With the glaring exception of Quebec, secessionist movements in Canada have a way of fizzling out, regardless of their intentions and intellectual gravitas. B.C. was briefly part of this trend in 2013. A provincial election resulted in Vancouver Island electing only two of 14 MLAs from the governing party, and a group called “The Province of Vancouver Island” arose.

The group’s website (viprovince.ca) provided a road map for Vancouver Island to achieve a different relationship with Ottawa. By 2018, the plan had been completely abandoned, and the web address is now no longer accessible.

Before last year’s provincial election in Saskatchewan, the Facebook page of the Buffalo Party boasted hundreds of thousands of followers. The party’s candidates ultimately received 11,298 votes, demonstrating that social media “likes” do not translate into tangible political representation.

The proportion of Albertans who believe that their province should become independent has fluctuated in the past few years. When Research Co. and Glacier Media asked in December 2018, 25% of Albertans thought they would be better off as an independent country. By July 2019, just weeks after the provincial election that brought the United Conservative Party (UCP) to government, the proportion rose to 30%.

This month, we asked residents of Alberta, Saskatchewan and B.C. about their appetite for sovereignty under various scenarios. For starters, the outright independence of Alberta is backed by 25% of the province’s residents, consistent with what we found in 2018 and lower than the all-time high registered in 2019.

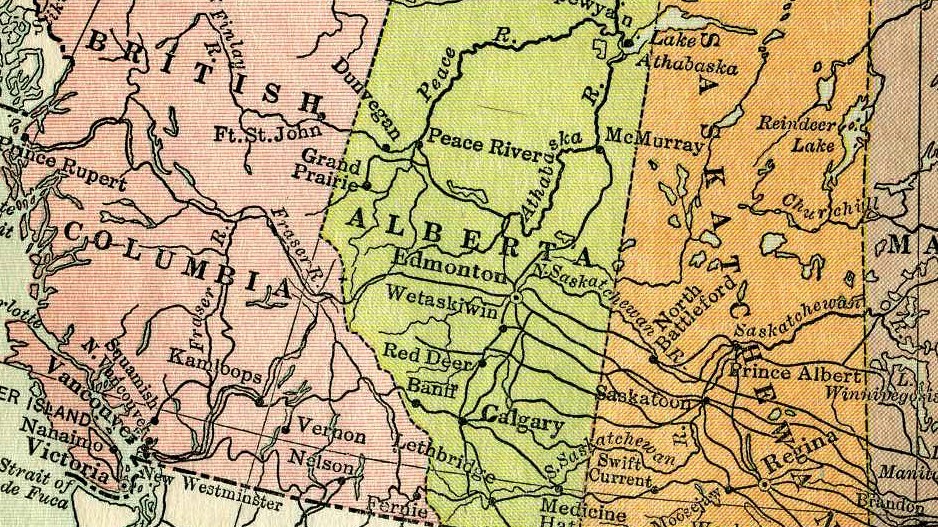

A nation encompassing Alberta and Saskatchewan gets the thumbs-up from 26% of Albertans and 21% of Saskatchewanians. This slightly more popular country combining two provinces that voted overwhelmingly for the federal Conservative Party in 2019 would still be landlocked.

Enter B.C., with its enviable access to the Pacific Ocean. The notion of all three westernmost provinces seeking sovereign status is attractive to 29% of Albertans and Saskatchewanians, but to only 12% of British Columbians. Separation is also decidedly unpopular in British Columbia under two other forms: alone (12%) and with Alberta (13%).

In Alberta, almost half of residents who voted for the UCP (47%) say they would welcome sovereignty nested between Saskatchewan and B.C.

When residents of the three provinces were asked to rate the responsiveness of their provincial administration, Saskatchewan and B.C. post stellar marks (62% and 60%, respectively). In Alberta, only 43% of respondents feel the same way.

There are always situations in which opposition voters will go against the sitting government. While three in five Albertans who voted for the New Democratic Party (NDP) in the 2019 election (60%) deem the current provincial government “unresponsive,” they are joined by 41% of those who voted for the UCP. The base is not as solid as once imagined.

This does not mean that the original catalyst of western alienation – an Ottawa that is oblivious to what happens “out here” – is gone. While 45% of British Columbians consider that the federal government is responsive to their needs, far fewer Albertans (32%) and Saskatchewanians (26%) concur.

For Albertans who voted for the UCP in 2019, the dissatisfaction with the current state of affairs is palpable. Almost half would welcome sovereignty alongside Saskatchewan and British Columbia, and two in five suggest that the provincial administration does not care about their struggles. Flirtations with an uncertain future as an independent nation are a reaction to both Ottawa and Edmonton.

Finally, a proposal for Alberta to join the United States is supported by only 18% of the province’s residents. This idea is promoted by the Alberta USA Foundation, which last summer paid for a billboard in Edmonton featuring Donald Trump. Its online store of hats, T-shirts and mugs is reminder of how easy it is for anything these days to call itself a “foundation” or an “institute.” •

Mario Canseco is president of Research Co.

Results are based on an online study conducted from February 7 to February 9 among 800 adults in British Columbia, 600 adults in Alberta and 600 adults in Saskatchewan. The margin of error, which measures sample variability, is plus or minus 3.5 percentage points for British Columbia and plus or minus 4.0 percentage points for Alberta and Saskatchewan 19 times out of 20.