of study, and then they gave us a permit that wasn’t big enough.”

That is, the permit did not allow enough water to be discharged to attain a negative water balance in the dam.

An expert panel investigating the dam’s failure concluded that the collapse was the result of a weak, soft layer of glacial till that had not been detected by engineers when the dam was first designed and built in the mid-1990s.

That may explain why Imperial Metals was never charged for the dam’s failure, and why the engineering firm responsible for the dam’s design and maintenance eventually settled out of court after Imperial Metals sued it for $108 million. Three engineers who had been responsible for the dam’s maintenance are facing disciplinary hearings.

Just last week, a report commissioned by the BC First Nations Energy and Mining Council noted that the regulatory environment around tailings ponds in B.C. have improved since the Mount Polley incident, but warns that more needs to be done to avoid future dam failures.

It even suggests some mines should be shut down.

The report notes there are a dozen new mine proposals in B.C. and raises particular concerns over the massive KSM mine proposal, which the report says would place a massive tailings pond dam above the Bell Irving-Nass watershed.

“While transparency of decisions by mine operators has been improved by recent regulatory reforms and stakeholders now have more access to information than in the past, more needs to be done to enable direct community involvement regarding design, management and monitoring to ensure tailings dam safety,” the report states.

“But in spite of B.C.’s mine law reforms after Mount Polley, the elephant in the room still remains: should the B.C. government allow the development of new tailings dams upstream of communities and should those that currently exist be closed down?” •