Vancouver Mayor Kennedy Stewart successfully introduced a motion Wednesday to double the empty homes tax to 3% next year after a new report from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) showed a significant increase in the supply of rental condominiums in 2019.

The empty homes tax, which was to be set at 1.5% for the 2021 tax year, was implemented by the previous council to encourage property owners with vacant homes to open them up for rent in Vancouver rather than be taxed.

Stewart told council the CMHC data shows how the empty homes tax in combination with business licensing requirements and restrictions for short-term rentals such as Airbnb is having the desired effect on moving vacant condominiums onto the rental market.

“There is still a lot of work to do, however, so increasing the tax to 3% should have the impact of accelerating moving these condos back into the rental market or, in some cases, people will sell them to folks that will actually live in them,” said Stewart, whose motion passed with NPA councillors Lisa Dominato, Melissa De Genova and Sarah Kirby-Yung in opposition.

Analysis from the CMHC shows 8,824 of 11,118 new units were converted to long-term rental in the Metro region, with 58% or 5,097 located in Vancouver. By comparison, Vancouver is home to 37% of the region’s condominium housing.

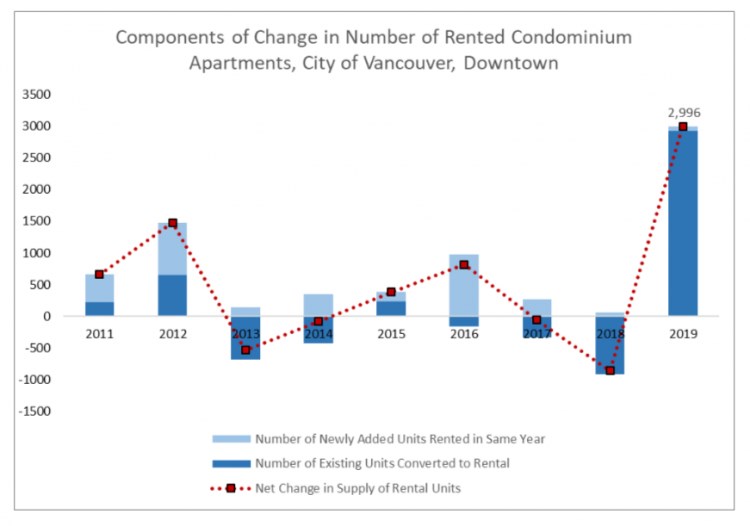

That conversion rate to long-term rental was further concentrated downtown, with almost 3,000 units converted to rental.

“Following several years of losses of existing units from the long-term rental market, the change in market participation in 2019 in downtown Vancouver was likely impacted by the combination of housing policies introduced to encourage the rental of condominiums to long-term tenants,” the report said.

“In addition, the number of units converted exceeded the number of condominium sales in the area during the period. This means a significant number of conversions were undertaken by existing owners, even if all condominium sales were to investors who then rented the units long-term.”

This graph shows the number of newly added and converted rental untils in downtown Vancouver. Graph courtesy CMHC

Hardwick, who has long questioned the city’s targets to build more market housing, suggested the findings show there is already enough rental units on the market and “it begs the question about the housing emergency.”

“I will agree that we have an affordability crisis in housing, but I hope that we’ll take this not just as an opportunity to increase the vacancy tax — which I support — but to revisit the numbers in the Housing Vancouver strategy and press pause on promoting development until we really know where we really sit on this stuff,” she said. “I feel like a bit of a stuck record on this subject. We need to know where we are. But I am encouraged that these varying changes, including the empty homes tax, the decline of Airbnb and foreign students — in combination — are returning significant numbers back to rental capacity for local renters.”

Overall, across the region, the 11,118 rental units added to the market represented an increase of 18.9 per cent over 2018, with CMHC attributing the uptick to a combination of market factors and housing policies to encourage long-term rental.

The CMHC report said the “record” increase in units was the sum of two parts:

• An increase of 2,294 rental units from new condominiums completed between the 2018 and 2019 survey years. These units were purchased by investors who immediately offered them for rent on the long-term rental market upon completion.

• An increase of 8,824 rental units from existing condominiums that were converted to being offered as long-term rental units in 2019. These units were previously used for other purposes by their owners or changed owners between the two survey years, at which point, the new owner opted to rent out the unit.

Since 2017, various levels of government introduced policies to promote and stabilize the supply of long-term rental condominium units. That has included the city’s empty homes tax, the city’s short-term rentals regulations and the B.C. government’s speculation and vacancy tax.

In Vancouver, a property owner with a second property in the city is susceptible to all three regulations, with the report suggesting these policies created strong incentives for an owner to rent a unit long-term as opposed to leaving it vacant or renting it short-term.

“It is likely that these policies played a role in owners’ evaluation of the best use of their properties, contributing to the supply of condominiums in the region’s long-term rental market,” the report said.

Other factors cited that could have contributed to the increase in supply include strong rental demand and some owners — who made significant capital gains related to price appreciation of their units — choosing to sell.

In turn, new owners may have added units to the long-term rental market that were previously owner-occupied, vacant, or rented short-term, the report added.

Placed in a historical context, the report said it was clear the increase in the supply of rental condominiums in 2019 was “an outlier,” following losses of several thousand existing rental condominiums to other uses in 2016 and 2018.

The CMHC concluded its report saying the pandemic will result in additional changes to both supply and demand in the Vancouver rental market.

“For example, there has been a slowdown in global travel due to the coronavirus,” the report said. “This could cause some additional condominium owners who currently rent their units as short-term vacation rentals to bring their units to the long-term rental market, in the hopes of taking advantage of more stable income and demand.”

Coun. Jean Swanson pointed out she tried to increase the empty homes tax to 3% last year but didn’t get enough votes. While the tax encourages owners to rent properties, Swanson also noted money from the tax — $61.3 million since 2017 — supports affordable housing initiatives.

“If people are rich enough to own an empty house, they’re rich enough to help provide for people who don’t have housing, and we definitely need more money for non-profit housing and this is one way to get it,” Swanson said.

Kirby-Yung pointed out on Twitter after voting against the mayor’s motion that city staff was clear further study was needed before increasing the tax, citing unintended consequences for property owners also subject to the B.C. government’s speculation tax.

“Another point to consider,” she wrote. “It’s rare to see City of Vancouver staff not recommending a tax or fee increase. So when staff suggest holding the line for a year to enable analysis and informed decisions, it’s worth taking note.”

Increasing the empty homes tax to 3% was one of Stewart’s campaign promises when he ran for mayor in 2018. When asked by Glacier Media in September why hadn’t pushed to increase the tax, he replied: “When I made that promise, the province was talking about putting in new demand-side measures, but they hadn’t. So by the time we got to the point where we were making a decision about the empty homes tax, there already were, I think, five new demand-side measures on speculation and vacant homes. So what I thought would be a bit reckless would be to add all that in, and I was worried about the effects on the market.”

Most homeowners in Vancouver are not subject to the tax because it does not apply to principal residences or homes rented for at least six months of the year. However, all homeowners are required to submit a declaration each year.

The non-compliance rate has ranged from 5-10%.

@Howellings