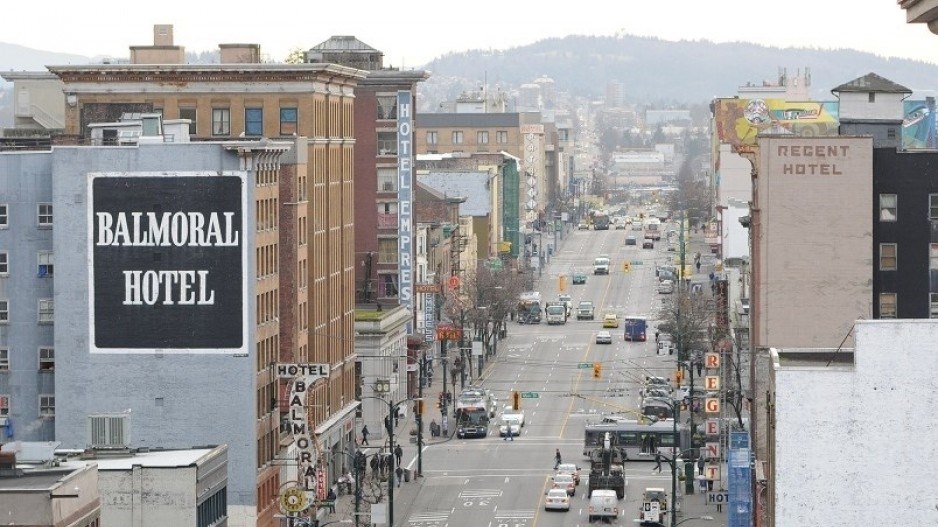

It is, without a doubt, Vancouver’s most desolate strip.

For decades, the five blocks of Hastings Street that run west from the Patricia Hotel at Dunlevy to the Woodward’s development at Abbott have been ground zero for the city’s social problems.

Drug addiction, homelessness and mental illness are on display writ large, with poverty, trauma and hopelessness driving the misery of the many people who live in the neighbourhood.

(Also see: Nine Hastings Street properties to watch for redevelopment)

Such tragedy on the street — further exposed during the pandemic — has led to years of protest, legal fights and calls to mayors, premiers and prime ministers to address the crises.

In response, medication-assisted treatment for drug users has increased, more injection sites have opened and a campaign to decriminalize simple possession of illicit drugs continues.

Welfare rates have improved, more housing and shelters are available and government has committed to additional programs for people living with a mental illness.

Still, the strip churns with despair.

It does so while the real estate along East and West Hastings — some of it dilapidated and boarded up — is increasingly being bought by the B.C. government and the City of Vancouver for social housing.

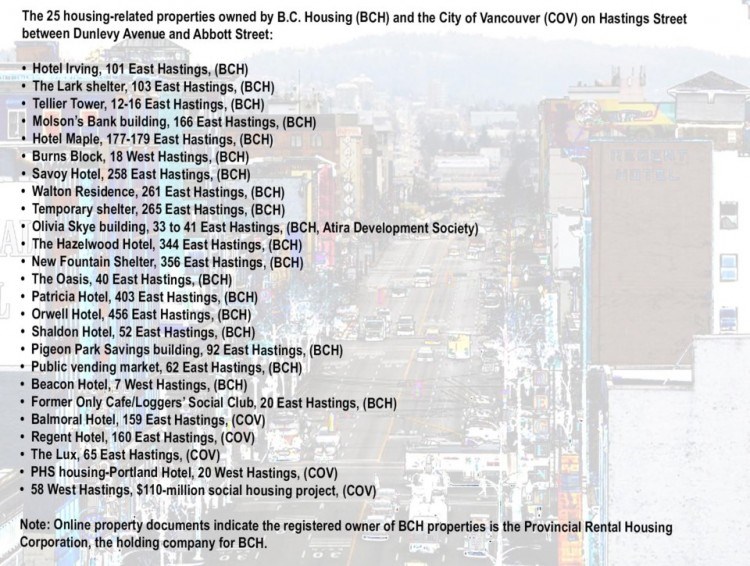

A Glacier Media investigation of more than 90 properties along the five blocks of Hastings discovered the two entities own a combined 25 sites dedicated to current and future housing.

It’s the highest concentration of ownership on the strip.

Who owns the Downtown Eastside?

For the most part, taxpayers do.

So what then is the end goal of the public investments, which ramped up considerably since December 2020 with an estimated $90 million spent to acquire three hotels, a heritage building, a parking lot and a shelter?

The strategy, as imagined and implemented by B.C. Housing and the city, is straightforward: to acquire and redevelop property to provide housing for vulnerable, low-income people.

It is a humanitarian and financially sound response to such grand-scale deprivation in the city’s poorest neighbourhood, they say.

But it is not an approach shared by some current and former property owners on Hastings — and others tied to the real estate industry — who believe the investment is based more on containment of a complex neighbourhood than an effort to diversify and rejuvenate.

While acutely aware of the need to address the crises visible outside their doors, they question whether government investments in social housing and restrictive city policies is the way forward on a tired strip of real estate they say is in need of a facelift.

“How can anybody look you in the eye and tell you that what’s happening down there is a good idea?” said Jon Stovell, president and CEO of Reliance Properties, who sold the company’s Burns Block building at 18 West Hastings in April to the B.C. government for $10.9 million.

“Not only is it not good for the people of the city as a whole, it’s not even good for the people that they’re trying to protect down there. It’s the worst place they could possibly be.”

Source: Public records, BC Housing, City of Vancouver

‘An unsustainable situation’

Stovell’s comments come as demolition and construction crews prepare to set in motion a level of major redevelopment work along the strip that hasn’t been seen in decades.

It begins this summer with the launch of a 10-storey, $110-million social housing project and 50,000 sq. foot health centre on city-owned land at 58 West Hastings, across from the iconic Save-On Meats.

A few blocks away at Columbia Street, another strip-altering 100-unit social housing project and “healing centre” involving B.C. Housing and Lu’ma Native Housing Society is slated to begin this year.

There is also confirmation the city-owned Balmoral Hotel could be part of a land assembly to redevelop the north side of East Hastings, near Main Street, for another large housing-health centre facility.

Other properties on the strip belong to a mix of holding companies, developers, non-profits, social service groups, Chinese family associations, Vancouver Coastal Health and a long-time barber, who is selling his two-storey building at 245 East Hastings for $1.7 million.

Owners with plans to redevelop can only proceed under the confines of the Downtown Eastside plan approved by the previous city council in 2014.

Which means no condo towers.

As the plan stands today, the housing mix of a new high-density development must adhere to a formula of at least 60 per cent social housing and 40 per cent market rental.

There is some variation of that mix west of Carrall Street that could include condos but incentives for increased heights require up to two-thirds social housing or 100 per cent market rental.

Jon Stovell, president and CEO of Reliance Properties sold the company's Burns Block building in April to the B.C. government for $10.9 million | File photo: Dan Toulgoet

Those guidelines are problematic for Stovell and others who believe home ownership, more market rental-only buildings and diverse retail businesses can benefit the neighbourhood.

When Reliance acquired the Burns Block building more than 10 years ago, it was an empty shell and in rough shape. The company spent more than $5 million on renovations to create 320 sq. foot “micro-lofts” of market housing.

The 1908-1909 era building won awards for heritage and affordability. PBS came from New York to produce a documentary on its transformation.

A beer tasting room set up on the ground floor.

“We had a really good run with the building,” Stovell said. “It always had a waiting list. A lot of people were able to formulate their first home there.”

Then, he said, a combination of street disorder and crime fuelled by an increase in homelessness and the fentanyl drug poisoning crisis caused the company to rethink its investment.

“It ended up that our tenants could not even go in and out their front door,” he said, noting police advised residents to enter their homes via the alley.

Tenants were assaulted, spat on and had to be careful of feces and needles near the building’s entrances, said Stovell, who was disappointed in the response from police and city hall.

“The police wouldn’t do anything, the city manager wouldn’t do anything and the head of engineering wouldn’t do anything,” he said. “Eventually, we realized it was an unsustainable situation.”

The company reached out to B.C. Housing, knowing it was in search of more properties in the area. The result is 30 studio units will now go to women committed to reducing or stopping substance use.

The beer tasting room will be converted to an on-site outreach program operated by Atira Women’s Resource Society, which will also manage the building.

Stovell suggested the $10.9 million B.C. Housing paid for the Burns Block could have been better spent on developing or helping acquire a greater number of social housing units outside the Downtown Eastside.

“The province paid about $1,350 a square foot for those units, which is more than a

Coal Harbour condo,” he said.

While B.C. Housing got to fulfill its mandate of providing housing for low-income vulnerable people, Stovell was disappointed his building wasn’t embraced and promoted as an example of positive change for the neighbourhood.

“You’re taking entry-level market housing and turning it back into social housing — that’s not progress,” said Stovell, whose venture in the neighbourhood got off to a rocky start when activists disrupted a news conference to open the building. “They had signs that said — and I’ll never forget this — ‘No students and young workers in the Downtown Eastside.’ Like, what’s that?”

The Arpeg Group owns the former B.C. Collateral and Loans building at 71-77 East Hastings | Photo: Rob Kruyt

‘It drove me crazy’

Drew Ratcliffe, president of the Arpeg Group, shares some of Stovell’s concerns about the state of the neighbourhood and its future direction.

The family-run company owns the former B.C. Collateral and Loans building at 71-77 East Hastings, near Columbia Street.

The building has retail space at street level and 19 apartments on the second floor that tenants — many of whom are young people and work in the service industry — pay below market rent.

The company temporarily relocated its main office to the building five years ago while waiting for its headquarters in Coal Harbour to be renovated.

Ratcliffe said the company has since moved out of the space but has no plans to sell or redevelop. When the company was on the strip, it had an architecture-design firm move in the building.

Between the two companies, they brought jobs to the area, employees spent money on dining and parking, bringing life to what was a vacant retail space.

But Ratcliffe said city hall pushed back on their presence, arguing neither company represented suitable retail use — to which Arpeg Group argued it fit the designation because anyone could walk in off the street and rent an apartment from them, which is the bulk of the company’s business.

As for the architecture firm, Ratcliffe said: “I’d have these calls from the city saying, ‘Well it’s not retail land use. So therefore we can’t give them a business licence and they’ve got to go.’ It drove me crazy.”

Ratcliffe estimated employees spent $250,000 in the area’s local economy while the companies were on the strip, including hiring Mission Possible and paying people on the street to clean their windows.

“That’s not chump change, and it’s certainly better — in my opinion — than boarding everything up,” he said, noting the street disorder coupled with garbage and human waste has returned outside the building.

Ratcliffe emphasized he never had a problem with people on the street, noting he and other staff are trained in the use of the overdose-reversing drug, Naloxone.

He said he administered the drug twice.

“I had more trouble with the city in understanding what is acceptable retail use,” he said, noting his frustration led him to survey what other street-level businesses operated in the vicinity. “There’s convenience stores selling five-dollar bowls of cereal and drugs under the counter. And then there’s a coffee store that pops up here and there. That’s about it. Everything else is boarded up.”

Like any major city, he said, Vancouver has its troubled spots but Arpeg Group wants to play a role in the strip’s revitalization, including encouraging the use of retail space in the neighbourhood for community groups and artists.

“We have no plan on developing the site, we’re committed to hopefully contributing and being part of the neighbourhood,” he said. “But it’s certainly a difficult slog when, as far as I’m concerned, the city isn’t as cooperative as one would think.”

Near the end of the interview, Ratcliffe shared that he recently secured a lease agreement with a tenant for the two retail spaces: Providence Health Care.

The Crosstown Clinic, an innovative program that provides prescription heroin to clients, will move in October from its location at Abbott and Hastings to one of the spaces; plans are still being finalized on what Providence will operate in the adjacent storefront.

“Working with Providence has been good over the last few months and I’m optimistic and think [Crosstown] is a really valuable component of helping people down there,” said Ratcliffe, who described the scene outside his building as heartbreaking.

The B.C. government purchased the Patricia Hotel and its parking lot in April for $63.8 million | Photo: Rob Kruyt

‘Positive thoughts’

It was the street disorder on the strip that led Lindsay Thomas and her brother, Daryl Nelson, to publicly call on police and city officials in the summer of 2019 to do something about it.

The siblings, whose family had owned the century-old Patricia Hotel since 1983, said the escalating mayhem outside their doors was negatively affecting business.

“There has been an increase in thefts from vehicles in our parking lot and on our property — and interactions and altercations that staff have to deal with on a regular basis have escalated to levels of violence that we have not seen before,” Nelson told the Vancouver Police Board two years ago. “This is also an issue that has unfortunately been observed and commented on regularly by the travellers that we accommodate through the year.”

Two weeks later, a dozen officers responded to the sidewalk outside the hotel and fired at least three beanbag rounds from a shotgun at an agitated man who appeared to be under the influence of drugs.

The scene, which was captured on video and shared on social media, was witnessed by tourists checking into the hotel, which is located one block from Oppenheimer Park, where a tent city operated at the time.

Fast forward to this spring and the Patricia Hotel and its adjoining parking lot are now owned by B.C. Housing, which paid $63.8 million for the property.

Dozens of its new tenants recently moved in from the Strathcona Park homeless camp. The family, however, hasn’t divested all interest in the property, having leased back the building’s popular pub and brewery for at least a year.

Thomas said the family wasn’t planning to sell the hotel but a combination of ongoing street disorder and a decrease in business related to the conditions on the street and pandemic forced the sale.

“When you start thinking about having no revenue, really, to speak of for several years in a row, then you really have to start questioning what it is that you’re doing and how you’re going to get through it,” she said, noting tourism may not return to pre-pandemic levels until next year or in 2023.

Like other longtime owners, Thomas said she wants the strip revitalized with simultaneous efforts to get people on the street the help they need.

She knows the issues are complex but said that shouldn’t stall investment that leads to boards removed from storefront windows and buildings reactivated for positive change, including market housing.

“I think that everybody who’s been there for a long time has had positive thoughts about what the neighbourhood could be, but it just never comes to fruition,” Thomas said. “It would be great if we could see more development of mixed-use buildings. At the street level, there should be more commercial. Get those doors open, get services in there, get business in there that are going to be positive additions [to the neighbourhood].”

People congregate on the Hastings strip, near Carrall Street | File photo: Dan Toulgoet

‘It’s not like nothing is happening down here’

The concerns and complaints of owners on the strip are familiar to Tom Wanklin, the city’s senior planner for the Downtown Eastside, and Shayne Ramsay, the CEO of B.C. Housing.

Both said during separate walks this month along Hastings that context is required to understand the vision for the strip and its corridor.

First, the area has always been home to low-income people and the strip has a history of cheap rental accommodations dating back decades; median income is $23,359 per annum, according to a city document from October 2020.

Second, homelessness is at an all-time high — accelerated by the pandemic — and safe, secure, affordable housing is scarce.

Third, it’s better that dilapidated, high-rent single-room-occupancy hotels be put in the hands of government and non-profit housing managers rather than unscrupulous, bylaw-breaking landlords.

Fourth, the Downtown Eastside is the epicentre of the overdose death crisis and medical clinics, healing centres and outreach services incorporated into housing is crucial to decrease the human tragedy.

Fifth, the federal government is back in the housing game and providing funding to the city and provincial government to accelerate construction and acquisition of housing.

More condos are not the answer, said Wanklin as he walked along Hastings on a sunny afternoon, where the sidewalks were filled with people as police and paramedics were active up and down the strip.

“Condos can displace,” he said. “So the vision for Hastings is redevelopment in recognition of the needs of the community and trying to have a local serving retail and service use on the ground floor.”

Wanklin wasn’t familiar with Ratcliffe’s particular case about what constituted suitable retail use on the strip. But he noted amendments were made in January to the city’s retail continuity bylaw to allow more flexibility of storefront spaces.

Hastings Street requires properties to be retail on the ground floor. But Wanklin said owners have complained that they can’t find tenants.

The amendments to the bylaw now allow an owner to apply for an exemption for various uses to storefronts, including general office, healthcare, social services, cultural, recreational, economic development, training and education.

So could an architect set up shop?

“Yes, that would fall into ‘general office,’” he said.

Graphic created by Robert Huynh with data from Jeremy Hainsworth

While Glacier Media’s focus of this story was the Hastings strip, both Wanklin and Ramsay pointed to increases in housing and services in the wider neighbourhood as evidence positive change is happening.

Wanklin produced a map of the Downtown Eastside covered in small red dots, marking condominium, social housing and market rental projects in development or completed since 2014.

The map included the Hastings strip, Gastown, the Oppenheimer Park neighbourhood, Chinatown, Strathcona, Victory Square, Thornton Park and the industrial area near the waterfront.

Totals for condos: 368

Social housing: 1,791

Market rental: 763

In addition, close to $10 million in grants were given to various agencies in the neighbourhood over the past six years, Wanklin said.

“It’s not like nothing is happening down here,” he said. “But it’s not obvious to a lot of people because of this sort of centrality of real human tragedy that they witness on a daily basis.”

B.C. Housing CEO Shayne Ramsay on Hastings Street across from former Only Cafe building, which will soon be demolished | Photo: Mike Howell

‘Making sure that folks aren’t pushed out’

Ramsay picked up on Wanklin’s point as he stood on a sidewalk at Gore and East Hastings on a recent morning.

He mentioned a mixed-used housing development in Blood Alley in Gastown and redevelopments of the Union Gospel Mission on East Cordova and Roddan Lodge at Dunlevy and Alexander.

“That’s well over 300 units of housing,” Ramsay said.

As for the type of housing, Ramsay said: “What’s wrong with purpose-built rental?” He pointed across the street to a highrise at 288 East Hastings that has a mix of non-market and market rental housing.

Further down the strip at 41 East Hastings is the Olivia Skye building that also offers a mix of housing for people, including those paying welfare rates and others spending more than $1,500 per month for a one-bedroom.

“It’s important to provide a range of housing, but making sure that folks aren’t pushed out and areas gentrified,” he said, pointing to community pushback over condo towers recently built in Chinatown.

Ramsay believes taxpayers are getting good value for the investments in the neighbourhood, noting the $10.9 million price for Stovell’s Burns Block building was justified.

“Burns Block was a good acquisition from the point of view that it was a good restoration and we turned it back to the community,” he said, as he walked by the six-storey building. “We couldn't build that number of units [30] for the acquisition cost.”

Investments in the neighbourhood haven’t just been in real estate, said Ramsay, noting the creation in 2017 of B.C. Housing’s Community Impact Real Estate Society, or CIRES.

The non-profit society manages B.C. Housing’s commercial spaces, including the ground floor across the street at the highrise at 288 East Hastings, where the Potluck Café Society will relocate.

An example of the society’s function saw CIRES provide retail space to East Van Roasters at a reduced rent in the B.C. Housing-owned Rainier Hotel in Gastown, which in turn allowed the business to invest in training and hire women from the Downtown Eastside.

But what about the street disorder?

Its prevalence is an indication to Ramsay that not enough housing is available to bring people inside and get them stabilized.

He supports a partnership with the city and the federal government to develop a strategy to acquire private single-room-occupancy hotels, many of which are poorly managed and charge high rents.

“It’s terrible housing for folks,” he said.

An example of such housing existed for years at the Sahota family-run Balmoral and Regent hotels, which now sit vacant until the city and B.C. Housing develop a plan for the buildings’ future.

The city acquired both hotels in December 2020 for an undisclosed sum, although the Sahotas’ lawyer told city council in 2019 that private offers ranged for $7 million to $12.5 million for each building. (Glacier Media filed a request for the agreement in December under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act; the city said it may take until October to respond).

Ramsay said the Regent is expected to be turned into self-contained suites while the Balmoral may be part of a land assembly purchase to develop a large housing and health centre.

Such a real estate move would mean buying at least two properties from Concord Pacific, another property belonging to the Sahota family, a building that houses the Insite injection site, a cannabis dispensary and a few other buildings.

Developer Peter Wall of Wall Financial, who declined an interview for this story, has proposed the city and province work with him to build at least 168 units of housing, a medical centre, injection site and treatment rooms on the properties.

“We’re going to have discussions with Wall if the private sector is interested in looking at being part of an assembly and redevelopment,” Ramsay said. “It may not be something like [Wall’s proposal], but the assembly around the Balmoral with the redevelopment of that strip makes a lot of sense. But what you put there is still up for discussion.”

The Sequel 138 condo project is on the site of the former Pantages Theatre and adjacent to the Regent Hotel. Photo Rob Kruyt

‘It’s so ironic’

Across the street from the Balmoral is the type of housing project that will likely never get built again on the strip.

The Sequel 138 housing complex, which required the demolition of the old Pantages Theatre, was constructed when the city still allowed condo developments in the area.

The six-storey building is a mix of small 79 private condos and 18 rental units. In 2015, the going price for the condos ranged from $250,000 to $394,000.

At the time, B.C. Housing provided a $21.8 million loan to developer Marc Williams. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation also provided a down payment program to help young buyers whose household income was no more than $85,000 a year.

Like Stovell’s foray into providing a different mix of housing along the strip, Sequel 138 was also met with pushback from housing activists.

“The reason why everybody struggled so hard against the Sequel project, and struggled for 100 per cent social housing, is that it will have a displacement impact because the land around it becomes more valuable,” Wendy Pedersen, a community activist, told the Vancouver Courier in 2015. “It’s not going to help the people in the Regent and the Balmoral live a better life.”

The realtor attached to Sequel 138 was Anthony Kuschak, who has watched the street disorder grow outside the building, which is adjacent to the Regent.

Statistics posted on the Vancouver Police Department’s website in April 2018 showed officers responded to 845 calls in and outside the Regent between Jan. 1, 2017 and Feb. 22, 2018.

More than 50 categories of calls involved crime related to assaults, fights, drugs, weapons, robbery, theft and extortion.

Kuschak has also watched more social housing get built.

“The only kind of building that happens in the Downtown Eastside now is government-funded social housing through B.C. Housing,” he said. “And that’s because developers can’t make it work [with restrictions on what can be built].”

He, too, lamented the fact the strip is lacking diverse retail.

“Tim Hortons won’t go there, 7-11 won’t go there — no one will go there,” Kuschak said. “You’ve got these ragtag, pop-up convenience stores. They go to Costco, then sell you toilet paper for two bucks a roll. It’s so ironic.

The Garlane Pharmacy near Main and Hastings has operated for 40 years | Photo: Rob Kruyt

‘A different ball game now’

Watching the strip change for better or worse over the past 40 years has been pharmacist Gary Siu, co-owner of Garlane Pharmacy at 232 East Hastings.

The pharmacy’s customers are largely people from the street and single-room-occupancy hotels who require medication to help them fight their addictions.

Ironically, the pharmacy’s location is the former home of a liquor store that Siu said closed over concerns regarding alcohol abuse in the neighbourhood.

Unlike other businesses negatively affected by pandemic restrictions, Siu said there’s been no change in business over the last year. The street disorder hasn’t affected business, either.

“People need to eat and people need medicine,” he said, noting he and his staff recently provided the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine to customers.

A self-described “east side kid” who attended Strathcona elementary and graduated from Britannia secondary in the 1970s, Siu said homelessness and drug addiction is the worst he’s seen in his career.

“It was much cleaner — you didn’t see people sleeping in the streets and so on,” he said, when asked about the pharmacy’s early days on the street. “It’s a different ball game now.”

He picked up on a popular conversation piece regarding homelessness and wondered how many people facing challenges in the neighbourhood are originally from Vancouver or other parts of the province.

Siu said he empathizes with his customers, many of whom he knows on a first-name basis. They may have taken a wrong path, or had a difficult childhood, he said.

“Their way of thinking may be different than mine, but 99 per cent of my customers are nice,” he said. “The occasional one comes in here and thinks they’re king of the hill.”

He is aware of some of the investments on the strip from B.C. Housing and the City of Vancouver to provide housing for people like his customers.

Siu said it seems like the right thing to do — including government leasing the shuttered Army & Navy store for a shelter — but questioned how much more money needs to be spent in the neighbourhood.

“When will it be enough?” he said, suggesting one person who gets off the street is usually replaced by another person in distress. “It’s a very complex situation, but if nobody gives a damn, then it will be chaos. It’s hard to find a solution.”

Jacqui Cohen announced in May 2020 that her family's Army and Navy stores were closing for good | File photo: Chung Chow

Army & Navy shelter

Whether the Army & Navy property at 15-27 West Hastings becomes part of that solution in terms of permanent housing and social services is not something owner Jacqui Cohen wanted to discuss when reached last week.

Cohen announced in May 2020 that her family’s iconic discount department store on West Hastings and four others in B.C. and Alberta would close for good after more than a century in business.

“My Grandpa Sam would be very proud, as am I, to have our family’s Army & Navy building used to temporarily support 60 of our city’s most vulnerable individuals,” Cohen told Glacier Media in an email. “Army & Navy was a community constant for 101 years. When I made the difficult decision last year to close our operations due to the insurmountable challenges of COVID, I knew I wanted the future of the buildings to be of benefit to the communities. Using the Hastings store for temporary shelter is good for the Downtown Eastside, and that is the current focus.”

Meanwhile, there is great anticipation from the community about the imminent launch of the 10-storey, $110-million social housing project at 58 West Hastings, which is on the same block as Army & Navy.

The site, which is nearly the size of a football field and once served as a homeless camp and community garden, will see the construction of 230 new homes alongside a 50,000 sq. foot health centre.

Homes will be a mix of micro, studio, one-bedroom and two-bedrooms, with 120 rented at the welfare rate and 110 at subsidized rates via B.C. Housing’s housing income limits formula.

The project brings together the Vancouver Chinatown Foundation, which raised almost $30 million for the project, and the provincial and federal governments.

The city acquired the land in 2014 in an agreement with Concord Pacific.

Carol Lee of the Vancouver Chinatown Foundation believes the project will be good for the neighbourhood and provide much-needed health services for residents.

“We’re excited about it and hope that it is going to be a positive contribution,” said Lee, who has worked 10 years on securing funding for the project.

Doors are expected to open in spring 2024.

Mayor Kennedy Stewart on Hastings, near Gore Street | Photo: Rob Kruyt

‘Healing corridor’

Mayor Kennedy Stewart will join Lee at the launch of the project, which was originally set for May 27 but will now likely go ahead this summer.

David Eby, the provincial minister responsible for housing, is expected to participate.

So is his federal counterpart, Ahmed Hussen, who has been a familiar [virtual] presence in B.C. in recent months to announce funding for housing in Vancouver and other parts of the region.

Stewart, who was elected in 2018, follows a succession of mayors over the past two decades who made various commitments to help the city’s most vulnerable.

In Larry Campbell’s 2002 inauguration speech, he said “if we do our work well, we should be able to eliminate the open drug market on the Downtown Eastside by the next election.”

Campbell was replaced by Sam Sullivan in 2005 and over his three-year term promoted a drug treatment initiative and a plan to reduce homelessness and street disorder by 50 per cent by 2010.

Then Gregor Robertson had a 10-year run at city hall and promised to end “street homelessness” by 2015.

Vancouverites know the mayors’ efforts, although good intentioned, didn’t make for transformative change, with overdose deaths and homelessness currently at all-time highs — a reality prior to the pandemic’s worsening of the crises.

Stewart is now focused on his campaign to decriminalize simple possession of illicit drugs while working to build more affordable housing across the city, including in the Downtown Eastside.

As for the Hastings strip, the conversations he’s had with community members point to a strong interest in developing a “healing corridor” that recognizes the trauma and suffering of area residents, many of whom are Indigenous.

“Which I think is a really good idea,” Stewart said by telephone last week.

As an example of such a concept, the mayor pointed to a large-scale development expected to begin construction this year on the south side of East Hastings at Columbia Street, where the Pigeon Park Savings building, public street market and Shaldon Hotel exist.

The Indigenous-led project, which involves the Aboriginal Land Trust, Vancouver Native Health Society and Lu’ma Native Housing Society, means those properties — owned by B.C. Housing — will be cleared to build more than 100 units of supportive housing and affordable rental apartments.

The new building will feature a healing centre that can be accessed by a mix of tenants including urban Indigenous families, Downtown Eastside residents and other low-income people.

“This really should be our objective — to have a community-driven re-envisioning of what we can do along [Hastings],” Stewart said. “And this is possible because senior partners [in government] have come on board with quite a lot of enthusiasm, which has been absent for many, many years.”

The wider conversation of what is allowed to be built up and down the strip had the mayor refer to what’s happening to older neighbourhoods in American cities.

“In so many city centres around the world, [the Hastings strip] would be prime targets for speculators and investors who would buy cheap property, tear it all down and build luxury stuff,” he said. “Gentrification is not the answer here.”

***Glacier Media reporters Jeremy Hainsworth and Graeme Wood contributed extensive research for this report, including dozens of online property searches, accessing public records and data collection. Robert Huynh created the interactive map of properties.