The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its sixth assessment today, and while it points to ever improving observational data and modelling that gives scientists higher degrees of confidence in predicting possible impacts, the most significant thing about the report is its timing.

It was released at a moment when observable extreme weather events – heat waves, drought and flooding – are occurring around the globe, including Canada, where a record heat wave has helped to trigger widespread wildfires.

Since 1990, the IPCC – a United Nations body that coordinates hundreds of scientific studies on climate change into periodic assessments -- has released major assessments every six or seven years.

There are three different working groups. Today’s report is the work of Working Group 1, which deals with the physical science of climate change. The Working Group 3 report – which deals with mitigation – is due in March 2022.

The Sixth Assessment (AR6) of Working Group 1 report points to human-caused warming of 1.1 degrees Celsius since the period of 1850 to 1900. While other greenhouse gases, like methane, contribute to global warming, the IPCC notes that CO2 is “the main driver.”

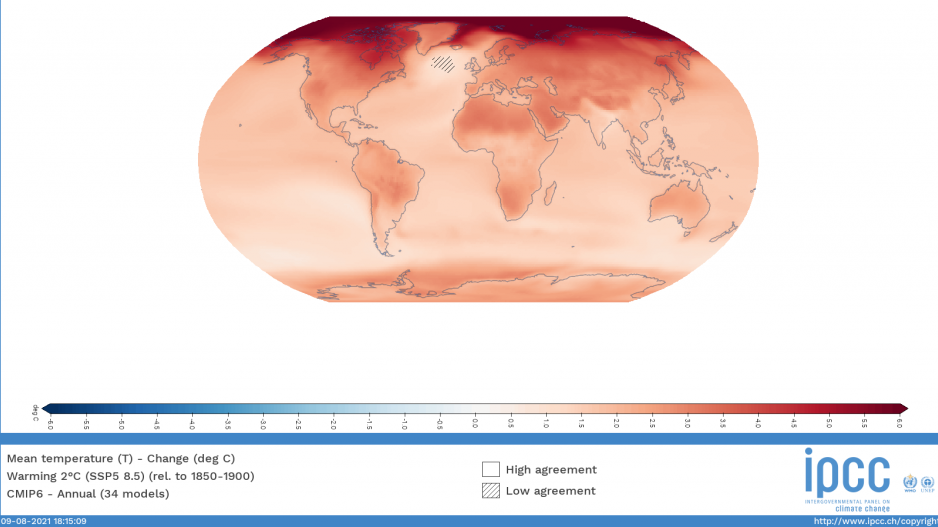

Warming of 1.5 to 2 degrees C is the point where significant impacts can be expected – greater melting of icecaps and glaciers, increasing sea level rises, increased ocean acidification and more extreme weather events.

The AR6 report moves up the timeline for crossing the 1.5 C threshold to the 2030s, about a decade earlier than previous estimates.

“The report provides new estimates of the chances of crossing the global warming level of 1.5°C in the next decades, and finds that unless there are immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, limiting warming to close to 1.5°C or even 2°C will be beyond reach,” the IPCC warns.

“For 1.5°C of global warming, there will be increasing heat waves, longer warm seasons and shorter cold seasons. At 2°C of global warming, heat extremes would more often reach critical tolerance thresholds for agriculture and health.”

The IPCC notes that the science, modelling and observational data continue to be refined with each assessment. The AR6 includes improved observational data, as well as a better understanding of climate sensitivity (how the climate responds to increased levels of greenhouse gases.)

Zeke Hausfather, director of climate and energy at the Breakthrough Institute, noted on Twitter that there is good news and bad news in the AR6 report, in terms of refining climate sensitivity models.

“The bad news is we are much less likely to get lucky and have climate change on the milder side of what we expected,” he wrote. “This sensitivity revision cuts the legs off the lukewarmer argument.

“The good news is that it suggests that very high sensitivity outcomes of 5C+ as is found in some of the new CMIP6 (coupled model intercomparision projects) models is very unlikely.”

“This report is a reality check,” said IPCC Working Group I co-chairperson Valérie Masson-Delmotte. “We now have a much clearer picture of the past, present and future climate, which is essential for understanding where we are headed, what can be done, and how we can prepare.”

A “pause” in warming that occurred between 1998 and 2012 – i.e. warming that occurred slower than modelling predicted – was a “temporary” event, the AR6 finds, with average warming resuming and accelerating since then.

“There is now very high confidence that the slower rate of global surface temperature increase observed over this period was a temporary event," the report notes.

“Since 2012, strong warming has been observed, with the past five years (2016–2020) being the hottest five-year period in the instrumental record since at least 1850.”

Whereas the previous report estimated crossing the 1.5 C threshold would “likely” occur between 2030 and 2052, AR6 moves the timelines up by a decade, “assuming no major volcanic eruptions.” (Large volcanic eruptions put so much dust into the atmosphere that it can result in temporary global cooling.)

While the world would have experienced a sharp dip in CO2 emissions in 2020, due to the global pandemic, which drastically reduced the use of fossil fuels, it is a blip that will have no measurable long-term impact.

“Temporary emission reductions in 2020 associated with COVID-19 containment led to small and positive net radiative effect (warming influence),” the IPCC states. “However, global and regional climate responses to this forcing are undetectable above internal climate variability due to the temporary nature of emission reductions.”

The report notes that global warming intensifies water cycles, something that is already being experienced in some parts of the world, with more precipitation in the winters, and drier, earlier summers.

“This brings more intense rainfall and associated flooding, as well as more intense drought in many regions,” the IPCC says in a news release.

It also increases the frequency of coastal flooding: “Extreme sea level events that previously occurred once in 100 years could happen every year by the end of this century.”

In the oceans, warming will lead to greater acidification and reduced oxygen, which will have an impact on marine life. B.C. is likely already seeing the impacts of this in the form declining wild salmon stocks. A number of fisheries scientists have said they believe climate change to be a major contributing factor in declining wild salmon stocks in the more southern ranges.

“Changes to the ocean, including warming, more frequent marine heatwaves, ocean acidification, and reduced oxygen levels have been clearly linked to human influence,” the IPCC states. “These changes affect both ocean ecosystems and the people that rely on them, and they will continue throughout at least the rest of this century.”

John Clague, professor of Earth Sciences at Simon Fraser University, said the report underscores that the warming is "locked in," due to the persistancde in the atmopshere of CO2. So now matter how quickly nationas are able to respond to reducing GHGs, it won't stop the warming already underway.

"We are going to have to adapt to the consequences of this, which include at least 50 cm of sea-level rise by the end of this century and more of the type and intensity of weather events we’ve seen this year (wildfires, floods)," he wrote.

Andrew Weaver, climate scientist at the University of Victoria and former Green Party leader, said the sixth assessment is really just "more of the same, greater certainty."

"The reality is we don't need another one of these reports to tell us that we have problems and that we need to deal with them," he said.

Chris Bataille, a Simon Fraser University researcher, who is contributing to upcoming Working Group 2 and 3 assessments, notes that the AR6 report is “unequivocal” that human activity is contributing to global warming and that some of the impacts will be “irreversible” for centuries.

Muting the impacts of global warming will require rapidly decreasing GHGs and moving to net zero CO2 emissions.

In an email to BIV News, in response to the AR6 assessment, Bataille said “if we can get CO2 and then GHGs to net-zero by the 2050-70 range, we can maybe hold the line at (2 degrees C) and then start repairing the damage.”

Editor's note: This story has been updated with additional comments from scientists.